Shanghai port is the busiest in the world. Activity there is closely monitored by financial analysts distrustful of official statistics and looking for clues as to what is really happening in the world’s second-largest economy. For the past few days they will have been taken for a wild ride.

First there was mayhem as ships rushed to load up with containers, half of them destined for the United States, in an effort to beat tariff deadlines. By this weekend the place is reportedly at a near standstill. “Containers that missed the narrow window now sit idle in stacks along the docks. Many shippers are either pulling cargo back or scrambling for alternatives,” according to the Chinese business magazine Caixin.

After a dizzying series of tit-for-tat increases, accumulated US tariffs on Chinese goods now stand at 145 percent, while China has imposed 125 percent on American imports. After its latest hike on Friday, Beijing suggested that it would be the last because at those levels it had effectively killed trade and there was no point in going higher. “Given that US exports to China are no longer commercially viable under the current tariff levels, if the US continues to raise tariffs on Chinese exports to the US, China will no longer respond,” the Customs Tariff Commission of the State Council said on its website. A Commerce Ministry spokesperson accused Washington of “weaponizing and politicizing tariffs to engage in bullying and coercion,” calling the tactics a “joke.”

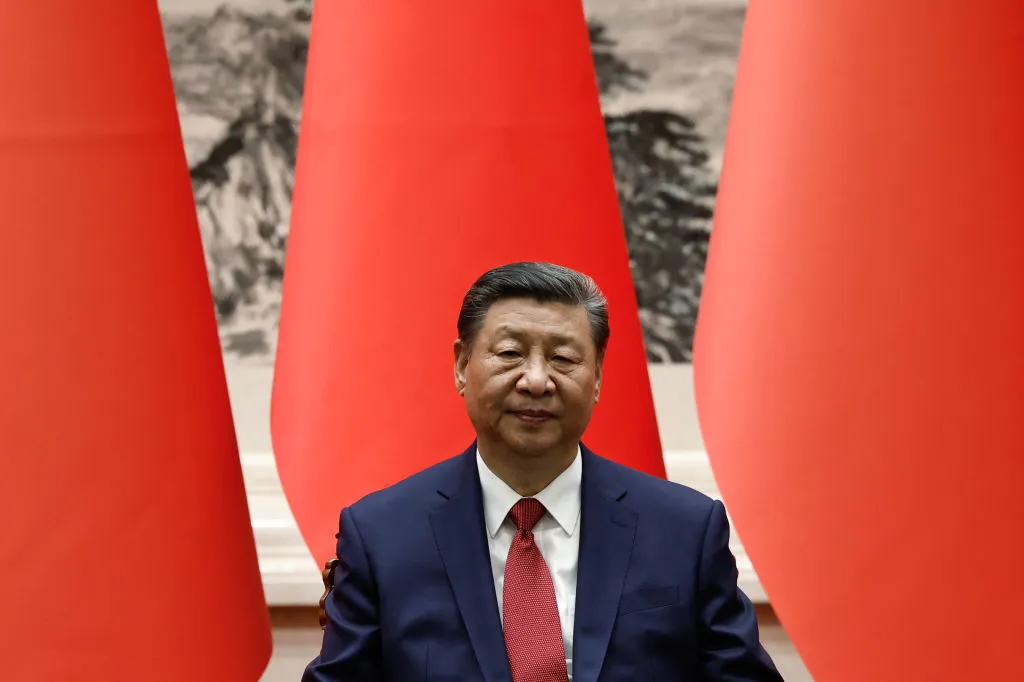

As Shanghai port was grinding to a halt, Xi Jinping was hosting Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez in Beijing, telling him that “unity and cooperation” were needed by the rest of the world. He will take much the same message to Vietnam, Malaysia and Cambodia next week, urging them to stand together with China in face of the Trump wrecking ball and embrace a “shared [that is, a Chinese] future.” Chinese state media is presenting Xi as a champion of free trade and globalization and pushing the need for “coalition building” against Trump.

It is now clear that Beijing is not about to fold and is set on extracting maximum diplomatic advantage from the escalating trade war. Beijing’s accusations of “coercion,” “bullying” and “rule-breaking” against the US are of course breathtaking hypocrisy, since all three have been central to China’s rise. But Xi will be calculating that his blandishments will still be welcomed by a world shell-shocked by a rampant American president, who is alienating friends and foes alike.

He also needs markets for a tidal wave of cheap Chinese exports redirected from the US, the world’s biggest consumer market, and needs Southeast Asia in particular to turn a blind eye to transshipments of Chinese goods, which often adds up to little more than relabeling the products as made elsewhere. Supply chains are complicated – often a single product (an iPhone, for instance) has components from multiple sources – and Chinese logistics firms were very adept at ducking, diving, and weaving around trade restrictions well before the latest hostilities. Those dark arts will now come into their own.

While Xi has drawn a line under further tariff increases, he has a toolbox of other coercive measures waiting in the wings. For Trump, tariff is the “most beautiful word,” but the Chinese Communist party has a whole vocabulary of bullying, built over decades of forcing foreign firms and pliant countries to kowtow as a price of doing business or to punish them for supposed sleights against China. There was a hint of this on Friday, when Beijing announced it would further restrict the number of US movies allowed to be screened in China. There is already a cap, and Hollywood has prostrated itself disgracefully in front of CCP censors with China-friendly scripts in order to gain entry. In the bigger scheme of things the latest restrictions will have limited economic impact, but their usefulness for Beijing lies in being a high-profile hit to a major US cultural export.

Other weapons in China’s coercive toolkit include targeted boycotts of US firms or goods, as already witnessed against clothing firms which have criticized the use of forced labor in Xinjiang’s cotton fields. Beijing may also step up regulatory investigations on spurious grounds, such as tax evasion, anti-trust or data security. Google and DuPont are already facing investigations for unspecified monopolistic behavior. A nightmare for foreign firms is hostage diplomacy, at which China is becoming increasingly adept. Under Xi there has been a worrying rise in exit bans, whereby foreign executives engaged in business disputes, real or imagined, are barred from leaving the country.

Beijing could abandon its modest cooperation on the flow of precursor chemicals that have helped fuel America’s fentanyl crisis, and the laundering of the proceeds, where Chinese banks have been implicated. It could target US service companies, law firms, and banks, for instance, where America enjoys a trade surplus with China. Watch out too for stepped-up pressure on US companies, desperate to stay in Xi’s good books, to hand over intellectual property. Further restrictions on key exports on which the US is highly dependent, such as critical minerals used in the technology and defense industries, could come too.

Beijing could also manipulate its exchange rate to make its exports cheaper and dump Treasury bonds. China is the second-largest holder of US debt after Japan and there has already been speculation – without hard evidence – that this week’s wild swings in the US bond markets were provoked by Chinese selling.

That turbulence, the largest surge in 30-year yields since the pandemic, appears to have been the reason why Trump blinked, pausing higher tariffs against the rest of the world (though they still have a minimum 10 percent), while further hiking them against China. This was presented by some of his team as all part of a clever plan, with China the real target all along, though that seems unlikely.

Whatever the reason, the climbdown will have encouraged Beijing’s view that it can hold out longer than America. Financial analysts (when not panicking about the markets) have excelled themselves this week with analogies ranging from two prizefighters in the ring to a pair of gunslingers at high noon, and even two racing cars speeding toward each other in a deranged game of chicken. On paper at least the Chinese economy is fragile, still suffering from a property collapse, with heavy debts and tumbling inward investment. In the absence of meaningful economic reform, Xi has been counting on cheap exports to revive the economy.

It appears more vulnerable than the US. Yet China is also an autocracy, and its pain threshold is higher. It can impose more suffering on its people, and Xi is gambling that with higher inflation, job losses, and other economic dislocation from the trade war, it is Trump who will face earlier and greater political and popular pressure to change course. The US is also a far more open economy than China, and as the bond market convulsions showed this week, it is much more exposed to market sentiments, however dismissive Trump has been of gyrations in the stock market.

While it is true that the CCP depends on its economic stewardship for legitimacy – performance legitimacy as it is often called – things would have to get a lot worse to provoke the sort of popular protests seen toward the end of China’s draconian COVID lockdowns, which forced Xi to abandon his stubborn COVID-zero policy. The Party is also resorting to a familiar tactic of whipping up nationalist sentiment, presenting the trade war with America as a patriotic struggle. This week the Foreign Ministry circulated a video of a famous 1953 speech by Mao about resolve in the Korean War against America. More jingoistic movies from that era seem sure to follow, as happened during 2019 trade tensions.

Chinese social media, where “patriotic” voices are usually given more room, has been full of viral and often racist AI-generated videos about Americans. Some have depicted overweight, sweaty and downcast American workers stitching together garments on miserable production lines in a post-tariff world, where such tasks are no longer outsourced overseas. Beijing’s warning that “China will fight to the end” has become a popular social media rallying point.

Separating the European Union from America is a longstanding goal of CCP policy, and Xi will have been encouraged by the visit from Spanish Prime Minister. Sánchez, rarely one to stand up to autocrats, appeared happy to encourage this, saying he is in favor of “more balanced relations between the European Union and China.” Others will be more cautious. China’s support for Russia’s aggression in Ukraine casts a long shadow over EU-China relations, and these will not have been helped by the capture of two Chinese soldiers fighting for Russia. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky claims at least 155 Chinese citizens have joined Russia’s army, and while they appear to be mercenaries, there has been no clear explanation from Beijing.

Also buried under all the tariff noise this week was news that Xi has purged He Weidong, the number two general in the People’s Liberation Army. That follows the removal of a swath of other top military and defense officials – including two successive defense ministers. That suggests all is not well in the court of Xi Jinping, and his relationship with the army may be strained. Trump’s tariffs have given him a rallying point. Ten days after “Liberation Day,” whether by accident or design the battle has abruptly changed from Trump versus the world to Trump versus China. It is early days, but Xi so far is having a better trade war than many expected – though that may be more the result of the global chaos and confusion unleashed by an erratic Trump rather than anything done by Xi.

Leave a Reply