‘Honour,’ the French poet Nicholas Boileau wrote in 1666, ‘is like a rocky island without a landing place; once we leave it, we can’t get back.’ Especially, Donald Trump might add, when the outlook is Stormy. But Trump’s concept of honour is perhaps closer to that of Stormy Daniels’ fellow artist and near-namesake, the Elizabethan poet Samuel Daniel, who in 1592 called honour an ‘empty sound’, an ‘idle name of wind’.

These early modern attitudes still define how we think about honour. Either it’s a unique defence against life’s ethical challenges, or it’s an instrument, a luxury—an affectation that is, as Trump is alleged to have found Stormy Daniels, desirable but negotiable. In the former case, we tend to call honour ‘integrity’ or ‘self-respect’. In the latter, we tend to be less interested in retaining respect for ourselves than in obtaining ‘respect’ from others. This is the form that honour takes among thieves.

The American founders chose integrity over instrumentality. Or rather, as Craig Bruce Smith argues in his fascinating American Honor, the founders saw that integrity was instrumental in building an ethical democracy. ‘A general Dissolution of Principles & Manners will more surely overthrow the Liberties of America than the whole Force of the Common Enemy,’ Samuel Adams wrote to James Warren in 1779. ‘While the people are virtuous, they cannot be subdued.’ The Americans, Smith shows, had inherited European concepts of ‘aristocratic honor’—of honor as a hereditary trait of the ruling class. The Revolution reformulated them into ‘egalitarian honour’ or ‘democratised honour’.

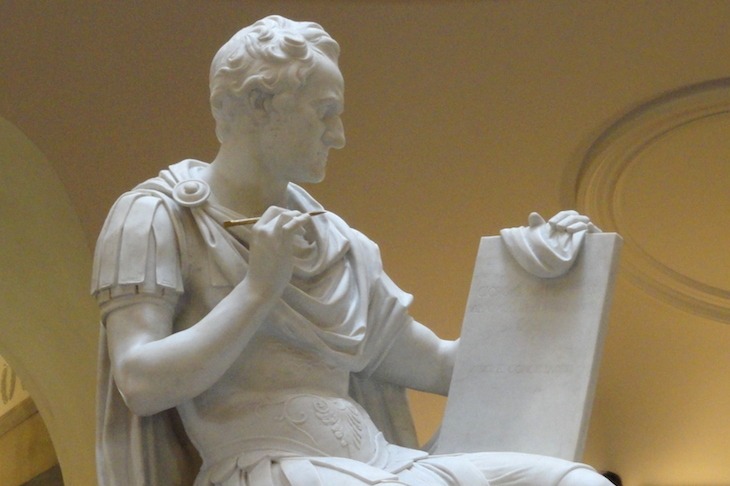

The image of democratised honour is on show this week at the Frick Collection in New York City. In 1816, the North Carolina Senate decided to install a full-length statue of George Washington in the State House at Raleigh, and asked Thomas Jefferson’s thoughts on who should get the commission. Jefferson recommended the Roman sculptor Antonio Canova, and suggested that Washington, the Cincinnatus of the American Revolution, should be shown in Roman garb, drafting his farewell address to the States.

The finished statue was destroyed by fire in 1831, and a replica installed in 1970. The Frick is showing Canova’s full-size preparatory plaster model, in which Washington is naked. ‘Did anybody ever see Washington naked!,’ Nathaniel Hawthorne asked in 1858. ‘It is inconceivable. He had no nakedness, but, I imagine, was born with clothes on and his hair powdered, and made a stately bow on his first appearance in the world. His costume, at all events, was a part of his character.’

Which brings us to the question of whether Stormy Daniels, whose costumes are always part of her character, saw Trump naked, and the ongoing spectacle of honour de-democratised. Michael Cohen insisted that he was being honourable when he paid hush money to Stormy Daniels, whose costume is part of her character. Trump, Cohen claimed, didn’t know about the transaction. Last month, Trump denied knowing anything it, just as he has denied having had sex with Daniels. This month, Trump has said that Cohen ‘represented’ him in ‘this crazy Stormy Daniels deal, as in other unspecified matters. Last week, Rudy Giuliani, in his first appearance as Trump’s lawyer, said that Trump ‘didn’t know about the specifics’ of the payment to Daniels, but that Trump ‘did know about the general arrangement that Michael would take care of things like this’, and that Trump had reimbursed Cohen for taking care of it.

We recognise the language of ‘taking care’ of ‘this thing’ or ‘that thing’ from Mafia movies. It is the evasiveness of people who expect to end up in court, sooner or later. Trump’s rejoinder to Giuliani’s account—‘He’ll get his facts straight’—has a similar cinematic quality. But the plot is utterly inconceivable. The straight facts to which we are supposed to subscribe are that Trump knew nothing about a payment about something which never happened. No one in this story is acting honourably.

I happened to be reading Craig Smith’s lucid account of the American revolution in honour as this latest involution of honour played out. Of course, honour, like Canova’s statue of Washington, is an ethical idealisation. Politics is an instrumental business, and protestations of honour easily become the penultimate refuge of the scoundrel. ‘Brutus is an honourable man,’ Mark Antony says in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, as he incites the mob to riot against Caesar’s assassins, and open Antony’s path to the imperial throne. As Smith shows, the decades after the American Revolution saw a ‘counter-revolution in American ethics’. Without a common enemy, collective ideals of honour succumbed to partisanship. Politicians resolved personal insult like aristocratic Europeans, by duelling, a habit not previously popular with Americans.

Still, democratised honour survives in American society. Travel anywhere in the United States, and especially outside the big coastal cities, and you’ll find that most Americans are courteous, egalitarian and trusting, and hence trustworthy. Look at the upper echelons of public life, however, and it’s the opposite. The Founders turned the aristocratic ideal of honour into a democratic habit. The entrenched, quasi-aristocratic class that runs the United States has ditched that democratic habit, along with the ethics that went with it. They have cast off from the ‘rocky island’ that Nicholas Boileau described, and without a moral compass. As Mark Antony says in Antony and Cleopatra: ‘If I lose mine honour, I lose myself.’