Irish folklore spoke of many worlds. There was the world of fields and hearths and then there were the hidden places where the non-material lived: the Sídhe mounds, the sea-realm of Manannán mac Lir, the land of youth called Tír na nÓg and, finally, the land of the dead. These worlds coexisted with ours. A woman might leave butter on the windowsill, lest the fairies sour the churn. A new mother would avoid complimenting her baby – at least, not too loudly – for fear he would be kidnapped by the Good Neighbors and replaced with a changeling. My first real boyfriend’s father blamed every family misfortune on their decision to cut down a hawthorn tree. This hard man who had survived the Troubles, who had survived Long Kesh, believed – even if he only believed a little bit – that his family’s suffering might have stemmed from that violation of the boundary between worlds. And he – as folklore had long advised – would never say the f-word, to avoid bringing undue attention to himself. It was always “the Little People,” “the Good Neighbors,” “themselves.”

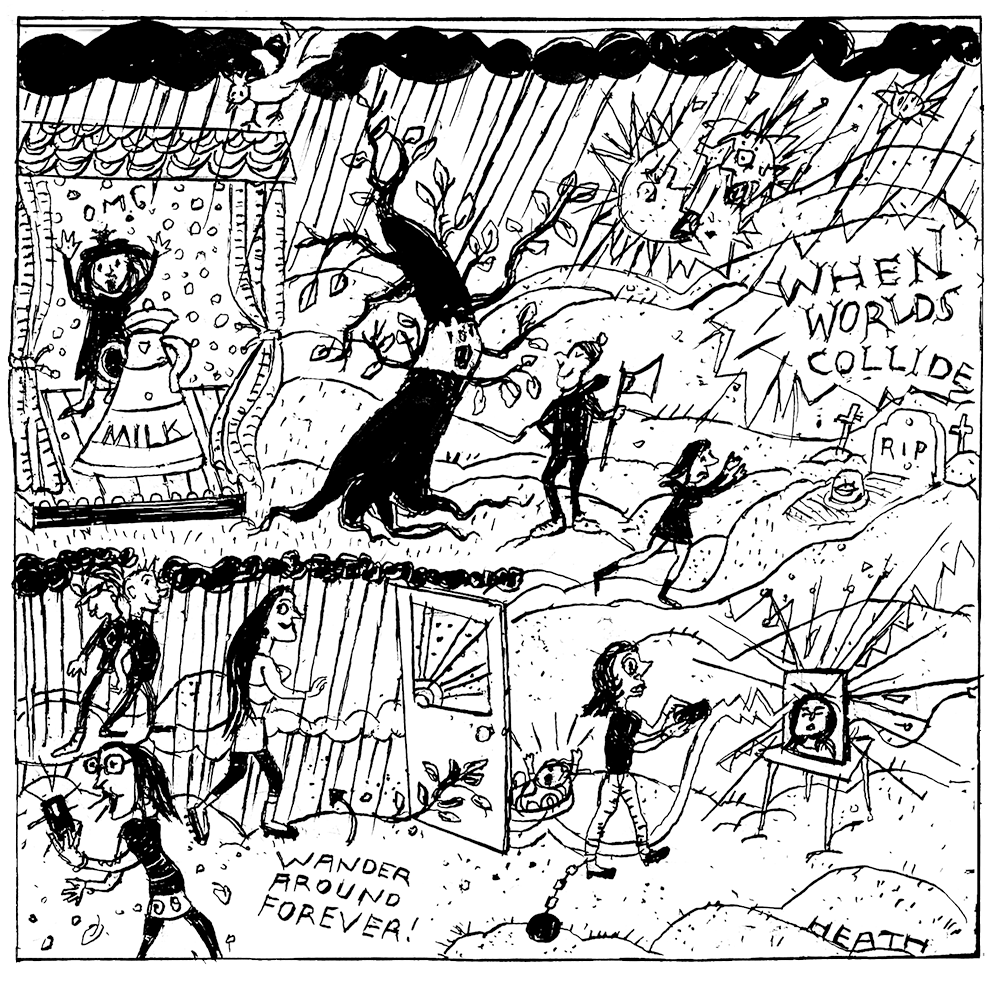

When we open our phones without purpose, hours pass unnoticed and the body is ignored until we surface, dazed

At the turn of the 20th century, W.B. Yeats and Walter Evans-Wentz both collected stories from Irish peasants about the fairy faith. Around the same time, Theosophists in London were mapping their own invisible worlds through seven ascending planes of existence: the Physical, Astral, Mental, Buddhic, Nirvanic, Monadic and Divine. The astral, second from the bottom, mattered most for human experience. It was imagined as the liminal zone just beyond the physical – close enough to reach, yet strange enough to disorient. C.W. Leadbeater’s The Astral Plane (1895) catalogued this realm where time contracts, every emotion takes visible form and unwary travelers may be deceived or vampirized by entities that defy human language.

When you set folklore’s otherworlds alongside Theosophy’s planes, they resolve into a shared idea: a zone layered over ordinary life, accessible in altered states or by accident and governed by rules that shift without warning.

The internet replicates these conditions. Our bodies stay in one place while attention goes elsewhere; time distorts so that a “quick check” expands into hours while yesterday’s news already feels remote. Identities loosen until you can be anyone, no one, or several people at once.

Like fairyland and the astral plane, the online world is navigable only if you learn its rules, which are as follows.

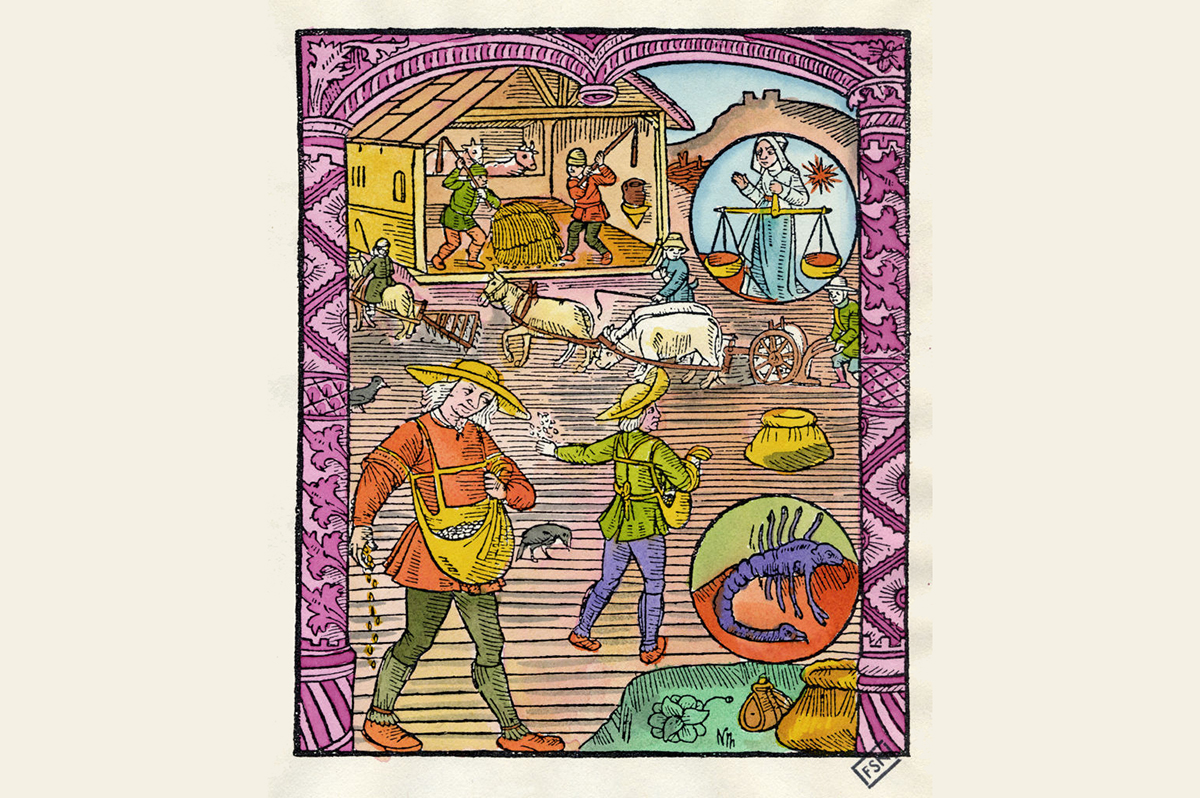

Set your intentions and ground yourself. Both occultists practicing astral travel and folklore describing journeys to Fairyland insist on the same first step: ground yourself in the physical world, then set your intention for entering the otherworld. Folklore is filled with protective anchors: iron to break enchantments, a thread to guide you home, a crust of bread to tether the body. Without such safeguards, wanderers risk vanishing forever – or returning to find that years have passed while they thought they’d only lost an hour.

We violate this rule constantly when we open our phones without purpose, slipping into a trance. Hours pass unnoticed; the body is ignored – hunger, thirst suspended – until we surface, dazed, with little memory of how we spent the time or why.

The antidote is grounding. Modern equivalents of old superstitions might be alarms, leaving phones to charge in another room or returning to analog clocks. Writers Tara Isabella Burton and August Lamm both prefer desktops over laptops and especially over phones, so that the machine “lives” somewhere fixed, reminding them they are crossing into another world, one they will eventually need to leave.

The algorithmic internet is a glamour machine. Each video is designed tobe more gripping than the last

Guard your name with your life. The prohibition against revealing true names runs through every culture that believes in otherworlds – your name holds the essence of being itself. To give your name to otherworldly entities grants them power to summon you at will, call you into their world, and make you theirs forever. Evans-Wentz wrote about how people used “milk-names” and nicknames to hide baptismal names from the Good People, while in Germany, Rumpelstiltskin’s power ended the moment his name was spoken.

Online, names carry the same dangerous power. The teenage girl whose Instagram handle includes her full name and high school becomes trivially easy for obsessives to find, while the professional whose decade-old forum posts, made under his real name, surface during every job search remains haunted by his digital past.

We also witness inverse power of those who guard their names carefully: anonymous accounts become legendary precisely because no one knows who runs them, accumulating power independent of their creators. What we call “opsec,” the occultist calls wisdom.

Beware the fairy glamour – the fairy food, the fairy music. Esotericism and folklore are full of warnings about glamour. Countless peasants were lured into the Sídhe mounds by music too beautiful to resist or food too sweet to refuse, only to emerge years later, hollowed out. This is glamour in its older sense: not beauty alone, but enchantment that overwhelms the will.

The algorithmic internet is a glamour machine. Each video is designed to be more gripping than the last, anticipating desires before you even know you have them. You open the app to look at a funny clip and only surface again at 2 a.m. after watching an entire movie in three-minute bursts, your thumb scrolling without command. It makes the mundane world seem washed out: books feel slow, conversations dull, the physical less vivid.

Worst of all is how the online world impacts our perceptions of ourselves. Folklore warns against reflections in otherworlds. Often, the image gazing back isn’t you at all, but something meant to deceive you. Online, the same danger comes in two forms. Visually, through filters and endless selfies that make the reflection more beautiful than life until you don’t recognize yourself anymore, there is a sense of dissonance between how you present online and how you manifest physically that can cause real anguish. Psychologically, through the subtle warp of comment sections that leave you estranged from who you thought you were. In both cases, the mirror returns a distorted self, and the longer you stare, the harder it is to remember what you actually are.

Never apologize – and guard your emotions. In otherworlds, etiquette is survival. An apology can bind you; a thank you can put you in debt. Even answering when your name is called may deliver you into the wrong hands. Japanese folk tales warn: never show fear to yokai. Slavic ones: never be too polite to Baba Yaga. Silence, sometimes, is the only safe reply.

Esoteric writers said the same of the astral plane: dead thoughts mimic life when fed with attention, clinging until they become obsessions. Theosophists warned that strong emotions can generate “thought-forms,” semi-independent beings that take on a life of their own.

On social media, every reply to the swarm is treated as a fresh admission and every apology becomes proof of guilt. What begins as one angry tweet multiplies into thousands of echoes, a thought-form with its own momentum. Cancellation campaigns mutate long after the original offense is forgotten. Sooner or later, the target goes silent, but their explanations remain as monuments to futility. Do not post in anger, despair or ecstasy. Wait until the emotion passes, otherwise you release what you cannot call back.

Try not to accept their gifts or make bargains – you won’t have the upper hand. In folklore, gifts are rarely simple. They bind. Eat fairy food and you’re theirs forever. Put on enchanted clothes and you might never take them off. Accept hospitality and you owe more than you meant to give. Even treasure can be unreliable: gold crumbles into leaves by morning.

In the 2010s, we learned that on social media, we are the product. Viral fame becomes a cage more restrictive than the traditional sort. Communities that once felt welcoming demand endless performance. A stranger gives you a gift – a real gift, maybe it’s money or something off your Amazon wishlist or a book you’d posted about – and metastasizes into a stalker. The bargains we make online aren’t always explicit – whether it’s fame, a “free app” or an unexpected gift from a stranger.

Be careful what you bring back. Folklore warns against carrying souvenirs out of the otherworld. Stones from fairy rings, twigs from haunted groves – these turn to ash, or worse, bind the thief to misfortune. But not everything is forbidden. Bards were said to return from Fairyland with new songs, healers with charms or cures. The difference was discernment. Some artifacts from the internet are worth keeping: a piece of wisdom, an insightful podcast, a beautiful image. But others carry a hidden charge. A list of symptoms you saved “just to look in to” begins to warp your worldview. Screenshots of cruelty or betrayal become talismans of bitterness, drawing you back again and again. Not everything we find on the internet helps us.

Beware the changeling, beware possession. In folklore, a changeling was the child left behind when the Good Neighbors stole the real one, recognizable on the surface but subtly wrong: fretful, uncanny, draining the household’s energy while the true child lived elsewhere, scared, missing its parents. Children who spend too much time online come back altered, speaking in borrowed voices, their moods and desires shaped by the internet. They are still physically present, but something feels missing, as if the internet has carried the real child away and left only a substitute.

Do not post in anger, despair or ecstasy. Wait until the emotion passes, or you release what you can’t call back

Spiritualists spoke of the “silver cord” between astral and physical bodies, warning that, if the cord is severed, the soul could not return. The return must be physical through actual embodiment: cooking that requires chopping and stirring, walking without podcasts or Spotify “soundtracks” while feeling your feet hit the ground, swimming where water forces presence, gardening where earth gets under your fingernails.

Remember that returning from Fairyland, like becoming grounded again after the internet’s pull, isn’t easy but remains always possible through faith and, more importantly, through remembering your human body.

The portal is open and we cannot close it, but with these rules drawn from centuries of wisdom about the otherworld, we may yet walk the bright and terrible fields of the internet without losing ourselves.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply