The head of the Department of Government Efficiency (DoGE) wrote to all federal workers in the US asking them to explain in a brief email what they did last week. The exercise was intended to take no more than five minutes but led to howls from many employees. How could anyone expect them to perform such a task? How can one explain the intricacies of supporting transgender opera among the Inuit in such short order?

Happily, the new editor is not putting those of us on The Spectator’s payroll through any similar exercise. Nevertheless, something in the global vibe-shift perhaps impels me to mention a little of what I have been doing with my time. And the first thing that comes to mind is that while everyone else is swimming in a sea of acronyms, I might have something useful to say about the recent elections in Germany.

It has been my view for a very long time that most mainstream press coverage of politics on the European continent is pretty much bunk. I arrived at that realization after a period of some years when I was in a different European country most weeks, meeting with politicians and trying to work out who was who. There was a time when a lot of the media did that: within living memory British tabloids had correspondents in all the major European capitals. But today even the broadsheets have gone over to impossibly wide-ranging roles like “Europe correspondent,” which is only marginally more useful than the BBC’s “Africa correspondent.”

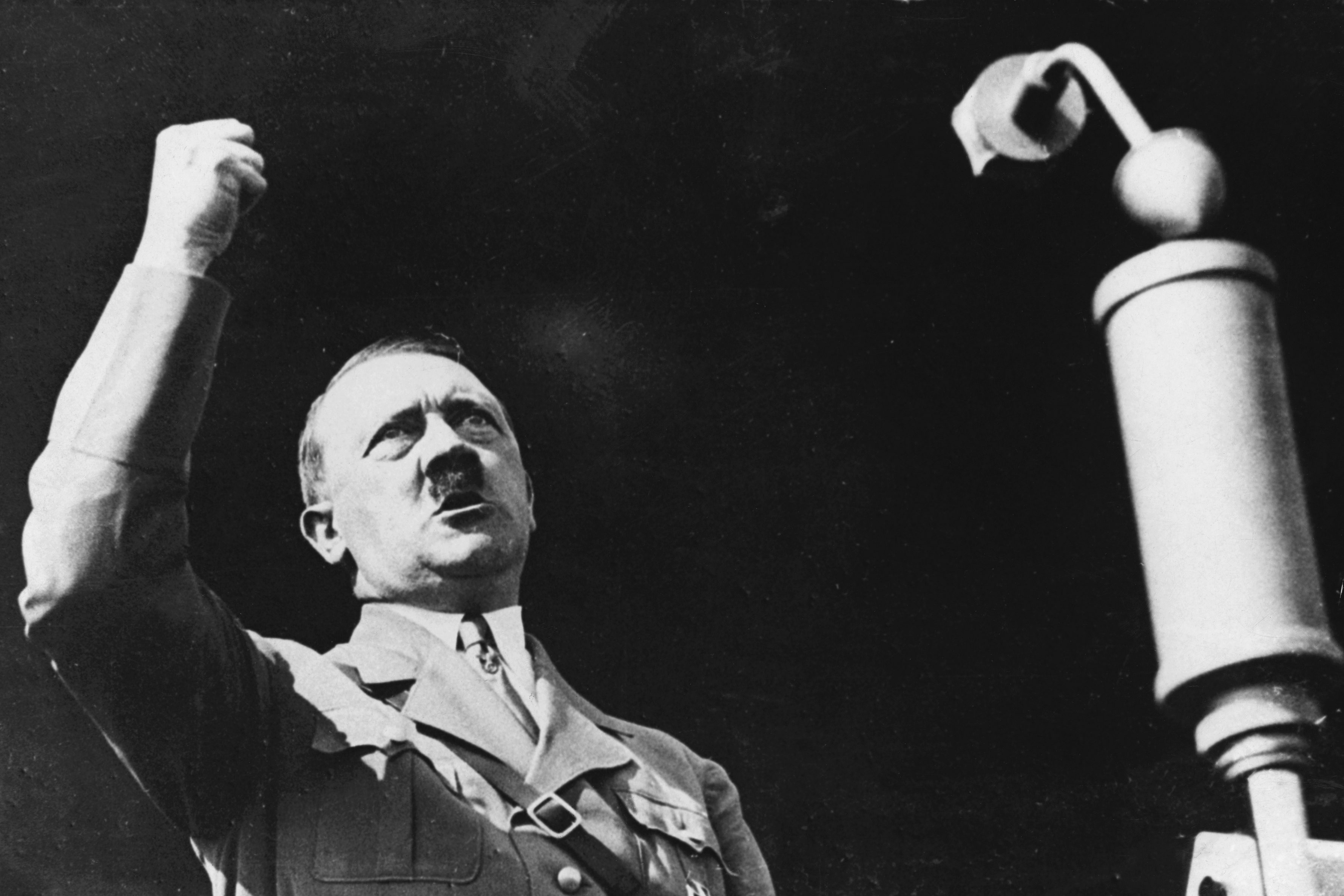

Another problem is that the few outlets that aspire to actually cover politics in Europe are prone to a law of British journalism which must someday be analyzed. This is the presumption that all left-wing parties (such as the charming government of Spain) should be assumed to be doing a jolly good job and be allowed to get on with it. By contrast, any centrist political party is to be deemed under caution unless it backs all the major left-wing causes of the day. And any right-wing party — including any that might dare just to be “conservative” — should be treated as though it is about to usher in the second coming of Adolf Hitler.

The AfD did not manage to ‘march to power’. But it did double its share of the vote

Personally, I have always found this a charming foible of the left-wing media. They are all for internationalism, fraternity, unity and so on, but seem to believe that most foreigners — certainly in Europe — are fascists in barely concealed disguise. And this interpretation of Europe seems to have lain behind most of the coverage of the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party, both before and after the federal election in Germany.

Some prominent non-Germans have taken the side of the AfD of late, on the apparent presumption that anyone who has been anathematized to such an extent must be good. But as I tried to explain to some of the American media this past week, the truth is that the AfD is a curate’s egg (a phrase that led to some of my American readers frantically googling).

However you phrase it, the idea that the AfD might be good in parts remains too subtle a point for much of the media in Germany and beyond. On one side are people rightly fed-up with cancel culture and name-calling and mainstream politicians ignoring the views of the public. They then react further to the large number of commentators desperate to write pieces with headlines like “Far-right rises in Germany.”

Yet many of the AfD’s policies are perfectly commonsensical. It is not as though the centrist parties have managed to get control of mass migration, to name just one form of political rocket-fuel. So if a party comes along that says it would really like to tackle immigration and stop the emerging new traditions of car-rammings and knife attacks then ordinarily they’d be credited with something. But modern European politics doesn’t work like that.

Several things make this even more complicated. Geert Wilders now heads the largest political party in the Netherlands. But some twenty years ago, when I first interviewed him in his office in the Dutch parliament, he was the only member of his party as well as its sole member of parliament. He was the only member because, as he admitted, if any right-of-center party starts up in continental Europe it will be called far-right by the media and its opponents. The small number of actual far-right types who still exist will then be the first to join — so destroying the party from the get-go. There is no reason why politics should be dictated or destroyed by such extremes. But that is how it goes. And this is how much of the political mainstream and activist left are actually happy for things to go.

Which brings me back to the AfD. As the election came closer there was much excited talk about how the party would storm the polls. The party encouraged some of this, as did its political opponents. And the problem upon a problem is that, as the party has grown some very unsavory types have indeed muscled into the AfD. The wiser party leaders spend a large amount of their time making sure to sideline or expel such people. That is a full-time job. But it is also a piece of political brain surgery at which many people would like to see the AfD fail.

If they do fail, to say that would be a catastrophe would be an understatement. A right-wing party in Germany of all places actually turning far-right would spell a nightmare for everyone.

The AfD did not manage to “march to power.” But it did double its share of the vote from the last election. A wise mainstream would notice this and decide (as the Danish center and left have) that sometimes you should listen to the public and adapt your policies accordingly. But most countries do not seem to have a wise mainstream. And so the problem will be put off until everything is worse.

Leave a Reply