If the nightmare of anticommunists during the Cold War was an endless future of totalitarian terror, the nightmare of today’s critics of liberalism is an endless future of constant social upheaval and atomization as a result of unchecked markets and radical individualism. Not a boot stamping on a human face forever, but a high-tech appliance in need of the latest upgrades — forever.

What many critics as well as defenders of liberalism tend to overlook is the possibility that liberalism — in the economy, in politics and in culture — will prove to be unstable and self-liquidating. To put it another way, a liberal social order tends to be an ephemeral transition between one non-liberal system or regime and another.

The ideal of most contemporary liberals, I think it is fair to say, is a vision of society as three self-correcting markets: an economic market, a political market, and a cultural market. I use the term “market” for all three spheres because today’s liberals in practice are guided more by the vision of self-correcting markets in academic economics than by the philosophies of John Locke or John Rawls.

In each of these three markets, we are supposed to believe, the normal condition is healthy competition among a plurality of rivals. In a market economy, competition prevents the formation of economic monopolies; any firm that temporarily attains a dominant market share inevitably will be whittled down to size by existing or new competitors. In the democratic political marketplace, parties will win only fleeting majorities and will sooner or later be turned out by their adversaries. In the realm of culture and ideas, free debate and contestation will ensure that no stifling orthodoxy can be imposed.

Liberalism, then, posits that society can be kept fluid and dynamic by never-ceasing competition for consumers, voters, and audiences for ideas and art. As long as there is free and fair competition in commerce, monopolies with market power will not appear. As long as there is free and fair competition in politics, one-party rule is not a danger. And as long as there is free and fair competition in academic life and the media industry, we need not fear that a single faction with a single point of view will capture education and journalism.

The basic assumption of liberalism, then, is that competition more or less naturally and automatically eliminates concentrations of power — market power, political power and cultural power. But this belief that competition and concentration are incompatible is an article of faith of the liberal creed that it is refuted by actual experience.

Let’s begin with the economic market. In the real world, completely competitive markets cannot exist, because perfect competition would soon drive down profits until they are the same as costs. In a perfectly competitive market, no firm would ever be able to exercise its market power to make a profit and capitalism could not exist.

Moreover, in certain kinds of industries — those characterized by increasing returns to scale, like manufacturing, and by network effects, like infrastructure grids — competition, far from restraining monopoly, tends to produce it. Each round of competition produces fewer and bigger rivals, until finally, in the absence of intervention by state antitrust or competition authorities, the most successful firm has established a monopoly or near-monopoly in its field. And a monopolistic firm need not cheat. It may simply be slightly more efficient or slightly more user-friendly than its rival, and this slight advantage is rapidly compounded by a kind of snowball effect.

Around 1900, there were dozens of start-up automobile companies in the US. By the 1920s these had been winnowed down to about a dozen and by the 1950s Detroit was dominated by the Big Three. The same process of elimination, following the later digital technology revolution, eliminated rivals like Dogpile and Inktomi to give Google a near-monopoly in the search engine industry and Microsoft a dominant position in software. Thanks to the advantages of scale, following deregulation of financial markets in the US, many small, protected state and local banks have disappeared, and winner-take-all dynamics has produced massive concentration in the financial industry.

The story is the same in the market of electoral politics. So-called dominant-party systems, in which a single party or coalition of parties maintains a majority for long periods without authoritarian measures, have been common in democratic countries. Parties like America’s New Deal Democrats, the Swedish Social Democrats, the Italian Christian Democrats, and the Japanese Liberal Democratic Party enjoyed periods of dominance and near-fusion with the government for decades at a time. In the United States today, every big city and college town is run by the Democratic Party. So much for the hope of the American founder James Madison in Federalist 51 that a multiplicity of interests would prevent prolonged dominance by any single political coalition.

We find the same pattern of monopoly and monoculture in the universities and establishment media. Instead of hosting vigorous debate among thinkers representing all shades of mainstream political opinion, American universities are monocultures in which upwards of 90 percent of professors describe are left-leaning Democrats. In the mass media, political and philosophical debate has been shut down by cancellation.

None of this should surprise us if we recognize that competition produces winners, whose monopoly of commerce, power or influence then fortifies them against challengers. Marxists were wrong about many things, but they were right that in many modern industries competitive capitalism tends to give way to monopoly capitalism. The same is true, as we have seen, of competitive politics and cultural and intellectual competition. In one area after another, not only do winners take all, winners also can keep all — not forever but for a very long time indeed.

The error of liberals, then, is to posit never-ending contests in politics, markets and the culture. But contests come to an end, and they do so by rewarding winners and penalizing losers. Meritocracy engenders aristocracy in which the winners then rig the competition to benefit their offspring. Free markets engender monopolies and oligopolies which are then insulated by their market power from competitors. The contest of ideas in universities and the media produces winners who then shut down the contest and ban any ideas other than their own.

Both champions and many critics of liberalism, then, treat liberalism as a possibly permanent social order, instead of merely a transition between different kinds of long-lasting non-liberal regimes.

What kind of non-liberal regime might succeed liberalism in the West? The conditions for a return of militarized, mobilized fascist or communist statism do not exist. More likely is a condition of unaccountable oligarchy and universal corruption, which I like to think of as mafiacracy.

Despite their differences, communism and liberalism both tend to weaken intermediate institutions and communities that are not controlled by elites and atomize and isolate individuals. The weakening of communist state power in Eastern Europe and Russia, far from producing a renaissance of social and civic institutions, has produced a kind of mafiacracy. The replacement of market competition by market power might produce a similar result in the West after liberalism mutates into something non-liberal. The regime would be a postliberal order, so to speak, but not the kind of which today’s postliberal thinkers are likely to approve.

Tyranny and incompetence are usually combined

Among others I have used the term “Brazilianization” to describe a future in the industrial nations of the North characterized by oligarchy, inequality, widespread corruption, and poor economic performance. As it happens, Brazil was the title of a dystopian science-fiction movie directed by Terry Gilliam in 1985. In a conversation with the philosopher John Gray, I suggested that the satire suffered from a confusion of purposes, because the dystopian regime was both tyrannical and incompetent. Oh, no, John replied, tyranny and incompetence are usually combined.

If I am right, then the aftermath of liberalism in the West is more likely to resemble contemporary Latin American dysfunction than the Central European totalitarianism of a century ago. A Mexican law professor, himself a victim of official harassment, once smiled and told me: “In Mexico, we view constitutions as aspirations, not laws.” A widely-shared proverb in Spanish America since colonial times has been Obedezco pero non cumplo — I obey, but I do not comply.

In many dysfunctional societies, basic goods can be achieved only through informal means, like bribes or purchases on the black market. Even the rich and powerful are forced to pay off the books to get things done. One of the characteristic social types in such regimes is the fixer. The classic example in the US is knowing somebody who knows somebody at City Hall who can get your ticket fixed. In societies in which intermediate organizations and civic ethics have decayed, you need to know somebody who knows somebody to get anything done — for a price.

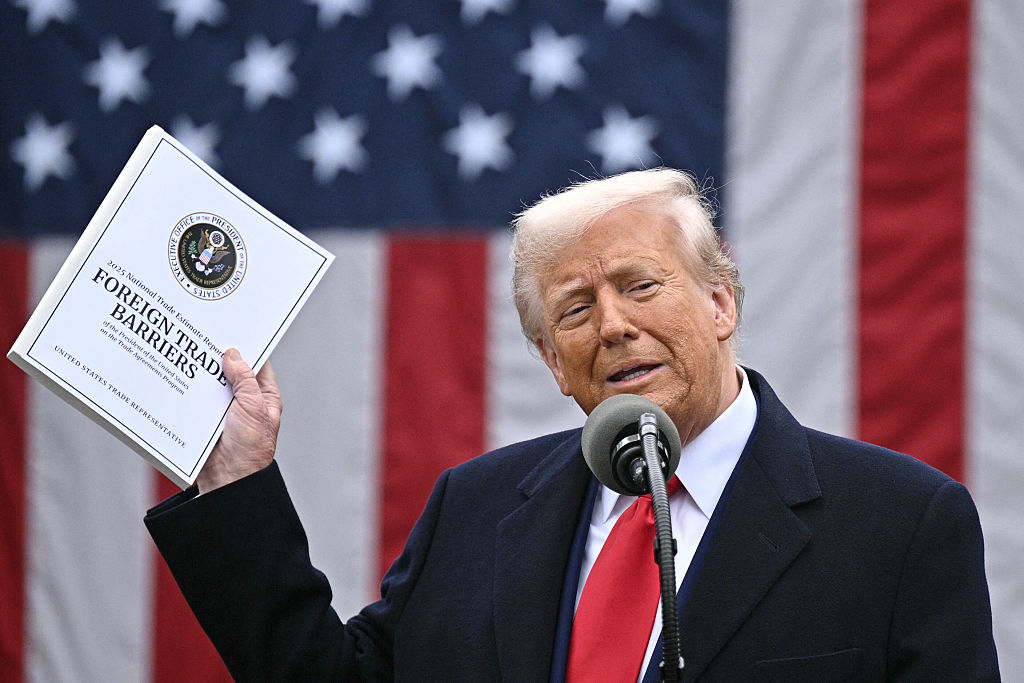

We are seeing the rise of the fixer economy in the allegedly liberal West. Increasingly market goods and public services that used to be offered to all customers or citizens on a universal basis now require additional charges. In the United States, for an extra fee, you can drive in the reserved express line on the highway, go through airport security faster, and see your doctor next week instead of next month or next year. Under Barack Obama the Affordable Care Act, designed to provide insurance to the uninsured on the basis of the liberal principles of consumer choice and market competition, was gamed by insurance companies in such baffling ways that the federal government itself had to pay fixers called “Sherpas,” after the guides who help climbers ascend Mount Everest, to help perplexed citizen-consumers fill out the incomprehensible insurance forms.

If I am right, then it is not enough for post-liberals and like-minded thinkers and reformers to oppose the radically individualistic and competitive version of liberalism. They must anticipate the kinds of non-liberal regimes into which liberal regimes over time may decay, regimes characterized by corrupt oligarchies at the top and an atomized population below.

A longer version of this speech was delivered at the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute Postliberalism conference in Cambridge on 13 to 14 December.

Leave a Reply