Bomb shelters have come a long way since the Blitz. As missiles from Azerbaijan rained down on Nagorno-Karabakh a few weeks ago, Hayk Harutyunyan and his family took refuge in a basement with wifi, an ensuite toilet and a makeshift mini-bar. There were 12 people crammed in there every night, he told me, ‘but we Armenians are very close as family, so we get on well’.

Indeed, sipping brandy with them in their shelter, I was reminded of that other Armenian clan, the Kardashians, who spend their time sitting around and chatting. Keeping up with the Harutyunyans, however, makes for more challenging viewing.

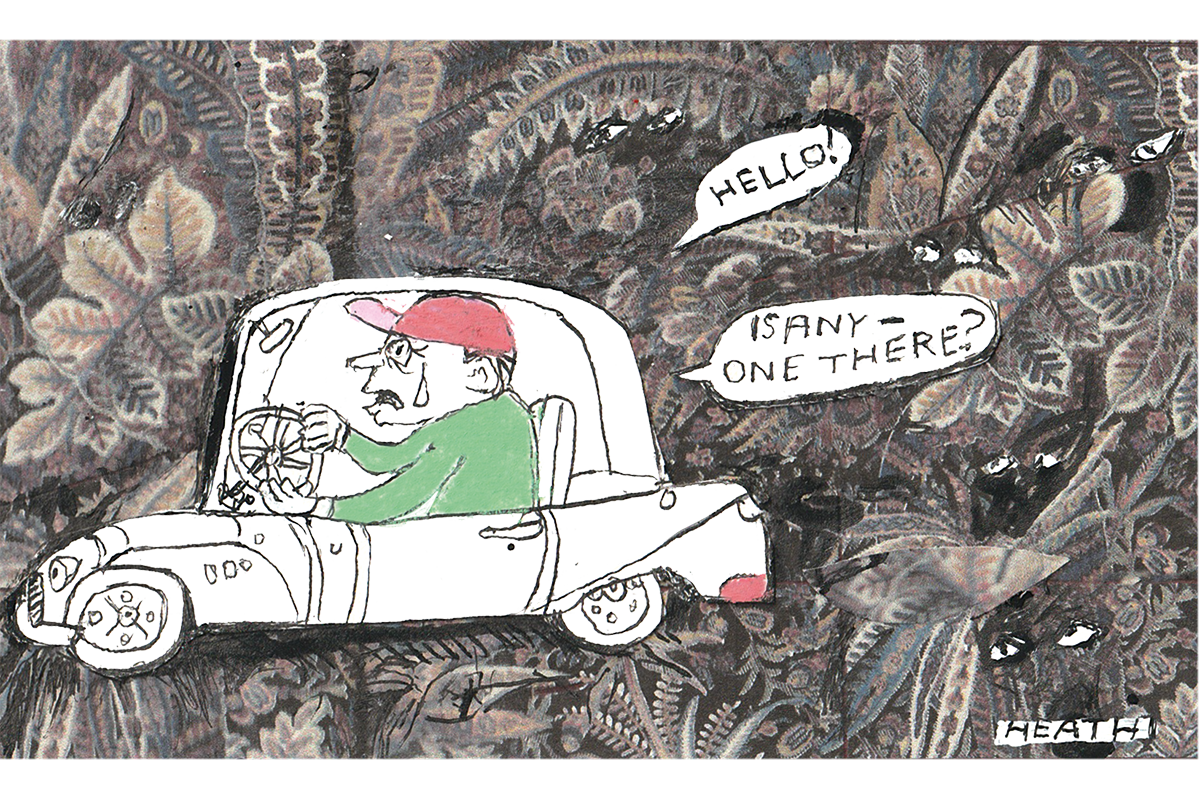

Armenia, a Christian democracy in a neighborhood dominated by Islamists and strongmen, has been left to fend for itself by the West. Neighboring Azerbaijan wants control of its Nagorno-Karabakh region, and though there has officially been a ceasefire since 1994 — it’s a ‘frozen conflict’ in diplomat-speak — the three decades since have looked less like peace and more like an undeclared Thirty Years War. At least 3,500 people have died in cross-border skirmishing, with both sides engaged in shelling, sniping and commando raids across Flanders-style front lines. And that’s not even counting the 1,200-plus casualties in the latest flare-up. On Monday night, after Azerbaijani forces captured the strategically important Nagorno-Karabakh town of Shusha, a ceasefire was agreed. But it’s one which makes most Armenians extremely uneasy. Many are protesting against the peace deal, and they remain on edge and ready for war.

For Nagorno-Karabakh’s 150,000 citizens, a state of constant readiness for war feels normal. In the time-warped Soviet-era capital, Stepanakert, murals and monuments extol the glories of the conflict. A well-drilled system of air-raid sirens gives people time to scramble into their bomb shelters. And everyone I met there had either a relative already serving on the front lines, or was about to volunteer for duty themselves. Even David, the gray-haired grandfather who acted as our driver, turned up in military fatigues some days.

For the rest of Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh is a sort of holy cause. At the end of September, when the fighting began again in earnest, some 10,000 Armenians volunteered to take up arms on the first day alone. Meanwhile, members of the 11 million-strong Armenian diaspora — mostly descendants of people who fled during World War One — send money and organize relief. Even Kim Kardashian cheerleads from the sidelines, broadcasting her support to her 67 million Twitter followers.

Armenians, including Kim Kardashian, contend that Nagorno-Karabakh has historically always been Armenian, and was lumped into Azerbaijan only as a result of imperial scheming by Stalin. Having fought tooth and nail to secede in the 1990s, they claim to have far more stomach for the fight than the Azerbaijanis. ‘Azerbaijan is just fighting for territory, whereas we are fighting for our homeland’ is the popular mantra.

But the past six weeks of fighting have shown that bravado only gets them so far. Oil-rich Azerbaijan now has far better weapons than they do, including drones that can hit once-formidable artillery positions in Nagorno-Karabakh’s mountains. Azerbaijan’s authoritarian president, Ilham Aliyev, has also been emboldened by backing from President Erdogan of Turkey, for whom Azerbaijan is part of a greater Turkic empire. ‘Why don’t the Christian nations of the world come and help us?’ Hayk Harutyunyan’s aunt asked me.

Erdogan has been accused of lending Aliyev behind-the-scenes military support, including battle-hardened Syrian mercenaries to act as shock troops. So it’s easy to see why Armenia feels it should get more support from the West than the odd tweet from Kim K. Russia, its traditional ally, has so far done little except broker a couple of ceasefires which both sides promptly violated. But it’s not quite clear that Uncle Vlad is a good thing for Armenia any more. The country had a successful ‘color revolution’ two years ago, ushering in a scruffy ex-hack, Nikol Pashinyan, as prime minister. His government has introduced much-overdue democratic reforms — so much so that some of the diaspora have been returning, convinced the old country finally has a future. All of which, of course, is now at risk.

The unpopular peace deal is a disaster for Pashinyan, who may now be overthrown. Aliyev has gloatingly described it a ‘capitulation’ because Azerbaijan will get to keep hold of Shusha, as well as various other bits of recaptured territory.

[special_offer]

Yet nobody can really accuse Aliyev of mounting an illegal land grab, because internationally, the enclave is still recognized as part of Azerbaijan. He says all he wants to do is repopulate the area with Azeris displaced during the 1988-94 conflict, and reestablish Azerbaijani control.

The ethnic Armenians living there, he promises, will not be harmed; his advisers argue that life under Azerbaijan control might be better than life in an illegal statelet which the rest of the world does not recognize. Yet after three decades of low-level war, and six weeks of intense shelling, the chances of multicultural harmony are remote.

Armenians still remember the case of Lieutenant Ramil Safarov, an Azerbaijani army officer who axed a sleeping Armenian colleague to death while the pair were on a Nato ‘Partnership for Peace’ training exercise in 2004. He was later pardoned by Aliyev, and today is celebrated as a national hero by many Azeris. If that’s any taste of how Azerbaijan sees them, Armenians say, maybe it’s best not to take Aliyev at his word.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.