Everything from the flintlock rifle to the dialogue was planned — somehow people often don’t realize that, even when there’s a Hollywood actor on stage. When Charlton Heston raised the prop above his head at the 2000 NRA convention and bellowed, “from my cold dead hands,” those gathered in Charlotte reacted just as the ghostwriters thought they would. It didn’t matter that the line in question had been a bumper sticker for decades, or that the septuagenarian Oscar-winner was reciting a phrase Vincent D’Onofrio had parodied just three years earlier in the blockbuster Men in Black. Viewers of the film today won’t realize the cart is pulling the satire horse until they check IMDb.

You can picture the ad executives from Ackerman McQueen nodding knowingly at Wayne LaPierre the moment it happened. Not that the NRA CEO needed much convincing. LaPierre may have made his bones as an anonymous lobbyist who shopped off the rack, but he recognized that a group representing millions of Americans of voting age could use some flash. It wasn’t long after LaPierre took the reins in 1991 that celebrities started going public with their support for gun rights. Not only Heston, but the Mailman Karl Malone, the rocker Ted Nugent, the mustachioed straight man Tom Selleck. LaPierre and his admen recognized early on that America had entered the Age of the Celebrity — and thanks to Ackerman McQueen’s speechwriters, Charlton Heston (NRA president from 1998-2003) and his rifle became as inseparable in the public imagination as Travis Kelce and Taylor Swift are today. Under LaPierre’s watchful eye, NRA membership doubled, pro-gun laws proliferated. Second Amendment rights triumphed at the smallest of district courts all the way up to the Supreme Court.

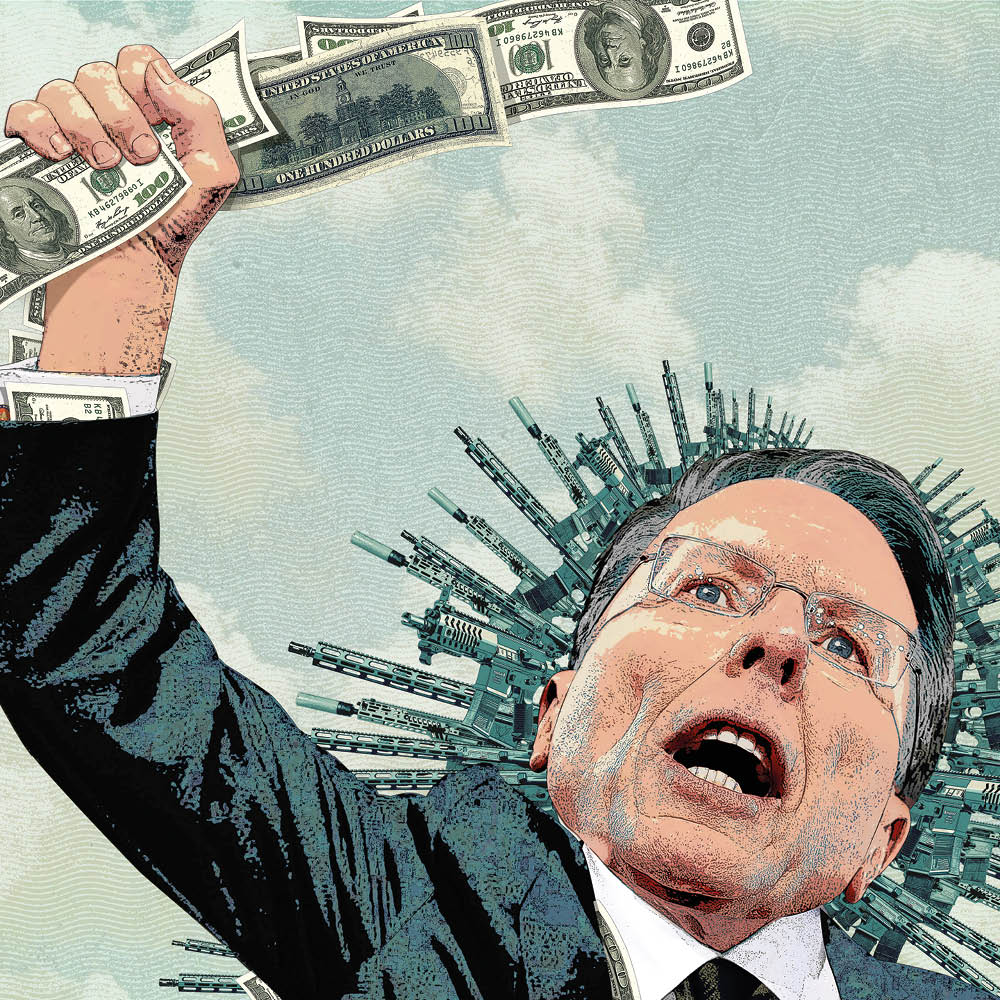

In January, LaPierre announced his resignation in a statement bearing the polish of 2023 PR rather than the brash attitude he helped pioneer alongside Ackerman McQueen. No more talk of lifeless extremities, just the lifeless rhetoric that could just as easily apply to saving the whales or plugging the ozone layer: “My passion for our cause burns as deeply as ever,” he said in his resignation statement. His statement pointed to health considerations, which his lawyers said include “chronic Lyme disease” and “significant cerebral volume loss,” among other factors. It hit the wires on the eve of his civil trial on charges of misusing charitable assets. After decades of losing to LaPierre at the ballot box and on Capitol Hill, Democrats led by New York attorney general Letitia James had finally found a way to bring him down. Prosecutors allege LaPierre lived large at the expense of membership and employed shady accounting tricks in cooperation with the ad agency to cover it up.

James once branded the NRA “a terrorist organization,” but she didn’t need the PATRIOT Act to provoke LaPierre’s ouster. She settled for the standard playbook of going after financial impropriety — bespoke suits, family flights, yachts — to prosecute the man NRA state chapter president Tom King called “the Second Amendment GOAT.” and fellow NRA board member Niger Innis called “a civil rights leader in his own right.” The relationship that helped drive all that influence and star power has now become the vehicle for LaPierre’s unraveling.

At LaPierre’s peak, the NRA rolls swelled to about 5.25 million dues-paying members; revenue routinely eclipsed $400 million in each year between its collection of nonprofits and political action committees. That earned the NRA a truly nationwide reach that extended throughout American politics, law and culture. LaPierre wasn’t the only vital player at the NRA during his tenure — and the NRA wasn’t the only one responsible for the advances Second Amendment advocates made in the last half century. But it’s unlikely many of them would have happened without the group or its leader.

LaPierre’s star turn came working behind the scenes as the head of the NRA’s lobbying arm. Under his stewardship from 1991 to 2024, the group accomplished what may be the organization’s greatest federal legislative accomplishment. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan signed the Firearms Owner Protection Act into law. It banned the government from keeping a registry of all guns, added protections for gun owners traveling from state to state, allowed ammo shipments through the mail and restrained ATF inspections of gun dealers, among other things. The achievement was no small feat in the aftermath of the assassination attempt that nearly killed the president and gave birth to the Brady Fund — the most prolific gun control group of the era.

“Passing legislation is ten times harder than killing it. It’s easy to kill legislation,” Judge Philip Journey, a former NRA board member, told The Spectator. But even in defeat, LaPierre found ways to achieve victory. When Bill Clinton signed the ban on so-called “assault weapons” in 1994, LaPierre mobilized millions in time for the midterm elections. The GOP picked up eight Senate seats and flipped the House for the first time in decades.

“They had a major role in the Republican Revolution,” Journey said. “It was clear that NRA members played a key part, and Wayne oversaw activating them and persuading them to get involved in the process.” The NRA managed to sustain that attention over the ensuing years of the Clinton era. George H.W. Bush may have resigned from the NRA following LaPierre’s condemnation of federal agents as “jackbooted government thugs” after Waco, but his son knew better than to cross the organization. George W. Bush beat Al Gore in large part because of the former vice president’s support for stricter gun laws — Heston hammered the point home in his iconic convention speech.

The “assault weapons” ban expired as a result of Bush’s victory, but the local and state accomplishments may outshine all the others during LaPierre’s tenure. Nowhere is that more apparent than in how concealed gun carry is now regulated throughout the country. In 1988, most states effectively banned concealed carry. By 2013, none did. Before 2001, only Vermont allowed lawful gun owners to carry concealed without a permit. Today, more than half of states do.

The NRA also left its mark on the courts. Through grants, it supported much of the legal scholarship arguing that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to keep and bear arms. It struck paydirt when the Supreme Court cemented that fundamental right in District of Columbia v. Heller in 2008. And, while the NRA’s $50 million 2016 investment in Trump didn’t result in significant legislative accomplishments, it did pay off in the form of three Supreme Court appointees who signed on to a second landmark case that expanded on Heller. The vehicle for that ruling, New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen, was brought by Tom King’s NRA state affiliate and financially backed by the group’s lobbying arm.

The NRA is regarded as a juggernaut in the liberal imagination, not for its jurisprudence or its technical legislative accomplishments, but for the power of its messaging — and that is why LaPierre’s ties to Ackerman McQueen will be central to his legacy, for good and ill. Much of what the average person knows about the NRA is the result of work done by Ackerman. Everything from the group’s “I’m the NRA” ad campaign to its most famous speeches and in-house TV network was run by Ackerman over the years. The ad agency didn’t just save its most famous lines for Oscar-winning actors. They supplied the 2012 speech in which LaPierre declared, “The only thing that can stop a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun,” in response to the Sandy Hook shooting.

But even before Letitia James set her sights on the NRA, there were those who called LaPierre’s relationship with the ad agency into question. As long ago as the 1990s, some NRA personnel openly fretted about the organization’s spendthrift ways. Heston had been put on the NRA board at Ackerman’s behest and elevated to NRA president as part of a successful effort to outmaneuver internal critics who wanted to cut the ad company out of the organization over concerns about its relationship with LaPierre, the amount it charged the group, and the methods it used for billing those fees.

LaPierre can be forgiven for thinking himself bulletproof. Democratic politicians had been attacking him and his organization personally for decades without results — “I’m coming for you, NRA,” Joe Biden said in a 2020 primary debate. “And I’m going to beat you.”

Biden received an assist from his opponents. Ackerman McQueen, which did not return The Spectator’s requests for comment, received upward of $40 million a year by the end of its relationship with the NRA. The firm often produced little or no documentation for the expenses it was charging the gun group. The lack of transparency and lax oversight allowed executives from Ackerman and the NRA to create schemes that resulted in paying lavish personal expenses for LaPierre and others, ultimately from tax-exempted funds contributed by NRA members. Alleged expenditures ranged from millions in private plane and helicopter rides for LaPierre and his extended family to six-figure shopping sprees at Los Angeles custom-suit shops.

LaPierre, who testified over the course of three days in January wearing a plain dark suit and showing little sign of medical issues, conceded having paid those expenses, justifying them as security or job-related — the suits, for example, were worn to look the part of a swaggering political power-player. LaPierre said he has repaid hundreds of thousands to the group for taking “excess benefits.” The NRA has maintained that those repayments and the firing of a number of other executives, including a former treasurer, are evidence the group has reformed itself.

Not every gun rights supporter is convinced. “He has a responsibility to members, and I think he’s let everybody down,” said Judge Journey, the erstwhile NRA board member who testified at the beginning of the trial. “I suppose he probably believed he was entitled to it, considering what he’s done for the group. And I can understand that, but we all know that’s wrong.”

The trial could see LaPierre barred from ever working with the NRA, or any other nonprofit, again and force him to repay millions more to the gun group. It might also result in the court appointment of an overseer with the power to reshape how the organization operates. That could further downgrade the effectiveness of the NRA. But the corruption allegations themselves have already taken a severe toll. The group has lost more than a million members since 2018 and seen its revenue cut in half as a result. In 2020, it was unable to muster even half of what it spent in 2016 to elect Donald Trump, and spending may fall even further in 2024, setting off alarm bells among GOP and internal strategists.

“The National Rifle Association of America is at a watershed moment in its 153rd year,” Owen “Buz” Mills, an NRA board member, recently wrote in a letter to his colleagues calling for change. “Our leadership has admitted in courts and depositions to misappropriation of donors’ funds and unauthorized use of assets. They have admitted condoning the misuse of donor funds by others employed by the NRA. The leadership has for years abused their position and trust placed in them by our members and benefactors.”

Journey is more direct: “The members don’t trust him anymore, and I’m afraid that’s going to be a big part of his legacy… it’s tragic.”

There’s little doubt LaPierre has left the NRA a group on the brink following a 2021 strategic bankruptcy to escape New York for Texas as well as the recent plunge in revenues. That it continues to hold any political power is a testament to his effectiveness over the years. Even with the spending scandal, President Biden has been unable to resurrect the “assault weapons” ban and settled for much more modest restrictions in the 2022 Bipartisan Safer Communities Act.

The NRA, still 4 million members strong, was around long before Wayne LaPierre. It may well survive his departure and the legal troubles surrounding it. But, whatever happens, LaPierre’s mark on the group is deeper and likely to last longer than that of any past leader, Heston included.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply