If I had a penny for every time I have been told that Russian president Vladimir Putin only wants respect. Or that he is only interested in eastern Ukraine. Or that if Kyiv is only denied NATO membership, then he will call off the tanks.

Well, in the last seven days President Donald Trump has given Putin all this and more.

And, though it is still early days, so far the war is showing no sign of slowing. And what has the man who wrote The Art of the Deal asked for in exchange for all this diplomatic largesse? Absolutely nothing.

In fact, the only substantive demand Trump has made so far is of the Ukrainians. Last week Washington sent Treasury secretary Scott Bessent to Kyiv with an extraordinary demand.

Bessent presented President Volodymyr Zelensky with a document to sign which would hand over the rights to half of all Ukraine’s rare earth minerals — of which it has trillions of dollars worth — as recompense for weaponry Washington provided under the Biden administration.

This is the equivalent of inviting a friend in need to a free dinner, and then later presenting them with a bill for many times the cost.

The events of the last week have been so dizzying that — lest we become punch drunk — let’s do a quick recap.

On February 12, Trump spent ninety minutes on the phone with Putin. Both leaders talked about how great their own and each other’s countries were, and Putin congratulated Trump on his election campaign and his penchant for “common sense” solutions.

Trump said that the two leaders would probably meet again soon in each other’s countries.

Trump then called Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky to inform him of his conversation with Putin, and to tell Zelensky that Putin wanted peace.

On the same day, if my notes are correct, defense secretary Pete Hegseth said that Ukraine will not get back the land it has lost to Russia. He added that NATO membership for Kyiv is off the table.

It was left to Kaja Kallas, the EU foreign policy chief who hails from Estonia, a country that knows the Russians only too well, to say what many others were thinking: “Why are we giving [Russia] everything they want, even before negotiations have started?”

Next, Vice President J.D. Vance offered Putin another unsolicited concession. He said that there would be no US forces deployed to Ukraine. Any deal would be left to the Europeans to police. If those forces were attacked, he added, they would not be covered by NATO’s Article 5 mutual-defense guarantee.

At this point, on February 14, Zelensky, Vance and much of the leadership of European defense and politics, traveled to Munich for the annual security conference.

Zelensky reminded them all of the 1938 Munich agreement in which Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister, signed over the Czech Sudetenland to Adolf Hitler in exchange for guarantees he would advance no further. (Chamberlain, incidentally, was greeted as a great peacemaker at the time.)

Then Vance gave a speech that barely mentioned Ukraine or security. Instead of worrying about Russia, he told the leaders of Europe, they should worry about themselves.

He cited a recent Romanian presidential election won by a man called Călin Georgescu, an unknown until he appeared on TikTok on a white horse.

(When it transpired that Moscow had meddled in the vote with a sophisticated social media campaign, the Romanian courts declared that election rules had been broken and ordered that it should be rerun.)

Vance said that this was evidence of a lack of democracy in Europe. Europe, he said, was more at risk from progressive policies — he cited a few more fringe issues to back up his claim — than from Russia, China or any external enemy.

To say that Europe’s good and great were left open-mouthed would be an understatement.

The Munich Security Conference has, of course, thrown up surprises before.

Putin’s speech in 2007, when he excoriated the West for allegedly treating Russia poorly, has gone down as one of the turning points of post-Cold War history.

Perhaps Vance was only saying what he thought “the new sheriff in Washington” (his words) wanted to hear. Perhaps he felt he had been eclipsed by the radicalisms of Elon Musk and wanted to win back the boss’s favor.

But if talk about seizing Canada, Greenland and Panama had been the sartorial equivalent of removing a few frilly outer garments by the new US administration, Vance’s speech was, at least for the Europeans, a full striptease.

It revealed the new Trumpian vision for the world in all its shocking nakedness. The US would champion the AfD — the German party of the far right — and a questionable Romanian on a horse, while admonishing Europe for worrying about Putin.

And so, back to the man in the Kremlin.

To imagine that Putin wants only this, or only that, is at best speculation, at worst self-delusion. During my last trip to Russia proper, way back in 2017, officials and academics were already telling me that Moscow was at war with the West.

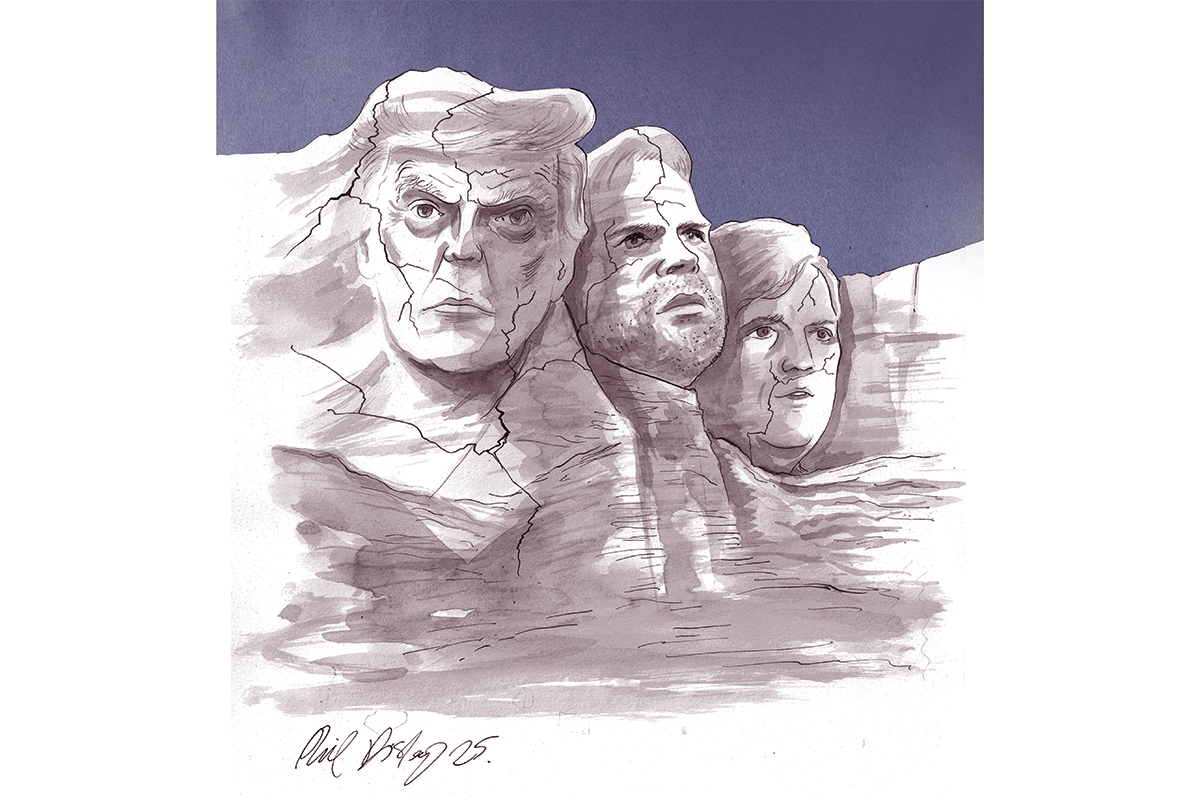

And, as far as Putin is concerned, it seems to be an all-consuming war to which he will devote Russia’s considerable resources. After all, in his eyes, it is his best chance to win a legacy that will put him in the pantheon of expansionist Russian greats such as Catherine and Peter.

Set against this push from the East, what does the West have? Unhappy electorates who don’t want to pay for bigger armies and eastern European populists who act more as Moscow’s proxies than stand-up members of the clubs to which they belong.

And an America which is not only terminating its services as the world’s policeman — that is perhaps something we expected — but it is also turning predatory. And that is something we didn’t expect.

Tellingly the first demands of the new US administration have not been from the world’s aggressors, but from their victims. The Palestinians should leave Gaza so it can become a US real estate development. The Ukrainians should hand over their rare earth minerals (for past favors rendered).

Autocratic China is rising. Dictatorial Russia is on the march. And the cop we depended on to keep us safe, has not so much retired, as morphed into a predatory mafiosi.

Human nature tends to be optimistic. In early 1992 few in Sarajevo thought there would be war. In early 2022 most believed Russia would not invade Ukraine. In Afghanistan in 2011 diplomats told me with confidence that the defeat of the Taliban was only a matter of time.

I do not want to be a doomsayer. I am generally of sunny disposition. But certain realities are now staring us in the face. And we must dare look. Only once we have opened our eyes and taken in the rainclouds and lightning ahead can we begin to chart our path through a very stormy sky.

Leave a Reply