Vladimir Putin’s actions have shocked many Western observers over the past few days. But his moves bear all the hallmarks of one of his predecessors: Joseph Stalin.

Last Monday, the Russian Duma passed a direct appeal to Putin to recognize the Russian-controlled separatist states of Donetsk and Luhansk. The Russian president first said he would not immediately recognize the so-called republics. The reason for this was he wanted it to appear that when he finally did recognize them as independent republics, he was simply reacting to popular pressure from below.

This is straight out of the Stalin playbook.

In 1922, Stalin simply proposed that his own government would absorb the governments of five other republics (Ukraine, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia):

If the present decision is confirmed by the Central Committee of the RCP, it will not be made public, but communicated to the Central Committees of the Republics for circulation among the Soviet organs, the Central Executive Committees or the Congresses of the Soviets of the said Republics before the convocation of the All-Russian Congress of the Soviets, where it will be declared to be the wish of these Republics.

The interaction of the higher authority (the Central Committee) with its base was not only abolished, it was re-staged as its opposite. The Central Committee decided what the base would ask the higher authority to enact, as if it were the will of the people.

The most conspicuous case of this Stalinist re-staging occurred in 1939, when the three Baltic states freely asked to join the Soviet Union, which granted their wish.

What Stalin did in the early 1930s was simply a return to the pre-revolutionary czarist foreign and national policy. For example, the Russian colonization of Siberia and Muslim Asia was no longer condemned as imperialist expansion, but was celebrated as the introduction of progressive modernization.

In a similar way, Putin brought together his security council last Monday and asked each of its members whether they supported the decision to recognize the independence of the self-proclaimed republics of Donetsk and Luhansk. When the turn came to Sergei Naryshkin, the foreign intelligence chief, he confused the precise script:

He first suggests that the West be given one last chance to return to the Minsk agreements, which could be done by giving the West a short-term ultimatum. Putin interrupts him dryly: “What does that mean? Are you suggesting we start negotiations or recognize sovereignty?”

Naryshkin starts to stutter, he doesn’t know what to say, he mumbles “yes” then “no,” and his face turns white for seconds that seem to last an eternity. “Speak clearly,” Putin interjects.

Feeling the pressure, the spy chief does a U-turn and goes one step further: he says he supports the annexation of Donetsk and Luhansk into the Russian Federation.

But he is again called out by Putin: “We’re not talking about that. We’re talking about recognizing their independence or not. Yes or no?”

So the nervous Naryshkin takes back what he said once again: yes, yes, he supports it. “Thanks, you can take your seat.”

Naryshkin first proposed too mild a version (just another ultimatum to the West), and then, in an act of obvious panic, he went too far and said that he supports the regions’ integration into Russia.

As one commentator put it: “The dramatic intensity of the scene would make it stand out in any movie or piece of fiction, but it’s not fiction.”

This scene tells more about the situation in Russian top circles than a heap of secret reports. Sergei Naryshkin, the head of foreign intelligence, the guy whom everybody should fear because of the data he may possess, stutters with his face blank and then is told to take his seat like a schoolboy who finally muttered the right answer.

This is how consultation with subordinates to hear “the voice of the people” works in Russia today. We are rarely given the chance to openly see how the mechanism works.

Although in January 2022 the Communist Party of Russia proposed the motion to appeal to Putin to consider the two regions’ recognition — Putin, playing a patient legalist, rejected the appeal — it’s crucial to bear in mind that the ongoing invasion is the final act of rejecting the last remainders of the Leninist tradition in Russia.

The last time Lenin made headlines in the West was during the Ukrainian uprising in 2014, which toppled the pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych. On TV, we watched enraged protesters tear down statues of Lenin in Kyiv. These furious attacks were understandable, insofar as Lenin’s statues functioned as a symbol of the Soviet oppression, and Putin’s Russia is perceived as a continuation of the Soviet policy of subjecting non-Russian nations to Russian domination.

But there was nonetheless a deep irony in watching Ukrainians topple Lenin’s statues as an assertion of their national sovereignty. The golden era of Ukraine’s national identity was not during Czarist Russia (when Ukrainian self-assertion was thwarted), but during the first decade of the Soviet Union, when they established their full national identity. In the early 1920s, Ukraine saw a national resurgence in arts and literature, actively encouraged by their communist leadership, who followed a policy of “Ukrainization.” Mykola Skrypnyk, Lenin’s leader in Ukraine, also oversaw a rise in the spread of the Ukrainian language.

This “indigenization” followed the principles formulated by Lenin in quite unambiguous terms:

The proletariat cannot but fight against the forcible retention of the oppressed nations within the boundaries of a given state, and this is exactly what the struggle for the right of self-determination means. The proletariat must demand the right of political secession for the colonies and for the nations that “its own” nation oppresses.

Unless it does this, proletarian internationalism will remain a meaningless phrase; mutual confidence and class solidarity between the workers of the oppressing and oppressed nations will be impossible.

Lenin remained faithful to this position to the end — and Stalin reversed Soviet policy after he took power. In his last struggle against Stalin’s project for a centralized Soviet Union, Lenin again advocated the unconditional right of small nations to secede (in this case, Georgia was at stake), insisting on the full sovereignty of the national entities that composed the Soviet state. No wonder that, on September 27, 1922, in a letter to members of the Politburo, Stalin openly accused Lenin of “national liberalism.”

Putin’s foreign policy is a clear continuation of this czarist-Stalinist line. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, according to Putin, it was the turn of the Bolsheviks to aggrieve Russia:

Ruling with your ideas as a guide is correct, but that is only the case when that idea leads to the right results, not like it did with Vladimir Ilyich. In the end that idea led to the ruin of the Soviet Union. There were many of these ideas such as providing regions with autonomy, and so on. They planted an atomic bomb under the building that is called Russia and which would later explode.

In short, Lenin took the autonomy of the different nations that composed the Russian empire seriously and questioned the Russian hegemony.

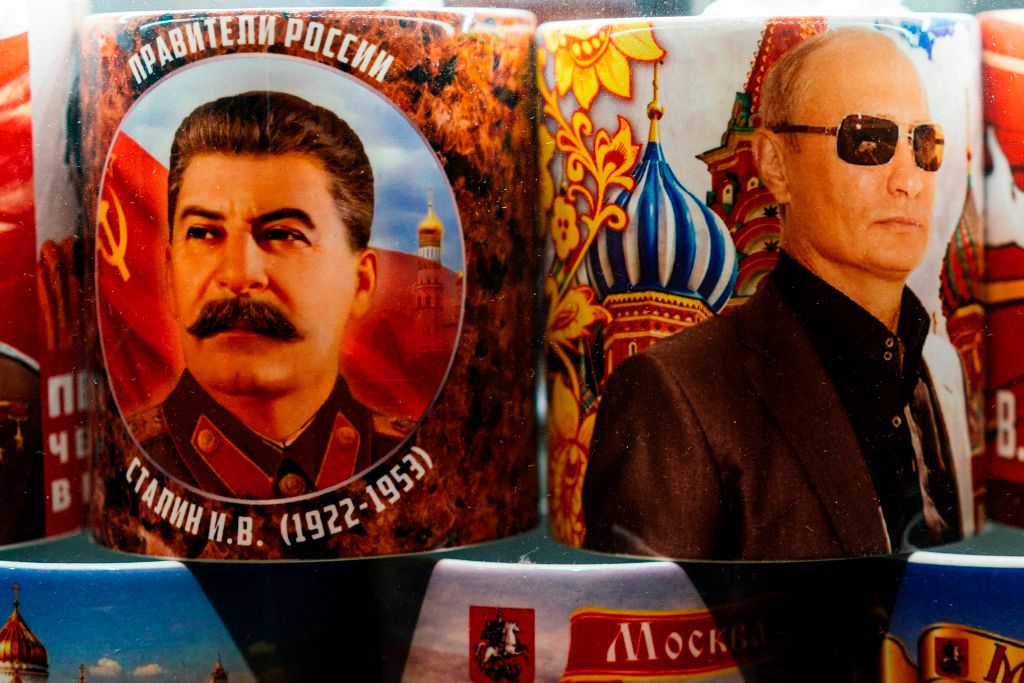

No wonder we can see Stalin’s portraits again during military parades and public celebrations in today’s Russia, while Lenin has been obliterated. In a large opinion poll from a couple of years ago, Stalin was voted the third greatest Russian of all time, while Lenin was nowhere to be seen.

Stalin is not celebrated as a communist, but as the restorer of Russian greatness after Lenin’s anti-patriotic “deviation.” When Putin announced last week’s military intervention in the Donbas region, he repeated his old claim that Lenin, who rose to power after the downfall of the Romanov royal family, was the “author and creator” of Ukraine: “Let’s start with the fact that modern Ukraine was entirely created by Russia, more precisely, by the Bolshevik, Communist Russia. This process began almost immediately after the 1917 revolution.”

Could he have been any clearer? All those leftists who still have a soft heart for Russia (Russia is the successor of the Soviet Union, Western democracies are fake, Putin opposes US imperialism…) should fully accept the brutal fact that Putin is a conservative nationalist.

Russia is not just returning to the good old Cold War with its set of firm rules. Something much crazier is happening: not cold war but hot peace — peace that equals a permanent hybrid war where military intervention is declared to be peacekeeping humanitarian missions against genocide. As Russia’s rubber-stamp parliament put it, “The state Duma expresses its unequivocal and consolidated support for the adequate measures taken for humanitarian purposes.”

Welcome to the new real.