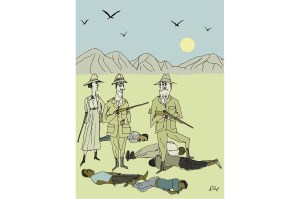

When I visited Maaloula in southwest Syria in 2016, the Jabhat Al-Nusra (the predecessor of the Hayat Tahrir Ash Sham jihadis, who have toppled Bashar al-Assad) had systematically destroyed and desecrated the town’s churches and monasteries. Orthodox nuns were kidnapped and held to ransom, only freed after the Syrian government agreed to release extremist prisoners. During my visit, I was told again and again that young men had been singled out and executed when they refused to convert to the extremists’ version of Islam. Some of the most moving moments in my life have been to pray with the townsfolk and help to rededicate an ancient altar that had been desecrated by the militants.

Maaloula isn’t just another small town caught in the crossfire of Syria’s brutal civil war. For Christians, its importance lies in the fact that it is one of the last remaining communities to speak Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic, the language of Jesus Christ, the Holy Family and the Apostles. Were this community to be destroyed, something precious and irreplaceable would be lost.

Of course, Maaloula is not the only atrocity experienced by Christians during this long drawn-out conflict. There are many clergy who were kidnapped and still have never been found, such as my friend Mar Yohanna Ibrahim, the Syrian Orthodox bishop of Aleppo, and Paul Yazigi, bishop of the Greek Orthodox Church in Syria. We must presume that they have been killed.

It is alarming, therefore, to learn that Maaloula is, once again, under attack. Multiple reports are saying that the extremist families who were removed from the town after it was recaptured by the army after 2016 are now returning. Christians there are receiving threats, being shot at and their property is being confiscated. After the last attacks, Christians, like other ethnic and religious groups, had armed themselves to protect their communities. This is being used as an excuse by rebel forces to stage armed operations against “pro-Assad militias.”

One element in the confusing mix that is Syria today is the presence of large numbers of foreign fighters from the China’s Uyghurs, Uzbeks from Central Asia, Chechens from Russia, Afghans and Pakistanis. The incident of the burning of the Christmas tree in Suqaylabiah, another Christian-majority town, was the work of some of these foreign fighters, as the new regime has acknowledged. It is worrying that these fighters are now embedded in the army and some have been appointed to high ranks within the armed forces. It has also been declared that they will be granted Syrian citizenship because of their fighting during the rebellion against the Ba’ath Party and President Assad. How will these fighters, with their historic rejection of plural societies, be integrated into a country known for its ethnic and religious diversity?

The protests by Christians in Damascus over the Christmas period show that there is widespread anxiety within the Christian population of what the future will hold for them. Their population has already been reduced drastically during the civil war and the extinction of some of Syria’s oldest communities would be a tragedy.

Of course, what may be happening to the Christians cannot be separated from what is happening to other vulnerable groups. The BBC has reported attempted confiscations of Alawite property in Latakia province by rebel groups and there have been reports of summary executions of captured Christian and Alawite soldiers by some groups. Given their experience of Islamic State in Iraq, the Yazidis are also anxious about the future, as are the Druze. I understand that Armenians have already begun to flee.

What accountability is there for the country’s new leadership?

The Ba’ath Party was a secular party, modeled on national socialist, that is to say, fascist lines. Assad was at its head, but it was not a one man show. Syria was governed as a virtually one-party state by a system that had remained resilient until now. While severely curtailing political freedom and plurality, the system allowed a measure of personal, religious and cultural freedom to Syria’s diverse communities. The question is whether this will continue. According to anti-Assad and pro-HTS commentators, most Syrians want a secular, democratic and religiously diverse society. Will their desires be met?

A new constitution will take time to frame and elections are a long way off. What accountability is there then for the country’s new leadership? One option that the international community has available is that of sanctions which were imposed on the Assad regime because of its crushing of the “Arab Spring” in 2011 and in the events that followed. It should be made clear to the new rulers, who have little experience of democracy, that sanctions will not be lifted unless there is demonstrable respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms such as freedom of belief, expression and religion, certified by the UN Human Rights Council and other international fora.

Maaloula and Suqaylabiah may well be the “canaries in the mine,” alerting us to the dangers facing ethnic and religious minorities in the new Syria. Even a fragment of what happened in Iraq with IS and the Taliban in Afghanistan should not be allowed to happen in Syria for the sake of all its people and for stability in the region and beyond.