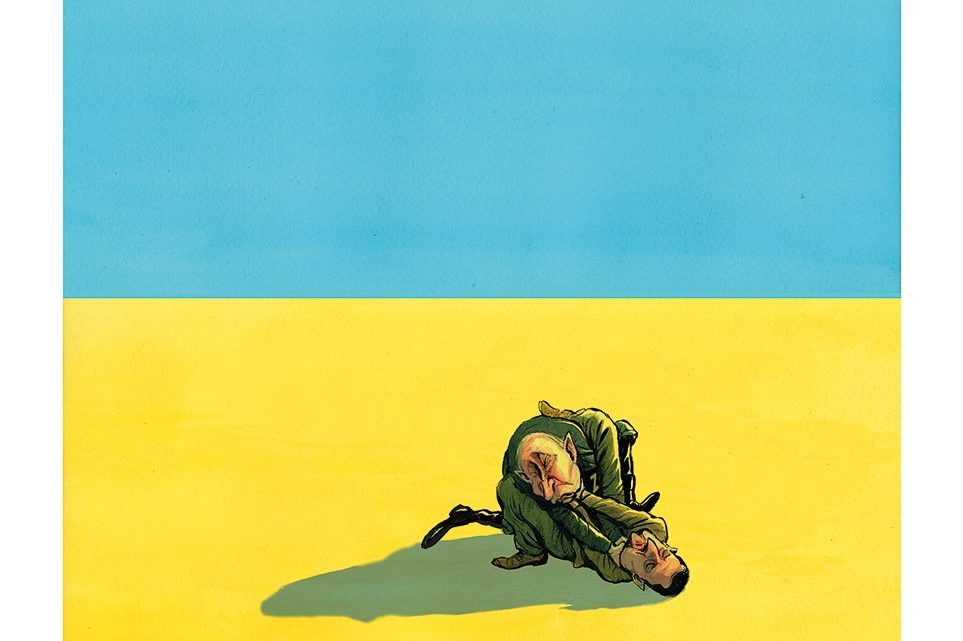

As Ukraine marked its thirty-second national anniversary since independence, news from the front lines and the wider world appeared better than perhaps in any week since the recapture of Kherson in November.

In Zaporizhzhia, the hard-fought front lines moved a few miles forward. In Crimea, a missile strike took out a Russian S-400 anti-aircraft complex and a team of Ukrainian commandos briefly raised their yellow-and-blue flag on the peninsula for the first time since Russia’s 2014 annexation. A Russian Mi-8 helicopter pilot defected to Ukraine with a load of jet engine parts. Near-nightly waves of drone strikes deep inside Russia blew up two Tu-22M long-range bombers, four Il-78 transport aircraft and repeatedly struck central Moscow.

Less than 45 percent of Americans say that Congress should authorize additional funding for Ukraine

Vladimir Putin, unable to travel because of an International Criminal Court arrest warrant, was humiliatingly forced to appear at the BRICS summit in South Africa by video link. The Netherlands, Norway and Denmark announced the transfer of seventy-three F-16 fighter jets to Kyiv. A much-anticipated Russian unmanned landing on the moon ended in disaster, while a rival mission from India succeeded. To top it all, Russia’s most high-profile attack of the week was against its own side: the plane carrying Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin and the whole mercenary group’s leadership blew up north of Moscow with no survivors.

Small wonder, then, that many Ukrainians dared to hope that the tide of the war could finally be turning in their favor. As one Ukrainian artist friend told me on a video call as he strolled past a display of wrecked Russian armor laid out along Kyiv’s main boulevard: “We’re finally getting some breaks… it feels like victory will come soon.” For Mykhailo Podolyak, a senior advisor to Volodymyr Zelensky, Prigozhin’s apparent murder “confirms that a new stage has begun in Russia’s domestic policy… a time of troubles.” He also predicts that Ukraine will not have to “take back every kilometer with blood” because a major breakthrough to the Crimean border will trigger a Russian military collapse. “Everything will end quickly and instantly, just as it began.”

Perhaps. But for the time being, the pace of Ukraine’s advance is dictated first and foremost by the quantity and quality of weaponry supplied by Kyiv’s allies — primarily, the Americans. And clouds are gathering for Kyiv on the US political horizon. A recent CNN poll showed that less than 45 percent of Americans say that Congress should authorize additional funding for Ukraine, against 55 percent who want it to stop.

Donald Trump, the clear leader in the race for the Republican presidential nomination, has promised to end the war “in twenty-four hours.” Pressed last month to elaborate, he revealed his plan: “Tell Zelensky, ‘No more, you gotta make a deal,’ and Putin, ‘If you don’t make a deal, we’re gonna give them a lot. We’re gonna give more than they ever got.’”

This is exactly the kind of land-for-peace compromise Zelensky has repeatedly rejected. Trump’s main Republican challenger (and mooted running mate), the pharmaceutical billionaire Vivek Ramaswamy, is even more Ukraine-skeptic. He says Russia could keep large swaths of Ukraine in exchange for Putin “ending its alliance with China… Our goal should not be for Putin to lose.”

And the Democrats? Joe Biden and his administration have been steadfast in their support for Kyiv. The president repeated last week that the US will “never give up” its support. To date he has pushed $135 billion worth of military and economic aid through Congress. But even Biden’s stated position is to arm Ukraine to “fight on the battlefield and be in the strongest possible position at the negotiating table.” That is very far from Zelensky’s stated goal of liberating all of his lost territories.

Support for continuing to arm Ukraine is generally stronger in Europe, but the numbers are also falling. Germany’s second-most popular party, the AfD, is strongly against the war’s continuation. A four-year, €50 billion EU package of mostly economic and reconstruction aid to Ukraine has run into serious opposition from Hungary, Austria, Croatia, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Slovakia and Greece — and even staunch allies of Kyiv like Poland want more compensation for their own war-related economic problems.

Even the much-heralded Dutch-Danish-Norwegian pledge of F-16 fighter jets is not quite the breakthrough it first seemed. According to reports, at least eighteen of the Netherlands’ forty pledged planes are unable to fly and good only for ground training and parts. It will also take up to eighteen months to train Ukrainian pilots and ground crews and deploy the aircraft to the front lines. But in terms of purely military aid, Europe’s contribution is a mere drop in the bucket compared with the US. The UK, for instance, has provided £4.6 billion ($5.8 billion) of arms to Ukraine — less than 5 percent of the US’s contribution. It is in America that a Ukrainian victory will be broken or made.

With the very real possibility of a new Trump administration being elected in November 2024, the obvious strategy for Putin is to sit tight and hold on to as much Ukrainian ground as he can. “I don’t understand why Putin would end his invasion until he knows the outcome of the US presidential election,” says Michael McFaul, Barack Obama’s chief Russia advisor and former ambassador to Moscow. “Explain to me your plan for getting him to negotiate now.” Only a humiliating, comprehensive and decisive military defeat or a collapse of the Russian economy could force Putin into talks before then.

Realistically, neither of those outcomes seems very likely. While sanctions have poisoned Russia’s economy and depressed the ruble, the Kremlin has managed to keep enough oil exports flowing out, and parallel imports flowing in, to cushion the population from serious pain. Wagner’s mutiny in June showed that Putin’s security state was unexpectedly brittle — but through a combination of guile and treachery Putin faced down, and ultimately eliminated, Prigozhin. Ukrainian drone strikes have brought the war home to millions of Russians who had until now been able to successfully ignore it. However, Kyiv’s attacks inside Russia have so far delivered more symbolic damage than military hammer-blows.

The reality is that Ukraine’s closest allies hold out little hope that Kyiv will be able to achieve what it defines as victory with the military resources that it’s so far been given. A slew of leading US papers, all citing senior administration, military and security sources, has gloomily predicted that Ukraine’s summer offensive is going nowhere. According to one anonymously sourced story in the New York Times: “US and other western officials say Ukraine’s counteroffensive would not have enough decisive firepower to reclaim much of the 20 percent of the country that Russia occupies.” In short, Kyiv’s friends in the West do not seem to believe that Ukraine can win. And the reason the Ukrainians cannot win is the West’s hesitancy in escalating arms deliveries for fear of provoking Putin. The argument is circular.

Support for continuing to arm Ukraine in the US is not only waning but, fatally for Kyiv, is also becoming a wedge partisan issue. As the US enters its 2024 primary and electoral cycle, it seems unlikely that the Biden administration will risk a dramatic increase or upgrade in military aid — and indeed will struggle in Congress to maintain current levels.

That’s unfortunate, it’s tragic and it’s unfair. But the cruel bottom line is that it’s now down to the imagination and fighting spirit of Ukraine to try to win as much ground as it can with the resources that it has before war fatigue among its allies cheats it of victory.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.