‘We swore to defend the constitution,’ shouted the deputy speaker of the Tunisian parliament, to which a young soldier retorted, ‘We swore to defend the fatherland’.

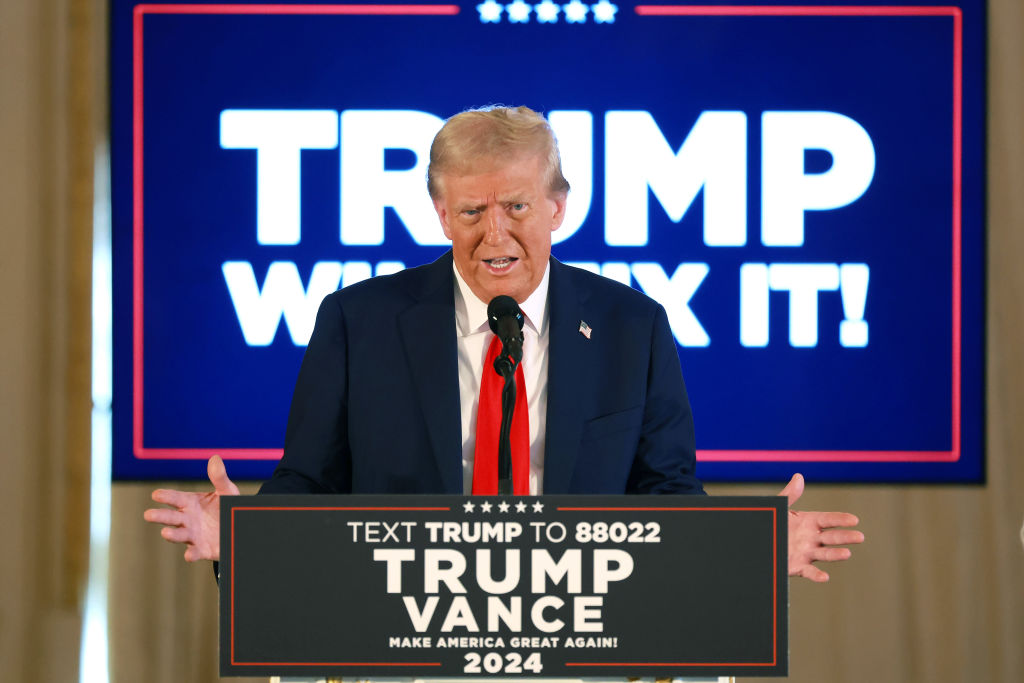

This exchange in front of the locked gates of parliament last month sums up the paradox of Tunisia. President Kais Saied’s decision a few hours earlier to dismiss his government and suspend parliament had enraged the Islamist speaker and his deputy, who sought to enter the building now guarded by armed troops.

Yet tens of thousands from every social class poured into the streets of Tunisian towns and villages, shouting their support for Saied. That support has remained rock solid over a month later, despite the condemnation of what many western commentators called a coup against democracy.

Diplomats in Tunis were mostly caught unaware, having seriously underestimated the tactical skills of the dour, socially conservative law professor. Saied has few advisers and speaks only to condemn, in the most vigorous terms, the gangrenous corruption that is destroying his once prosperous North African country. Tunisia was the first Middle Eastern country to topple its dictator a decade ago, the spark that lit the conflagration of revolts that engulfed the Arab world.

Despite the shock of western observers, few in the country itself were surprised by the president’s decision. Financial indicators have been flashing red for years and Tunisia will go bankrupt this fall if it fails to negotiate a bailout with the International Monetary Fund. Playing cat and mouse with Tunisia’s foreign creditors was the hallmark of the now-dismissed prime minister, a modern version of fiddling while Rome — or in this case Carthage — burns. Democracy has taken the form of a souk, a clearing house for deals between different economic and political lobbies, not to mention the mafias whose power has grown beyond that of the country’s sickly institutions.

One example above all illustrates the utter incompetence of Tunisia’s last government. By July, the escalating COVID-19 crisis had claimed the lives of over 20,000 Tunisians. The respected Institut Pasteur (est. 1893) and Tunis’s private pharmaceutical companies had the capacity to manufacture vaccines. And yet an offer by Pfizer to manufacture vaccines, made last winter, went unanswered. For many doctors, such behavior is not just incompetent but criminal.

Ever since the jasmine revolution of 2011, successive Tunisian prime ministers have fallen prey to what one economist describes as ‘magical economic thinking’. The payroll of the civil service and state companies has increased by more than 150,000 to over 600,000 in a country of under 12 million souls. Many were recruited without any qualifications, often with no obligation to turn up to work.

Most political parties, business interests and mafias have been party to this game, hollowing out what was once one of the better Arab civil services. Tunisia’s public wage bill consumed about 75 per cent of tax revenues in 2020, up from 53 percent in 2010. The inevitable consequence is that investment in infrastructure, education and health has been slashed. As thousands of doctors flee the country, hospitals have buckled under the strain of a badly handled pandemic. Yet since Saied ordered the army to take control of vaccination, an estimated 1.5 million people have received their first shot.

In the past five weeks, the police have, on orders of the president, raided warehouses across the country, confiscating huge amounts of undeclared goods; most smuggled through ports where customs no longer operate but are instead run by one of the countless mafia groups. Many goods come from Turkey, a strong supporter and many suspect financier of the Islamist party Ennahda, a parliamentary pillar of every government since 2012.

The US and the EU need to offer Tunisia, through bilateral trade and the IMF, a generous package. They failed to do so in 2011 when their policy in Libya threw hundreds of thousands into the Mediterranean and down into Africa.

Constitutional and electoral reform are both essential but cannot be willed by fiat. Hence the support for the president is tinged with apprehension, lest this morally rigid man think himself a savior who can singlehandedly resurrect prosperity. Saied is ignorant of economic matters. His dislike of money is no substitute for a sound economic policy and the encouragement of genuine entrepreneurs. Redistributing the spoils of corruption will not create jobs. As suspicious as he is of politicians, senior servants of the state and businessmen, Saied is going to have to pick out those of integrity to help rebuild the country’s institutions.

The role of the army will be key. Small and professional, it is atypical among its Arab peers. It has never played a political role and has no business interests. Its senior officers are trained by the US, which has played a central role in helping Tunisia fight terrorism. The military has acted as the guarantor of the fatherland but it has no desire to run it.

Democracy is often associated with prosperity. That is the cultural mantra repeated by the West. Is democracy sustainable if poverty, corruption and incompetence capture a society? The answer might not be the one we like. Hence the hope of most Tunisians that Saied can find a way out of the impasse. Rome was not built in a day and neither will democracy on the Carthaginian shores.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.