Whatever loopiness there is in Donald Trump’s personality is a loopiness born of isolation. For ten years the history of the world has revolved around him, not he around it. The events of last November have left Trump as, for all intents and purposes, the only remaining historical actor – especially after Xi Jinping’s retreat into obscurantism since the pandemic.

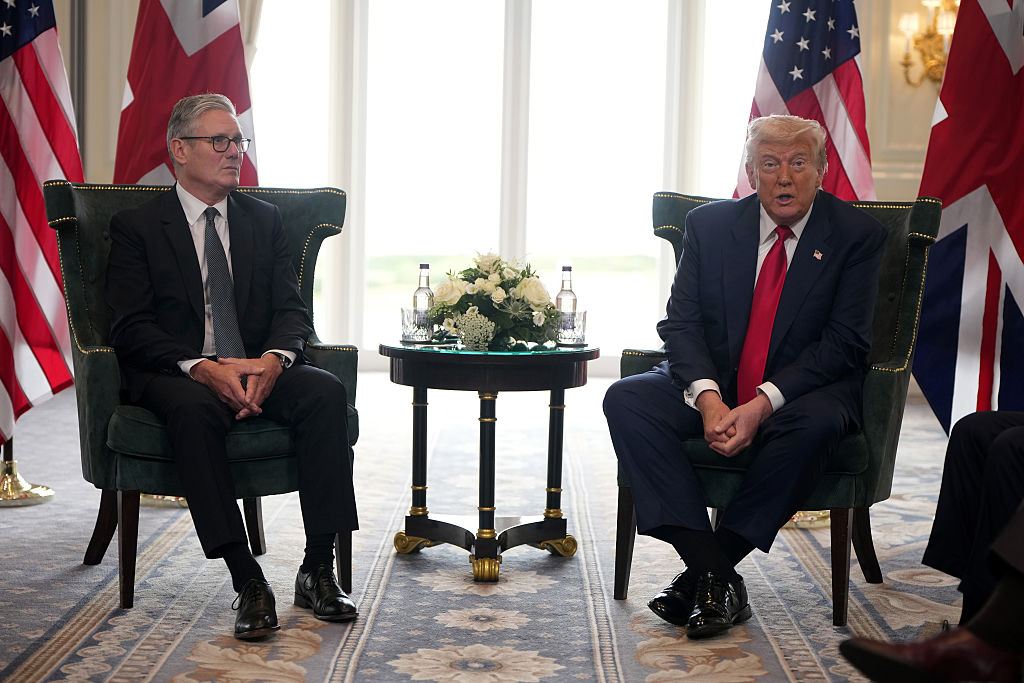

Trump’s worldview has never been much of a mystery but yesterday, at his Turnberry golf course in Ayrshire, Scotland, he gave the assembled a new précis:

“Politics is pretty simple… Whoever does these things: Low taxes, keep us safe, keep us out of wars, no crime, stop the crime, and in your case, a big immigration component… The one that’s toughest and most competent on immigration is going to win the election”

His guest, Britain’s premier Keir Starmer, looked blinkingly on. Billed just over a year ago as the natural leader of the global resistance to populism, Sir Keir has as of 2025 at least rhetorically committed himself to almost this exact agenda. His latest court theorist, Baron Maurice Glasman, is a longtime pen pal of Vice President JD Vance.

World politics has now reached an odd stage where the Trump agenda is fast becoming the consensus but in which people still find obscure reasons to oppose him.

In 2025 no one really defends irregular migration, at least not on principled “no human is illegal” grounds. Immigration is still happening at scale but is only justified by expediency while overt celebrations of diversity rapidly go extinct. There is a well-established liberal narrative of Woke excess from 2020-24. When people now look back at lockdown they wince, and wonder why we couldn’t have been a bit more like Sweden.

Most now know that there needs to be some reform to the state machinery of Western democracies, which do not work, and that attempts to do so are not in fact a prelude to dictatorship. Most acknowledge also that it seems impossible to build things such as housing or railways anymore, and that overmighty judicial review and environmental audit may have something to do with it – an old Trump line of ten years vintage.

Almost everyone accepts that Russia will not be driven out of its captured provinces and that the aim now is an honorable peace that the Ukrainians can live with. Old social media posts calling for police abolition are silently deleted.

What, then, is the actual content of disagreement? Why are we still meant to be living through a struggle between populism and the establishment when the substance of it has largely been conceded?

It is often difficult to say. Some of the reasons are personal, some national, some symbolic; none add up to a unified view of the world that opposes something like Trumpism on principle.

Anti-populism is increasingly spinning off into a series of local particularisms with no grand narrative. Mark Carney became Canada’s prime minister off the threat of annexation, an establishment victory but one obviously not replicable at scale. He has since introduced deep cuts to legal immigration. Other figures such as Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese got a new wind from Trump’s tariffs but, again, the issue is sectional rather than one of principle – people like Albanese were perfectly willing to collapse global trade over Covid-19 five years ago.

For others it is a case of simple dissonance. Leaders loudly commit themselves to Trump-style reforms only to balk at the means. One perennial feature of the last ten years has been moderate Democrats opposing the idea of an open border but denouncing any methods by which it might be policed. Keir Starmer now accuses Britain’s civil service of being “comfortable in the tepid bath of managed decline” but is unwilling to change any of their processes or trim their numbers even slightly. Denmark’s rulers talk tough on illegal immigration but are still horrorized by simple practicalities like family separation: the politician Inger Støjberg – in an extraordinary step – was deprived of her seat in parliament and jailed over the issue.

Characteristic of this era have been figures who seem to exist between worlds. These are people who are attached to, if not the content of the antebellum era, then at least to its forms. One example is Downing Street’s previous incumbent Rishi Sunak, who staked his premiership on the pledge to “stop the boats” of illegal migrants crossing the English Channel but could never bring himself to exit the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), which alone would’ve made deportations possible. Demagogic rhetoric against illegal aliens was fine; the largely symbolic step of ECHR exit still too much. The ostensible neo-fascist Giorgio Meloni of Italy, now hailed as a pillar of the European establishment, is another.

Local objections and wrangling over means may yet weigh the MAGA agenda down, Lilliputian style. But what’s striking is the collapse of any unified theory as to why something like Trumpism is wrong. Most online criticisms of the 47th president only allege that he is failing on his own terms: that he is not non-interventionist enough; that deportations are supposedly down compared to the Biden and Obama years; that he is not spilling the beans fast enough on Epstein. Even on the latter point elite opinion is converging on the Trump view: that they know something was fishy about the affair but are unwilling to handle the detonation of the Anglo-American establishment that a full disclosure would mean.

Taken together, the real point of conflict in 2025 is that Trump is the only leader willing to act on the conclusions that most people have now reached. That administrative reform might mean firing people. That border control might mean some upsetting footage of arrests. That ‘YIMBY’ism to make building things such as data centers easier might mean trimming the powers of judges. More and more are drawn into his orbit, but his isolation continues.

Leave a Reply