Over the weekend, President Donald Trump described his sweeping 10 percent tariffs against Chinese goods as an “opening salvo.” Within minutes of them taking effect at midnight last night, Beijing retaliated with targeted tariffs of its own against US coal, liquified natural gas (LNG), farm equipment and cars. It also announced export controls on a string of critical minerals to “safeguard national security” and what it described as an “anti-trust” investigation into Google. Like most Western internet and social media firms, Google is already banned from China, but earns money from Chinese businesses advertising abroad.

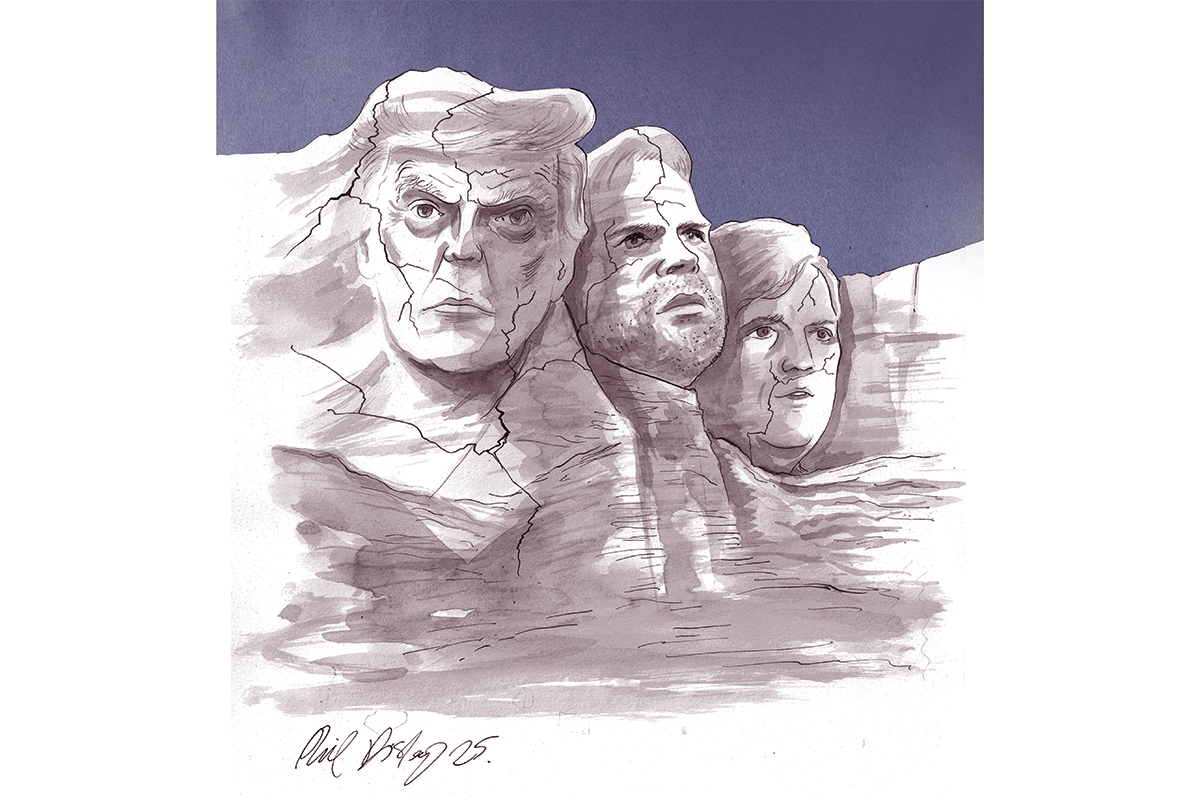

The president has described tariffs as ‘the most beautiful word’

In spite of the “trade war” headlines, stock markets and many analysts are surprisingly sanguine. China’s measures are “fairly modest, at least relative to US moves, and have been calibrated to send a message to the US,” said Julian Evans-Pritchard, the head of China Economics in a note. China’s tariffs targeted some $14 billion of American goods, according to analysts at Citi Bank, or less than 10 percent of total imports from the US in 2023. Furthermore, Trump plans to speak with President Xi Jinping later this week, according to the White House, raising hopes that, as with the pausing of tariffs against Mexico and Canada, some sort of deal can be done to rein them back.

That may be wishful thinking. In justifying his latest tariffs, Trump cited China’s role as a supplier of precursor chemicals to Mexican drug gangs for the manufacture of fentanyl, a deadly opioid that kills tens of thousands of Americans every year. Beijing has described the crisis as America’s problem, though did take some action last year, cracking down on money laundering linked to the trade. This, however, was not nearly enough for Trump. “China hopefully is going to stop sending us fentanyl, and if they’re not, the tariffs are going to go substantially higher,” the president said on Monday.

But even if Xi makes the right noises on fentanyl, there is little or no trust that China can ever be taken at its word. There is a widespread belief in Washington that China has gamed the international trade system at every turn, that there has never been a level playing field for western businesses in China, and that its rise has been facilitated by the systematic bending and breaking of just about every agreed-upon rule of international commerce as well as the widespread theft of technology. Add to that the growing geopolitical tensions and escalating tech war — where AI is the most visible battlefield — and the prospects of a serious tariff truce are not good.

China is aware of this, and has been preparing its defenses for some time. Late last year, it restricted sales to the US of other key minerals, where Beijing substantially controls supply chains. These included gallium and germanium, which are used in semiconductors, infrared technology, fiber optic cables and solar cells. China’s commerce ministry also ordered closer scrutiny of the export of graphite, a key component of electric vehicle batteries, the processing of which is also a near Chinese monopoly.

It has also begun to limit sales to the US and Europe of key components used to build drones and threatening to add more American companies to what it calls its “unreliable entity list.” These include PVH, which owns the Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger brands, which has a significant presence in China, and is being investigated for “boycotting Xinjiang cotton and other products without any factual basis,” according to the commerce ministry. Western clothing brands have come under pressure from their own governments to police their supply chains to see they are free from forced labor, a move the CCP describes as “discriminatory.”

“De-risking” is a term usually applied to western companies shifting their supply chains away from China, but Chinese companies themselves have become some of the biggest “de-riskers” from their own country. There has been heavy Chinese investment in Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand in particular (and of course Mexico) as a way of side-stepping tariffs. This takes on many forms, but much of the new investment comprises the assembly of imported Chinese components or the re-labeling of “made in China” as goods made elsewhere.

The Malay and Thai authorities are increasingly worried about getting caught up in the US-China trade war, vowing to stop their countries being used to transship China-made goods. “We have made preparations to deal with more imports from China,” said Theerat Atthanawanit, the Thai customs director-general, in December. Meanwhile, Malaysia’s deputy trade minister Liew Chin Tong said, “I have been advising many businesses from China not to invest in Malaysia if they were merely thinking of rebadging their products via Malaysia to avoid US tariffs.”

Chinese solar panel companies have become particularly adept at this, shifting across southeast Asia. They have come in for particularly close scrutiny by the US authorities for muddying the origin of panels that attract a 50 percent tariff if made in China and frequently source polysilicon from Xinjiang, where there is evidence of forced labor.

It is not clear what the Chinese authorities themselves make of this exodus, since it has resulted in a net outflow of foreign direct investment from the country. There have been reports of Chinese customs tightening their scrutiny of exports by Apple and other American tech giants of production equipment and materials to Vietnam and India in a bid to slow down their supply chain diversification.

Apple, together with Tesla, are perhaps the highest-profile American investors in China, both relying heavily on the country as a market and a manufacturing base. There has been speculation that they could become targets in an intensifying trade war. That’s unlikely in the short term since both have brought significant technological benefits to China. Tim Cook and Elon Musk are cheerleaders for Chinese engagement and will be regarded by the Chinese Communist Party as important assets — at least for now.

All of this makes for an intriguing backdrop to the latest tit-for-tat tariffs. The president has described tariffs as “the most beautiful word” and we may be witnessing the start of a new “great game” of levies. It might also bring about tariff avoidance and supply chain shifts, with Beijing in particular playing for the potential geopolitical benefits that might accrue should Trump alienate his allies. If the president is serious, his tariff crusade could at the very least turn into a giant game of whack-a-mole that could quickly get very messy.