One of Donald Trump’s 2024 campaign ads was aimed at Jewish voters. Three stereotypical New York bubbes are kvetching about the state of the world. “Israel’s under attack. Antisemitism like I never thought I would see.” One says: “Oy vey… You know Trump I never cared for, but at least he will keep us safe.” This was a canny appeal, recognizing that many American Jews were traditionally Democrats and would have to hold their noses to vote for Trump. But Trump has been — as he says himself — Israel’s “protector” and Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, was the first foreign leader to praise him for his victory: “Congratulations on history’s greatest comeback!”

Netanyahu signed off his message to Trump “in true friendship.” In truth the two have a difficult history. They didn’t speak for almost four years after Netanyahu recognized Joe Biden’s win in 2020. In April, Trump made a number of digs at Bibi to TIME magazine. He blamed him for the October 7 massacre and said the Israeli leader had backed out of what was supposed to be a joint operation to assassinate the Iranian general Qasem Soleimani (“That was something I never forgot”). Not a stand-up guy, not loyal — the worst thing you can be in Trumpworld.

They patched things up over the summer when Bibi visited Mar-a-Lago, all smiles and hugs by the pool. Trump later told one of his rallies that Netanyahu was calling him almost daily for advice. He said Israel should “finish the problem” in the war against Hamas. He reveled in the pager attacks on Hezbollah. All this is a reminder of how Trump was the American president who recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, who moved the US embassy there and who ended the Iran nuclear deal. But Trump is also, famously, transactional and American military support for Israel reportedly cost $23 billion last year. He is also instinctively an isolationist and might, this time, bring enough loyalists into government to face down America’s interventionist foreign policy establishment. Above all, he is a dealmaker — and this is where the danger to Netanyahu lies.

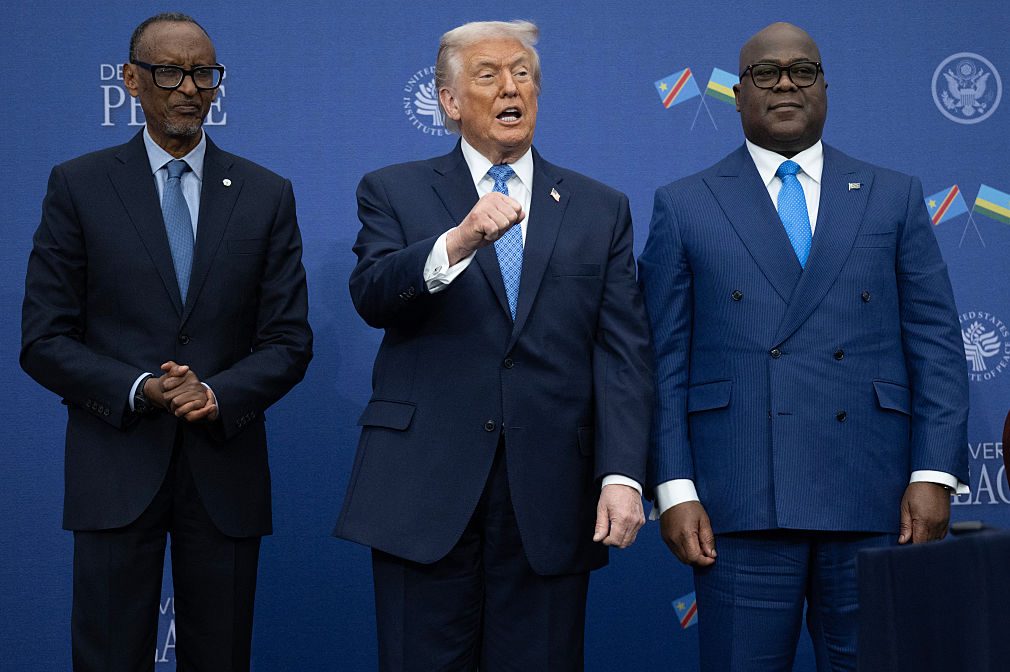

One of the greatest and most unexpected diplomatic triumphs of Trump’s presidency was the Abraham Accords. Trump had told his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, to go and make peace in the Middle East. To everyone’s surprise, Kushner came back with a deal for the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain to recognize Israel. (It might have helped that Kushner was being tutored by Henry Kissinger.) The next logical step is for Saudi Arabia, too, to formally make peace with Israel. They were edging towards an agreement before October 7. Now, though, the Saudi price for a deal is the creation of a Palestinian state — something Netanyahu has spent his entire career trying to stop.

Kushner and his wife, Ivanka Trump, have said they won’t return to the White House, too busy becoming billionaires as Kushner’s investment fund is showered with cash. But while Kushner had no formal role in his father-in-law’s election campaign, he was reportedly active behind the scenes.

Could Trump call on him to work informally again, as a backchannel to the Saudi leader? That informal role might suit Kushner. When Trump left office, Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) gave $2 billion to Kushner’s fund. Staying out of office makes it much easier to accept these payments.

Kushner and MbS always had a warm rapport. But getting MbS to drop the demand for a Palestinian state will be hard. In September, the crown prince appeared to strengthen his position, saying a Palestinian state is a condition of any peace agreement.

This is necessary rhetoric for an authoritarian Sunni ruler keeping one eye on the Arab street, which has been inflamed by images of children’s corpses in Gaza and Lebanon. But the Saudi royal family are ruthless in pursuit of their own interests and Kushner — or some other envoy — will have the strongest possible card to play: the promise of a new defense pact with the US.

Such an agreement is probably only possible as part of a deal for normalization of Saudi-Israel relations. Otherwise even a Republican Senate would find it difficult to ratify yet another US military commitment. The Saudis might be persuaded to agree to some halfway house: a roadmap to a sovereign Palestinian state rather than its actual establishment. This is because the Middle East is on the brink of a catastrophic war that could ignite the whole region.

The path to a wider war is clear. Iran and Israel are locked into an escalatory cycle. In October, Iran fired 180 ballistic missiles at Israel. Israel responded with precise and effective strikes on military installations, almost completely destroying Iranian air defenses. The response to the response has yet to come, but senior Iranian officials have been quoted as saying it will be “harsh” and “unimaginable.” This is standard rhetoric, but Iran’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, may feel he has to order some- thing credible to avoid admitting defeat. Israel could then expand the war to hit oil facilities and Iran’s nuclear program.

The wider Middle East war might be raging by the time Trump takes office. Trump might feel the US should come into the war on Israel’s side (if that isn’t already happening by the time he swears the oath). It was unwise of Iran — if true, as claimed — to run a covert influence operation to hurt Trump in the election. But Trump would also love to get out of the region altogether. He once said that “the single worst decision our country ever made” was to go into the Middle East.

Trump is mercurial and it’s hard to tell what he will do next. The next four years are going to be a wild ride for leaders in the Middle East and everywhere else. But if there’s a consistent theme, it is that he is no warmonger. He has spoken of his wish to end the multiple conflicts in the Middle East once and for all, and not, as he has said, to have to come back to the region every five or ten years. That would be the deal of the century and if it means a Palestinian state, Netanyahu will discover the truth of Palmerston’s saying that nations have no eternal allies, only interests.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply