This article is in

The Spectator’s November 2019 US edition. Subscribe here.

Elizabeth Warren looks like a deadly serious prospect for the Democratic presidential nomination. Bernie Sanders may never make it to that promised land, but there is no question that his spirit is still moving the Democrats toward democratic socialism. The party’s activist base and youth wing grow more anti-capitalist by the month. It’s enough to turn many a libertarian or Chamber of Commerce conservative into a Trump supporter, despite the president’s own defiance of free-market orthodoxy on trade.

Yet the president might as well be Milton Friedman compared with some on the right who are, if anything, outflanking the left in their critiques of capitalism. ‘The main threat to your ability to live your life as you choose does not come from the government any more,’ Tucker Carlson told the National Conservatism Conference in Washington, DC last July, ‘but it comes from the private sector.’ Sen. Josh Hawley, a Missouri Republican, and the editors of First Things have likewise taken aim at corporate America, particularly the tech sector. These conservatives are as likely as Sen. Warren to espy virtues in a wealth tax.

Socialists to the left, nationalists to the right — these are daunting times for defenders of capitalism. This year was the 75th anniversary of the publication of Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, and the Austrian economist’s admirers could be forgiven for thinking his book’s lessons have gone unlearned.

But Hayek himself might rethink that judgment in light of everything that’s happened since 1944, when he warned that even a little socialism and central planning would lead to a lot more. Since then, what has become obvious is that there is simply no stopping commerce. Far from being a delicate flower easily crushed by careless would-be gardeners, capitalism is robust, even to the point of being weed-like.

Lenin had already discovered by 1921 that ‘full communism’ wouldn’t work even with the power of a totalitarian state behind it, a reality that compelled him to adopt what was called the ‘New Economic Policy’. It restored a small degree of private enterprise within the Soviet system. The USSR’s participation in international trade was another link — a lifeline — to the real world of prices set by demand and availability rather than by party bureaucrats. And of course, the Soviet Union had a thriving black market, in some respects the freest kind of market of all.

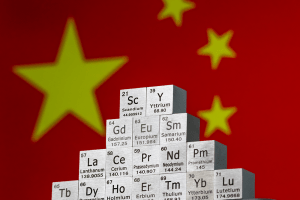

The Soviets tried to the bitter end to minimize the power of market forces within Russia and its empire, with results that are celebrated now in the memory of the Berlin Wall’s demolition and the collapse of the USSR itself. The other communist superpower of the 20th century, the People’s Republic of China, remains with us to this day, but only as a result of having adopted capitalist reforms and harnessing the ensuing prosperity. Yet therein lies an ugly truth: capitalism as an economic system has proved to be quite compatible with despotism as a political system. This should not surprise us. Even in Europe capitalism once existed alongside absolutism.

Commerce has been a commanding influence on western civilization since the Middle Ages. It was in quest of commodities that Portugal and Spain blazed their way around Africa to India and across the Atlantic to the Americas. The earliest English settlers in North America came as colonists of the profit- seeking Virginia and Plymouth Companies. A decade before the Revolutionary War, the independence of Britain’s American colonies was foreshadowed by their eagerness to trade with His Majesty’s enemies during the French and Indian Wars.

The variety of US wars that have been fought for territorial expansion (which is also commercial expansion), market ‘openness’ and the upholding of a trade- oriented ‘liberal international order’ would be embarrassing, if not for the unceasing efforts of journalists and academics to disguise more recent conflicts as exercises in sheer altruism.

The great Anglo-Celtic minds of the late 18th century — such as David Hume, Adam Smith and indeed Edmund Burke — tried to humanize the struggle for markets and goods by showing how cooperation could achieve more than war and the brutal ways of the British East India Company.

They only partly succeeded: today wars are still fought over access to and ownership of goods, but access and ownership are understood as features of a market system, rather than merely as the interests of a nation or company. There is a need to rehumanize capitalism, now that liberalism has become a hypocritical dogma. Nationalism is the way to do it.

Trump’s economic nationalism has been an effort to save capitalism, not to bury it — to prove it can still work for a free America and not just for a despotic China, and that it can serve Americans of all regions and economic levels and not just the investor class.

This, rather than a rehash of the 20th century’s clash between communism and free markets, is the conflict of our time. Capitalism will triumph again whether the next century is Chinese or American. But capitalism without Smith and Burke and the best of the Anglo-Celtic tradition America inherited will look more like it did in the 17th century and earlier, when trade wars were shooting wars, states sponsored privateers and companies indulged in colonialism and worse.

Liberalism cannot save capitalism with western characteristics because liberalism has become both illiberal and anti-western. What is needed now is for America and the West to harness capitalism as successfully as China has, in the service of our civilization and our way of life. Of all our great institutions — family, faith, citizenship, representative government — free markets are the least endangered. They should be a source of strength to the rest: our civilization’s fate depends on it.

This article is in The Spectator’s November 2019 US edition. Subscribe here.