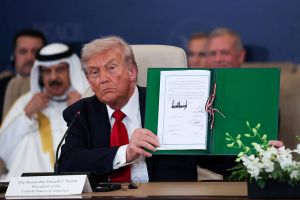

Donald Trump is a master of the obvious. This is why his foreign policy keeps surprising the status quo powers of American politics: the media, the bureaucrats, and the elected officials. Today, these wise monkeys are reeling at the news that Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps is a ‘foreign terrorist group’, and that the IRGC ‘actively participates in, finances, and promotes terrorism as a tool of statecraft’.

Here’s something else that’s obvious. Since 9/11, the United States has staggered from one fiasco to another in the Middle East: the invasion of Iraq, the endorsement of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, the trashing of Libya, the incoherent response to the Syrian civil war, the humiliation of an effort to get out of the region through the ‘Iran Deal’. When the mullahs in Tehran decry US foreign policy as ‘global arrogance’, they’re only stating the obvious too.

Obviously, the people for whom no US government can do anything right disapprove of Trump’s decision. Prominent in the first pack of Twitter critics was that hot-thumbed nitwit Glenn Greenwald. ‘Trump’s designation of IRGC is stupid, dangerous & provocative, making it much harder to forge a peace with Iran,’ Greenwald tweeted today. ‘You can’t arm and hug Saudis while pretending to oppose terrorism.’

As Glenn says every time he drags his luggage into his apartment in Rio, let’s unpack that a little further. It is Saudi military forces, not Saudi terrorist groups, that are waging a brutal and clumsy war in Yemen. It was the IRGC’s terrorist proxies, trained in Iran by the IRGC and armed with Iranian plastic explosives, who killed so many US and UK soldiers with IEDs in Iraq. That was a dangerous and provocative thing of the IRGC to do, and it was stupid of US administrations to look the other way.

More serious objections to Trump’s decision turn on tactics and timing. Here, I differ once again with my fellow opinionator Jacob Heilbrunn. Jacob suspects that Trump’s Middle Eastern policy has been ‘captured by a neocon contingent’ from the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. I suspect that Trump doesn’t have a Middle Eastern policy, so much as the principle, radical in recent American foreign policy, that a great power has interests, not friends, and that you reward those who serve your interests and punish those who don’t. It is his refusal to be taken for a fool that impels Trump to state the obvious, instead of repeating whatever diplomatic fictions the State Department slips onto his teleprompter. I also suspect that the only person to whom Trump subordinates his opinions is his strong-thighed Slovenian mate. But that is a matter of domestic policy.

Jacob is right to observe that the timing of Trump’s announcement aids Benjamin Netanyahu’s campaign for re-election, and bolsters the Israelis and Saudis in their anti-Iranian campaign. So much the better. Netanyahu lacks charm and, it appears, principle. He also represents stability and competence, qualities that a serious power needs from its client states. These qualities are in increasingly short supply in the region. It’s unclear whether Netanyahu’s neophyte challenger Benjamin Gantz possesses them. Better the Benjamin you know.

Here we see a hidden continuity between the Obama and Trump administrations. The US is a status quo power in the Middle East, committed to the paradox of maintaining its regional influence while reducing its military footprint. The only way to reconcile these goals is to outsource the military element. The Obama administration’s folly was to assume that balancing the Iranian-led Shi’ite crescent against Israel and the Sunni powers was a recipe for stability, as opposed to a nuclear free-for-all. The Trump administration’s wisdom is to build up the allies of the status quo — Israel, the Saudis, Egypt, Jordan, the Gulf states. There is an obvious logic here, too. Iran is their problem before it is anyone else’s.

But Iran is also everyone else’s problem. Jacob writes that Iran ‘was abiding by the terms of the nuclear deal’ before Trump canceled it. But that was only because the deal failed to include the testing of ballistic missiles, or a polite request that the IRGC didn’t use the deal’s cash dividend to finance terrorism across the region, and beyond too.

Since 1979, the regime in Iran has been committed to global revolution. The United States remains committed to a different, and preferable, view of the world. The making of policy in the fog of ideology or, after 9/11, anger has not served American interests in the Middle East. It has, however, created chaos that the Iranian regime has exploited through the IRGC and proxies like Hezbollah.

It is to Trump’s credit that he has recognized this as obvious. For it is only by recognizing the obvious that the US can formulate policies that have a chance of succeeding — and avoid perpetuating the ever-losing ‘forever war’ that has cost so many American lives, so much American money, and so much American credibility.

Dominic Green is Life & Arts Editor of Spectator USA.