In recent weeks I have been trying out a mental exercise. Perhaps you might join me? Cast your mind back to 1999. We were standing on the dawn of a new millennium. True, there was a strange fear that all the computers might crash because of a bug called Y2K. But aside from that there seemed to be a tremendous optimism. One of the biggest causes for this was the nature of information technology: specifically, the internet.

Imagine if someone had said to you then: “We are heading into a world where almost anything can be read at the click of a mouse. Almost all the great books will be available free online. Almost any quote or reference can be found at the press of a few buttons. Oh and anyone in the world can speak to anyone else, swap information and solve problems. So if you are a physicist in London and another great physicist lives on the other side of the planet, you can do a thing called ‘Skype’ — just remember to unmute yourself.” If you had put this to our younger selves, I fancy we’d have said: “Well, then there is almost nothing we mightn’t solve in the twenty-first century. We could cure all diseases, become an interplanetary species, etc etc.”

Fast-forward to 2023 and we struggle to define what a woman is. And the world’s most powerful democracy is fighting over which year, indeed century, the country was founded. In other words, we have become stupider. Instead of solving problems we have created wholly unnecessary new ones.

In part this seems to be because of something that Henry Kissinger pointed out in these pages nine years ago. In an interview with Andrew Roberts, Kissinger highlighted the differences between information, knowledge and wisdom. In the internet era they get confused. We might have instant access to information, but as Kissinger said: “The more time one spends simply absorbing information, the less time one has to apply wisdom. And then there’s common sense. Lord Salisbury had long periods of reflection in which he applied wisdom and common sense.”

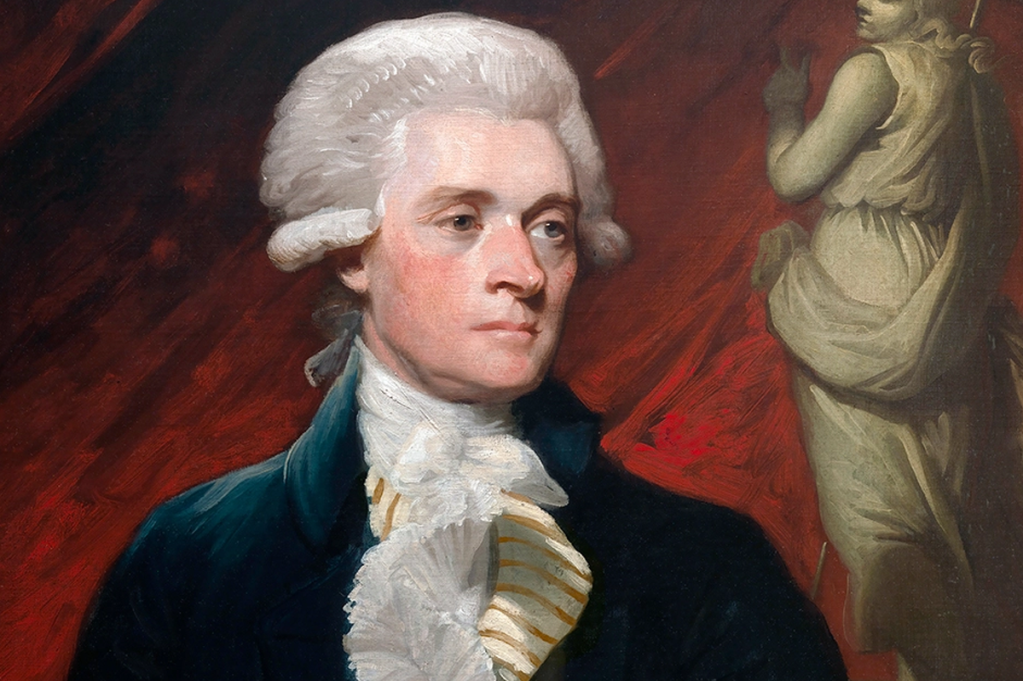

As it happens, I spent last week touring American universities for the Common Sense Society, and as usual when speaking at campuses felt both a certain degree of hope and a considerable amount of dread. The dread comes from the administrators, most of the faculty and many of the students. For instance, I started my week at the University of Virginia. It is one of the many American universities which have serious problems because of their founding — probably the majority do. In this case the University of Virginia has a problem because it was founded by Thomas Jefferson.

Until recent years, being founded by Jefferson — whether in the case of the United States or a university — was a badge of honor. Today it is a mark of Cain. That is because in the 1990s a book by someone called Annette Gordon-Reed popularized the idea that Jefferson had sexual relations with one of the slaves that he inherited from his father. Sally Hemings has since become as close to a historical household name as you can get in America. A commission was set up in the 1990s to look into the issue and members of that commission who I have spoken with have repeatedly — in public and private — expressed their doubts about the DNA evidence the commission investigated.

To get briefly into the weeds, a strain of Jefferson family DNA exists in the descendants of Hemings, and therefore many people concluded that the third president and author of the Declaration of Independence was not just a slave-holder but a slave-rapist. That narrative has become embedded with a furious certainty. Even the custodians of Jefferson’s home at Monticello have adopted it, though are slyly trying to turn the story into a sort of inspiring early interracial romance.

In fact, the DNA evidence simply shows that a member of the Jefferson family had sexual relations with Hemings. And there are at least two ne’er-do-well relatives who seem much more likely suspects. But in modern America, once a negative story about the past comes out, it almost immediately gets mainlined into present-day culture. Statues of Jefferson have been coming down, as have those of almost everybody else, including the leaders of the southern and northern armies in the Civil War. As I found while speaking to students and faculty, an almost insanely context-stripped story is taught about the American founding: that the US was founded in sin (in which case, I ask, what is the original sin of other countries?), that the founders were racists, that America is a racist country today and that as a result no current good can come from it.

Some audience members at the University of Virginia seemed positively furious with me when I cast doubt on the Jefferson narrative. A hundred years ago an American might have fought to defend Jefferson’s honor. Today, many actually want him to be a rapist and are incensed should you demur.

The good news is that the smarter students, while cowed, are finding their way through this maelstrom. The wiser ones recognize that they are not being taught how to think. Some realize their great good luck in inheriting such wonderful institutions. The problem is that there are in turn a dwindling number of people to guide them. I finished my week at Harvard with Harvey Mansfield, now ninety and one of the great American political philosophers of his generation. The author of numerous books, he is the translator of de Tocqueville and Machiavelli, among others, and still teaches a course.

But one can say with certainty that after he is gone he will not be replaced. Harvard, like every other American institution, is filled with dogmatic certainties about past and present. Many faculty and students are filled with information. But where is the wisdom? The ability to see your country’s — even your institution’s — story in a reasonable light? It is dying out. It will be the responsibility of a new generation to give it life again.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.