Jerusalem

I thought I’d found the most efficient small clinic in Jerusalem, a quarter of an hour’s drive from my home. For months, I’ve been going there for testing, with no fuss or waiting time. At the end of last week, the government authorized the third ‘booster’ dose of COVID vaccine for over-forties. I made my appointment for a Sunday afternoon and soon found out how things had changed.

The car park was packed. Inside the clinic, in the corridor leading to the vaccination cubicles, matters were even worse: several people had been given online appointments for third doses for the same time. It’s a far cry from the first vaccine rollout just eight months ago, in which sports stadiums and city squares were converted into mass jabbing centers. But there was a lockdown then, and it was easy to commandeer large public spaces. Israel is now trying to launch another vaccination drive with the country open almost as normal. There’s a big difference.

A few months ago, when the last COVID wave receded, there was a brief illusion that Israel had vaccinated its way to achieving herd immunity. At one point, the number of daily cases fell to single digits. Then came the Delta variant and, for a brief period, denial. There was an unwillingness to accept that Israel, the world’s vaccine success story, could so quickly transform into a world leader in infections per capita.

It would be one thing if COVID was spreading through the unvaccinated. But the Delta variant has made its way through the relatively wealthier, well-jabbed parts of Israeli society: among older people who travel and socialize, according to Professor Doron Gazit, member of a COVID-19 monitoring team at Hebrew University. ‘They were also the ones who had been vaccinated early on, and the protection against infection was waning. Then their children and grandchildren took COVID to school,’ he says.

At first, the government was slow to react because the rise in infections barely translated into a rise in hospitalizations, serious illness or deaths. When those began to rise slowly as well, it was mainly among the small proportion of non-vaccinated adults. Even now, the number of serious cases is still much lower than in the previous wave (of the Kent/UK variant) — but by now, nearly a million and a half booster shots have been given, boosting the immunity of those people who received vaccines early on.

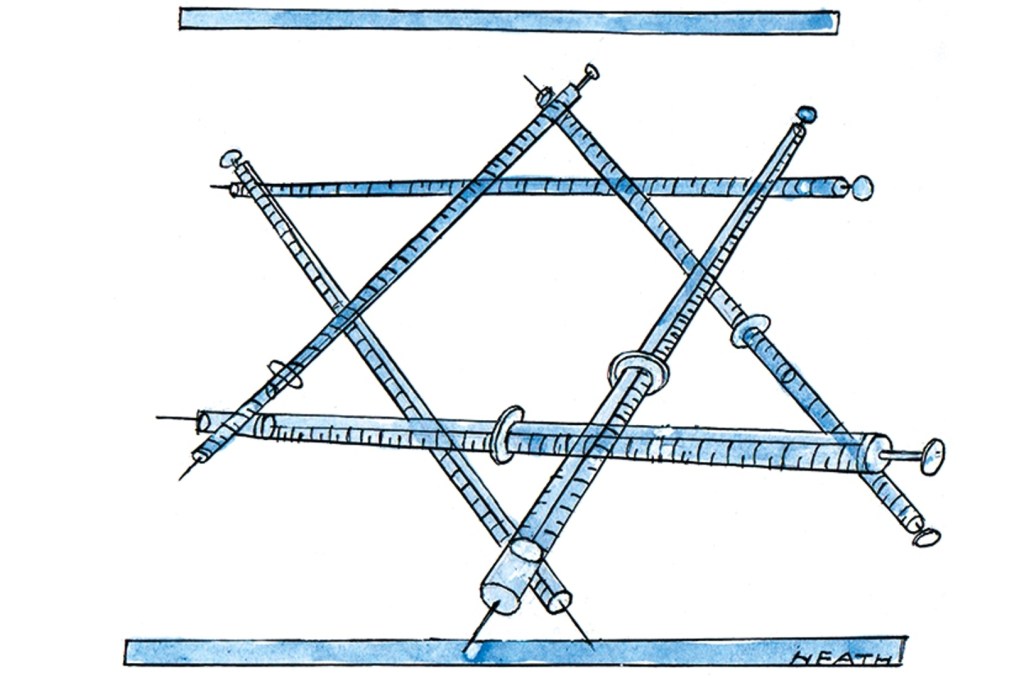

After three long lockdowns, and under a new government, Israelis are loath to accept that their newfound freedoms could be rescinded. The third vaccine ‘booster’ option was activated even though no other country or medical regulation agency (such as the FDA) had endorsed it. Israel has disregarded the warnings of the World Health Organization not to start giving booster doses while billions of people around the world are yet to have their first shot. Israeli public health officials say Israel is too small for its third jabs to make a dent in the global supply chain. ‘We’re not the reason there aren’t enough vaccines in Africa,’ says one public health official. ‘And besides, we’re doing the world a service by proving that third vaccines work.’

Naftali Bennett, the new prime minister, has repeatedly ruled out a fourth nationwide lockdown and is instead pushing for more vaccines, face masks in all public indoor spaces, and mass testing. Bennett is under political pressure as well. He is in a precarious position, leading a disparate coalition in which he is head of one of the smaller parties, and with his formidable predecessor, Benjamin Netanyahu — who presented the previous vaccine campaign as his personal triumph — constantly breathing down his neck. To make things worse, in the year before his improbable elevation to the top job, Bennett presented himself as an expert on the pandemic, even publishing a book, How to Defeat a Pandemic, and promising on coming to power that ‘we can beat coronavirus in five weeks’. He has been justifiably pilloried but is doubling down.

Israeli epidemiologists, public health officials and researchers have been in close contact with their British counterparts, from all levels of the National Health Service and the Health Department. Both countries vaccinated a similarly large proportion of the population early on. Both have well-digitized national public health systems capable of giving fast updates. Back in May, when it looked like the vaccine had COVID on the run, there was a lot of optimistic talk between British and Israeli officials on allowing free travel to those with vaccination certificates.

Israeli tour operators were gearing up for an influx of Brits on their summer holidays. But since then, the Delta variant has shown that it’s quite capable of infecting the double-vaxxed, albeit with far fewer hospitalizations. The more sensitive question is the waning of the vaccine’s protection over time. Israel, having started earlier, is feeling this effect first.

The British side hoped that the longer 12-week gap between the two doses (Israel kept to the Pfizer protocol of a three-week gap) prolonged the vaccine’s effect. Professor Ran Balicer, who heads the experts committee advising the Israeli Health Ministry on the pandemic, said that earlier on, the UK and Israel differed in their assessments of the waning effect of the vaccine after six months. ‘But our British colleagues are coming around to our assessment that it has gone down to about 42 percent effectiveness against infection. We’re still not clear on the effectiveness against illness, but it’s above 80 percent.’

Israeli experts already believe they have made the medical case for a third dose. But it is still far from certain that the government’s calculated gamble on avoiding lockdown will pay off. The only major restriction remaining is on the entry of non-Israelis to Israel and quarantines for Israelis returning from abroad. Over the next few weeks, the anything-but-lockdown policy will be tested when schools reopen and gatherings take place over the Jewish High Holidays.

The world is once again watching as Israel embarks on its policy of ‘containment’ — allowing the country to remain open despite the mounting number of infections (1 percent of the population currently has the virus). The result of this experiment may well affect how people in Britain and elsewhere get to celebrate this Christmas.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.