Since the beginning of the Ukraine war and the sanctions it triggered, energy prices have skyrocketed. President Joe Biden has called this year’s high energy prices “Putin’s price hike.” British prime minister Liz Truss told households that their high energy bills were a fair price to pay for solidarity with Ukraine. Margrethe Vestager, vice president of the European Commission, has encouraged Europeans to take short, cold showers to conserve energy. “When you turn off the water, say ‘Take that, Putin!’” she urged.

But are the high prices really Putin’s fault? He didn’t sanction himself, after all. It’s the West that chose to cut itself off from the Russian fossil fuels upon which it had come to rely. Moreover, the sanctions have failed — Russia’s corporate profits leapt 25 percent between the imposition of the sanctions and the end of August.

So what are the origins of the current energy crisis? When did it really begin?

Let’s play a game. Guess which year these headlines are from: “Curtailed ammonia production in Antwerp and Ludwigshafen.” “High natural gas prices lead to a shutdown of British fertilizer plants.” “Diesel Shortage Amid Soaring Prices: Truck Stops Resort To Rationing.” If you guessed 2022, you’d be wrong. Those are all from September 2021.

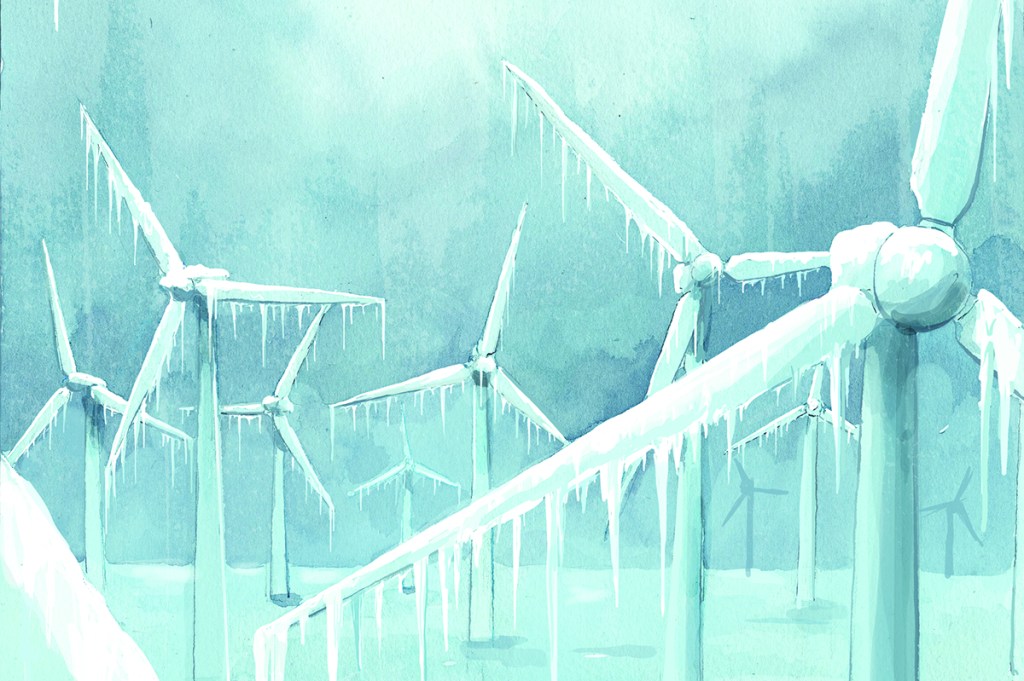

The truth is that the energy crisis began to take effect late last year. A combination of post-Covid demand rebound, a wind drought in Europe and depleted fossil fuel storage on the continent all collided to put serious pressure on the world’s industrial systems. Add the longstanding overinvestment in unreliable renewables, nuclear plant closures across the world in the wake of the Fukushima disaster and a global drop of more than 50 percent in oil and gas investment — from $700 billion to $300 billion — between 2014 and last year, and you have everything you need to kick off a global energy crunch. Russian tank treads running from the Donbas to Kyiv just made it all worse.

When politicians blame Putin, they’re deflecting from their own failures. It’s hard to blame them, especially if they’re European. Aluminum smelters in the EU have had to shutter operations, as have fertilizer plants, glass factories and various other manufacturers. Germany, the continent’s largest economy, is about to lose much of its manufacturing base to high energy prices. Industry and union leaders have been sounding the alarm for months, warning that Germany’s manufacturing sector could collapse without enough energy. And it’s not even clear Germany’s better-than-expected storage numbers are enough to get them through the winter without any flows from Russia.

Meanwhile, in the UK, the number of people behind on their utility bills mushroomed from 3 million to nearly 11 million between March and August. Eleven percent of the British population — nearly 6 million people — are already forgoing food to pay their energy bills. Would you want to be on the hook for any of this? It’s way easier to blame the evil Russian guy.

Don’t be fooled into thinking America is immune from the crisis. Sure, we have incredible domestic resources, but we’re moving in the European direction. Over the last few years, America has shut down nuclear plants before their time, including Palisades in Michigan and Indian Point in New York. The fossil-fuel industry isn’t interested in risking capital on expansion when the Democrats continue to saber-rattle about destroying it. Not since Truman has a president leased so few federal lands to the oil and gas sector. To make matters worse, most of the new capacity being added to the grid is intermittent and unreliable wind and solar.

The result of all this? America’s energy and electricity sectors look anemic, fragile and expensive. Over the summer, the National Energy Assistance Directors Association reported that about 20 million households in the United States — one out of six homes — are behind on their utility bills. Some parts of the country have seen electricity prices increase by 233 percent since last year. The North American Electricity Reliability Corporation has warned that a huge swath of the country is becoming increasingly vulnerable to blackouts. In August, a heatwave pushed the Texas grid to new demand limits for a week straight. The next month, the California grid operator had to beg consumers to consume less juice to avoid rolling blackouts. And don’t forget New England. Despite its proximity to the Marcellus Shale Formation in the mid-Atlantic states, the region lacks the pipeline infrastructure to import natural gas from it. The Jones Act, which bars foreign-owned vessels from delivering goods between US ports, has also hamstrung the region. New England’s liquefied natural gas, or LNG, import terminals cannot receive from the Gulf of Mexico’s LNG export terminals because while the United States produces the most LNG in the world, it does not make LNG tankers. So New Englanders will have to compete with Europe and Asia for pricey LNG to light and heat their homes this winter. That’ll be painful — natural gas is 53 percent of the New England grid’s resource mix.

But America doesn’t have to follow in Europe’s footsteps. Rather than doubling down on the “energy transition,” America should desensitize itself to the sobering truths of external events and commit to energy realism. After all, energy is indispensable to maintaining the economy. So, what would a more realistic energy policy look like?

First, we need more hydrocarbons. Fossil fuels are the master resource, like it or not. Everything that could possibly move us away from fossil fuels in the long run will need cheap fossil fuels for their construction in the near and medium term: from nuclear power plants to battery storage. We need to cut the red tape on permitting to fast-track more pipeline construction. We should also eliminate all carbon taxes, which increase our energy costs. And we must lease more federal land to the fossil-fuel industry. Eliminating the Renewable Fuel Standard, which has turned into an expensive financial boondoggle the burden of which companies pass onto consumers, wouldn’t hurt either.

Second, we need to liberate the atom. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has adopted safety standards so extreme that no design offered since its inception in the mid-Seventies has ever been completed. Its chosen radiation safety standard — “As Low As Reasonably Achievable” — relies on an incoherent measurement of radiation dosage and creates too much opportunity for regulatory activism. And the NRC’s approval process takes too long. The agency needs to be reworked so that its standards are fewer and clearer and its approval processes faster and cheaper.

Third, we need to harden our grid. Wind and solar, when built in large amounts, have a free ride on the reliable power plants that can be called on at will to ensure the grid keeps running. They also tend to stop producing power when they’re needed most. According to the Energy Information Administration, when California was on the brink of blackouts, solar and wind production plummeted. Natural gas stepped in to save the day, making up more than 50 percent of the resource mix after sundown. The fastest way to curb their growth and spare the grid more entropy would be to eliminate all production tax credits for wind and solar in perpetuity. That removes the incentive for overbuilding and spares electricity markets the subsidized negative prices that push reliable power plants off the grid.

Of course, embarking on this plan will mean taking on the environmental establishment, which views anything outside of renewable energy as an existential threat to mankind. But the choice should be obvious: one road leads toward liberty and abundance, another leads toward tyranny and austerity. We can live in a country where bureaucrats decide when we get to run our washers and dryers to spare our poorly managed infrastructure, or one where we can enjoy the freedom to pursue our own interests. We’re years down the road of the former, and the Inflation Reduction Act won’t help: it makes us even more dependent on unreliable electricity from wind and solar, increases taxes on oil and gas, gives the EPA nearly limitless power to curb fossil-fuel use and utterly fails to decriminalize nuclear. But it’s not too late to correct course.

During the energy crises of the 1970s, Amory Lovins, godfather of the renewable energy ideology, also invoked a choice between two energy paths: the “hard” path of large power plants or the “soft” one of wind, solar and biomass. He premised his vision on a misreading of Robert Frost’s poem, “The Road Not Taken.” In the poem, the paths present no real difference. Only in hindsight, as a post-hoc rationalization, does the illusion of choice appear. The speaker of the poem flatters himself by pretending he “took the one less traveled by.” Lovins was a bad reader and a poor thinker — he also consulted on Germany’s Energiewende, its “turnaround” to renewable low-carbon energy production. European leaders, and later American ones — not Putin — have chosen the soft path and volunteered for disaster. And that has made all the difference.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2022 World edition.