The triumph of Mark Carney in the Canadian election has turned what seemed like a series of local flukes into a global trend. The political mainstream has begun to despair of its own leaders, and now feels compelled to parachute in stately ex-mandarins of a slick, personalist style – figures who seem to stand above the factions. Call them “liberal Caesars.”

Carney is only the latest example. He joins the former banker and technocrat outside hire Emmanuel Macron, the ex-NATO chief Jens Stoltenberg installed as Norway’s finance minister, the statesman emeritus and top eurocrat Donald Tusk in Poland, the former spy-chief Dick Schoof of the Netherlands, the dour ex-chief prosecutor Keir Starmer – each are, in their own way, a sign of an essential loss of faith in civilian politics.

There is now a standard procedure for floating these kinds of figures. One or both of the mainstream parties collapses. Popular challengers begin to circle. Just when all seems lost, an unassuming ex-bureaucrat appears – often with unnerving speed – as a candidate of national unity. Policies, talking points, slogans, placards – all seem to have been prepped well in advance; and our candidate turns out to be not so unassuming as previously thought, now carrying themselves with a new swagger. There then comes a brief, seemingly mandatory burlesque about hidden sexual powers – from the Times of London alone: “Keir Starmer has turbocharged my arousal levels. I feel fruity” and “Mark Carney’s back! Let’s hear it for the (sexy) older man.”

These figures are chosen precisely because they are “above politics.” The act needs to be kept up, even in office. Keir Starmer, for example, has always been baffled by the internal lore of Britain’s Labour party and seems to think it’s somewhat below him to get up to speed; the current French President, meanwhile, has been keeping up an exasperated Mr. Smith Goes to Washington routine for about eight years. Puffed up beyond all reason, there’s a baroque self-seriousness that you don’t get with ordinary politicians. This is a strident, though not particularly ideological, style that aims to get a handle on an uncertain age through strength of résumé alone.

They have a tendency towards grandiosity that you don’t see with populists – who, in office, are on some level aware that they’re still in an insurgent position. It didn’t take long for Macron to start to compare himself to the thunder god Jupiter; and Keir Starmer has pictures of himself taken of a kind that, ten years ago, would have gotten any politician laughed out the room. People like Nigel Farage and Donald Trump make oppositional jibes at their foes; but with these figures it’s not entirely clear what they think the theoretical basis for dissent even is. Opponents are a “rot” that have reduced the nation to “rubble and ruin,” and are guilty of fomenting civil war. Mainstream politics becomes synonymous with themselves alone – Canada’s Liberals had all but collapsed before Carney’s arrival, and when Macron’s term runs out all bets are off.

Liberal Caesarism is now seen as the default fix to any problem. Time and again the first recourse has not been to new policies, but to new personalities – oddly grave ones. Of the major western countries not currently under populist governance, only Spain, Germany and the Antipodes are not making use of some neophyte ex-spy or financier.

Next to these figures, the current generation of populists can look startlingly normal. Giorgia Meloni, Viktor Orbán and Marine Le Pen all came to power as civilian politicians, doing the hard yards on the stump and in the debating chamber.

How to explain this new imperial style? The status quo has been running on emergency powers for over half a decade. Russia, Covid, supposed mass malfeasance in high office – anything that can bring about some general rallying to established institutions and a suspension of ordinary politics. It’s not a surprise that we now find it leaning more and more, not on the old parliamentary processes, but on transient charismatic authority.

Charismatic authority – but to what end? No one quite knows. There’s a cosmic pointlessness to these kinds of figures. The whole advantage of the personalist style lies in its reforming potential, its ability to cut some Gordian Knots. That was certainly the case with, say, FDR. But the new liberal Caesars are incapable of doing so. It’s just not who they are. These people – after all – came to power to defend a system under which courts and NGOs get the final say over how we live. Their role is grandiose but by the same token ceremonial: even if they don’t know it, their purpose is to win an election, look stately and distinguished, and let the unreformed system trundle on beneath them.

Every year or so there’s a hubbub in the British press about Macron’s latest big speech. At last, it’s said, the President is about to make good on the Jupiterian stagecraft by slashing the bureaucracy, or reforming the state pension, or uniting the Eurozone as a federal state. Nothing ever comes of it – much to Macron’s chagrin – because these figures are meant to be gilded bollards, not executives.

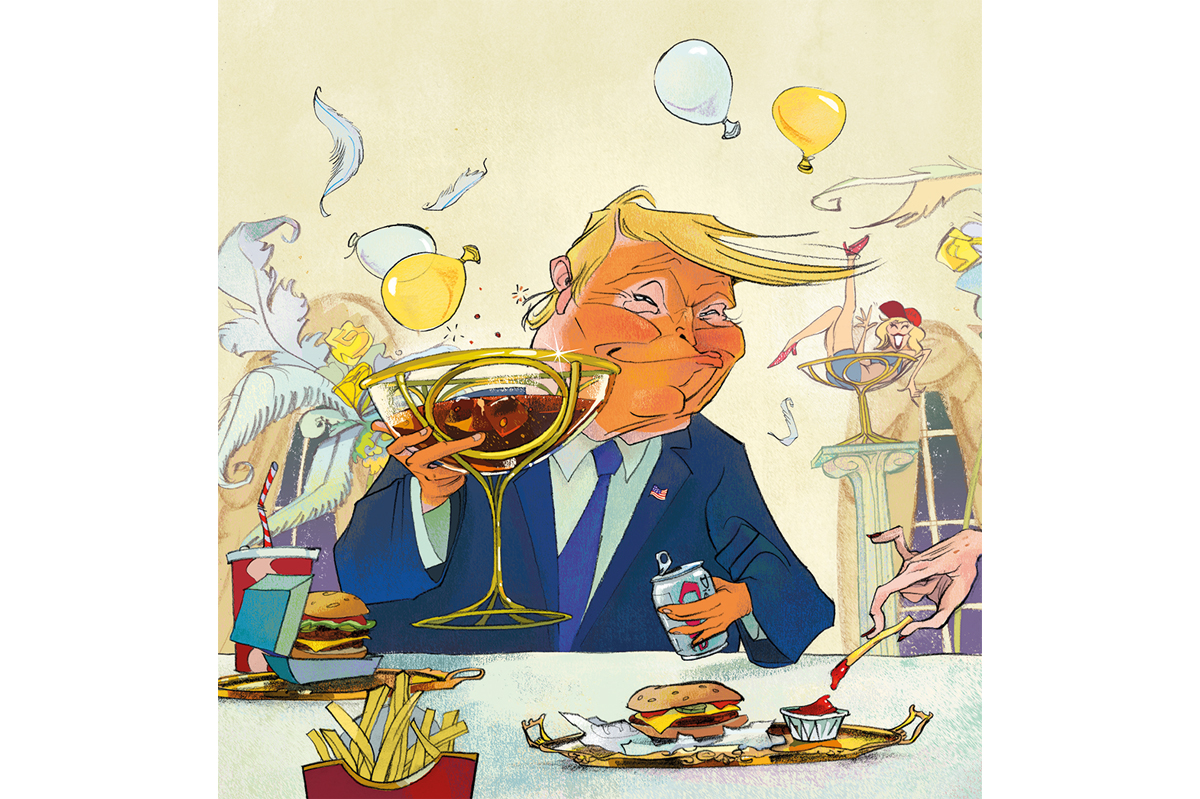

In this regard Starmer seems to know his role better than most. He has few if any settled beliefs, but he does very much believe in Prime Minister Keir Starmer. According to recent reports, he spent much of his first few weeks in Downing Street watching soccer on TV. Unlike his restless cousin Macron, Starmer knows what he’s there for: to be an imposing equestrian statue, and little else. What the Carney, Keir and Macron style seems to add up to is personalism and leader-worship with few actual policies, sustained largely by bluster and hot air. Now, doesn’t that criticism sound familiar?

Leave a Reply