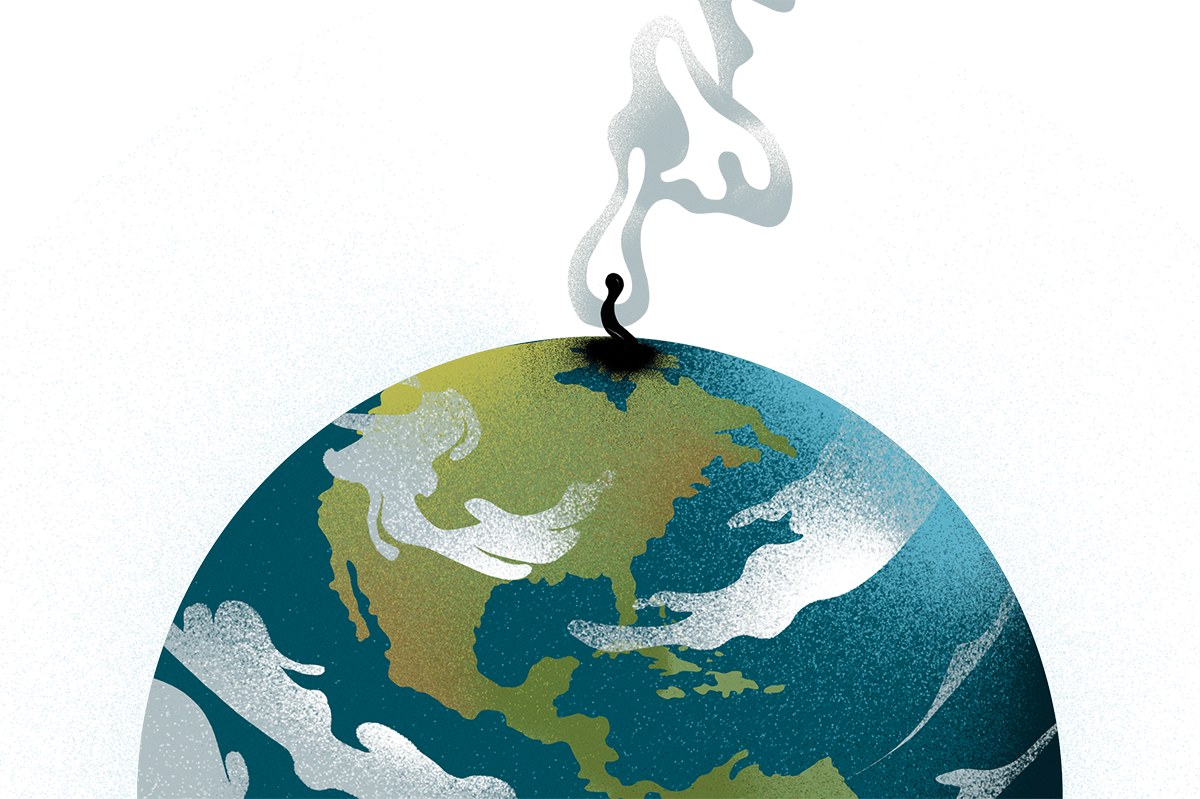

This has, so far, been a year of hard lessons. Spiraling inflation has given households an expensive economic refresher course. A land war in Europe has offered an unwelcome reminder of old geopolitical and military truths. But arguably the most important lesson of 2022 concerns the point at which these economic, military and geopolitical considerations converge: energy.

On this vital issue, the West has suffered from an epidemic of amnesia in recent years. Too often energy security has either been taken for granted by policymakers and voters, for whom the last energy crisis had become a distant memory, or actively disparaged by an environmental movement whose hardline hostility to fossil fuels has become received wisdom in polite circles. In other words: energy abundance was either something we didn’t need to worry about or something we actively disparaged. War in Ukraine has exposed both views as dangerous delusions.

The new energy crisis is being felt most acutely in Europe, where leaders have traveled further down the path to decarbonization than anywhere else. A rush to unreliable renewables, a turn against nuclear energy and an over-dependence on Russian gas is a recipe for energy disaster. As Emmet Penney explains, the cost of these mistakes has already been high. The budgets of European households have been stretched. And bad energy policy has also been environmentally self-defeating. To hedge against catastrophe, Germany has returned to bur ing coal. With winter approaching, the worst is yet to come. The apparent sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines in the Baltic Sea at the end of September was an inauspicious start to the colder months.

Americans have felt the consequences of rising energy prices too, of course, but things aren’t as bad on this side of the pond. One reason why is the shale revolution that began to transform the energy landscape over a decade ago, and has turned the United States into a net energy exporter. US oil and gas output surged by over 50 percent between 2010 and 2020. America’s ability to weather the current storm would be much reduced were it not for its abundant domestic supply of natural gas.

Yet no matter how loudly the energy-crisis alarm bells ring, many in the political and media classes remain committed to a hardline climate change agenda and refuse to heed the warning. In a recent grilling on Capitol Hill, Democratic congresswoman Rashida Tlaib asked bank executives if their firms had policies “against funding new oil and gas products.” JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon replied: “That would be the road to hell for America,” he said. The line stuck out for its bluntness. Dimon is obviously right — and yet such unambiguous statements of the importance of energy are strikingly rare among the Davos set to which Dimon belongs.

In some respects, Joe Biden has changed his tune. Over the summer, the president was forced to soften his stance on Saudi Arabia, fist-bumping Mohammed bin Salman in the hope that a bilateral with the Saudi prince might persuade OPEC to up production. (They did, but only marginally.) But beyond the occasional embarrassing flip-flop, the crisis has not led to a fundamental reassessment of energy policy in the White House. Biden wants to halve carbon-dioxide emissions by 2030 and achieve “net zero” by 2050. He scrapped the Keystone pipeline. He is in a court battle to uphold a ban he introduced on energy leasing on federal lands and waters. At the time of writing, his party’s lawmakers have so far failed to pass West Virginia senator Joe Manchin’s leasing reform legislation that would streamline the process for approving both green and fossil-fuel energy production. If the president and his party grasp the importance of energy abundance, it is only as a short-term political headache. As for the long-term, they offer nothing more than vague assurances about a green energy transformation.

Ahead of the midterms, energy is understandably seen first and foremost as a kitchen-table issue. Yet its importance goes beyond the cost of living. It is also an essential ingredient of a successful foreign policy. Great powers do not last long without a secure supply of energy. Biden promises a strong America on the world stage and claims an unswerving commitment to the international defense of democracy against autocracy. Without the dogged pursuit of abundant energy, victory in that clash will be difficult. But the significance of energy is deeper still.

Energy is nothing less than the lifeblood of civilization — hence why energy crises tend to coincide with broader crises of confidence. It is no coincidence that Jimmy Carter’s infamous malaise speech of 1979 — a wide-ranging attempt to address “a moral and a spiritual crisis” — was about an oil crisis and how America would respond. Carter’s address bombed because no one trusted him to deliver the energy independence he promised. But at least Carter was willing to prioritize that goal. Biden, by contrast, seems reluctant to even take that step.

From Europe’s policy mistakes to their geopolitical consequences, the energy lessons of 2022 are clear. The only question is whether Western leaders, especially Biden, are willing to learn.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2022 World edition.