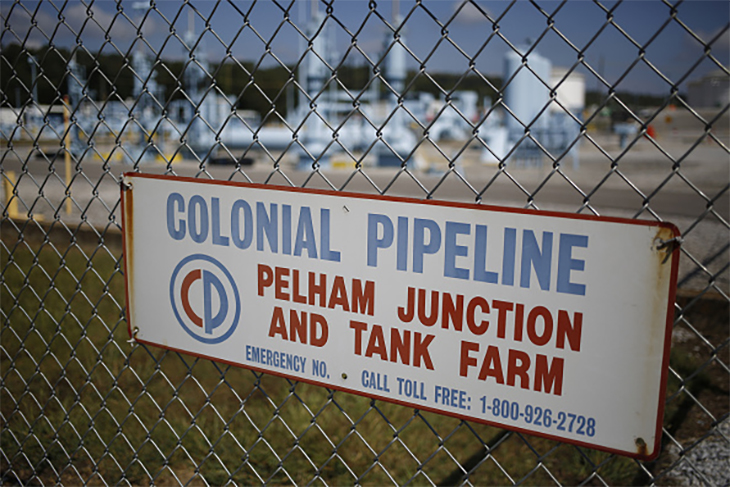

On a normal day, the Colonial Pipeline carries up to three million barrels of oil 5,500 miles from the Southern United States to New York, providing 45 percent of the East Coast’s fuel needs. On Friday, the oil stopped flowing. The pipeline was shut down after the operating company was hit by a cyberattack.

Two days later and the pipeline is still sitting idle, and companies are scrambling to try and secure supplies of oil, diesel, jet fuel and gasoline. The cyberattack raises international suspicions. Was it China? Russia? Those countries specialize in such actions. The NSA however has been briefing that the culprit was an unusual cybercrime outfit known as DarkSide.

DarkSide’s business is ransomware. They make tools that encrypt all the data on a target company’s network so the company can’t access their own files. Then they demand a ransom, usually payable in cryptocurrency, for the key to decrypt it and make it usable again.

DarkSide doesn’t just encrypt the data. It also steals it. Even if a company has backups, DarkSide threatens to publish confidential or sensitive information if the ransom isn’t paid.

But DarkSide isn’t a typical ransomware group, targeting small businesses with ransoms of a few hundred bucks. It has its eyes on bigger prizes.

DarkSide appeared about nine months ago and has something of a Robin Hood approach. They don’t target hospitals, schools or governments and they ignore small companies; they hit only big, rich corporations. DarkSide publishes press releases on their website (safely hidden on the dark web, of course). They run an ‘affiliate program’, offering independent hackers a 25 percent commission if they infect a company with the DarkSide ransomware, payable when the ransom’s delivered.

To promote the Robin Hood image further, DarkSide even donated part of a ransom to charity. The two non-profits, Children International and the Water Project, forfeited the money as proceeds of crime.

Is DarkSide a state actor? No Western government has made that claim, and both the choice of targets and love of publicity would be unusual for an Advanced Persistent Threat, a state-backed actor.

North Korea’s Lazarus Group has engaged in ransomware and theft in the past. And the DarkSide software has an interesting constraint: it’s programmed to avoid computers in Russia or other former Soviet countries. But this is more likely to point to Russian organized crime rather than a state-controlled intelligence agency.

Even giving DarkSide the benefit of the doubt, the Colonial Pipeline hack shows that there is no such thing as a righteous hacker.

Some banks might well deserve a good shakedown from a socially-minded hacker, but bank customers will suffer if they can’t use the money in their accounts to buy food. It’s all very well refusing to hit a hospital, but disrupting the fuel supply to millions of people could also have serious consequences. If the pipeline isn’t able to restart very soon, the East Coast could start to run out of gasoline, with untold consequences for families and small businesses.

These kinds of attacks will only become more frequent. Much of the US’s fractured infrastructure system has weak or nonexistent protection.

In February, a hacker accessed the controls of the Oldsmar water plant in Florida and turned up the sodium hydroxide, a caustic chemical that could have harmed people. The attack was noticed and quickly fixed, but it turned out that the hacker had entered, essentially, an unlocked back door into the system that had been open for months. Even worse, the computers were using the obsolete and insecure Windows 7.

Software updates, system upgrades, cybersecurity tools and good security practices are needed at every level of infrastructure, from local water plants to cross-country oil pipelines. Much of this infrastructure is in state, local or private hands. But protecting it is a matter of National Security.

In the meantime, as we all wait for the Colonial Pipeline to reopen, the story of Babuk and Washington DC’s Metropolitan Police might be instructive.

Babuk, which appeared in January, is a new ransomware gang with very similar methods to DarkSide but seemingly different politics. Babuk says it won’t hack non-profits — ‘except the foundations who help LGBT and BLM’.

Babuk stole data from the DC MPD in late April, supposedly including police informant files and materials from the active investigation into the January 6 Capitol riot.

Threatening MPD, Babuk said ‘f no response is received within 3 days, we will start to contact gangs in order to drain the informants, we will continue to attack the state sector of the usa, fbi csa.’

Concerns mounted that lives were in danger.

But the three days passed without incident. Perhaps the police paid the ransom. Sometimes you don’t have any choice.