There’s never been an older generation that didn’t complain about the younger one. Parents tut and fuss over errant youth. That’s the way of it. But in the end the kids come around. Swingers grow into Karens. The wild child pays his bills.

But kids these days… they do seem different. It’s not just that we, the older generations, are worried about them, but that they’re desperately worried about themselves. And according to Dr. Jean Twenge, a psychologist at the University of Chicago who studies generational changes, we’re right to worry. Almost 30 percent of American girls have clinical depression and it’s the same across the Anglosphere. The suicide rate for ten- to twenty-four-year-olds has tripled. “Let that sink in,” writes Twenge in her new book, Generations. “Imagine if nine airline flights filled with ten- to twenty-four-year-olds crashed every single year killing everyone on board. Airplanes would not be allowed to fly again until we figured out why.”

Twenge (fifty-one, Gen X) began looking at the differences between generations as a twenty-two-year-old doctoral student. She documented the rise in individualism that began with the baby boomers and continued with millennials. But it wasn’t until 2012 that she noticed the data really beginning to change. “There were abrupt shifts in teen behaviors and emotional states. The gentle slopes of the line graphs became steep mountains and sheer cliffs and many of the distinctive characteristics of the millennial generation began to disappear. In all my analyses of generational data — some reaching back to the 1930s — I had never seen anything like it.”

In 2017 she published a book about this distressed generation — “iGen,” as she called them — and identified the smartphone as the culprit. Now, six years later, iGen is more widely known as Gen Z, and Twenge’s theories are as good as proved. In her latest book she has crunched the data from polls and surveys involving 39 million people both in the US and in the UK. “The datasets don’t reveal their secrets easily,” she says. But when they do, it’s not pretty.

“There are some trends for young adults that are very strong and sudden that we have to start talking about,” Twenge says. “Two of those with Gen Z are the enormous rise in depression and self-harm.” Are you sure smartphones are to blame, I ask — isn’t the world just a bleaker place?

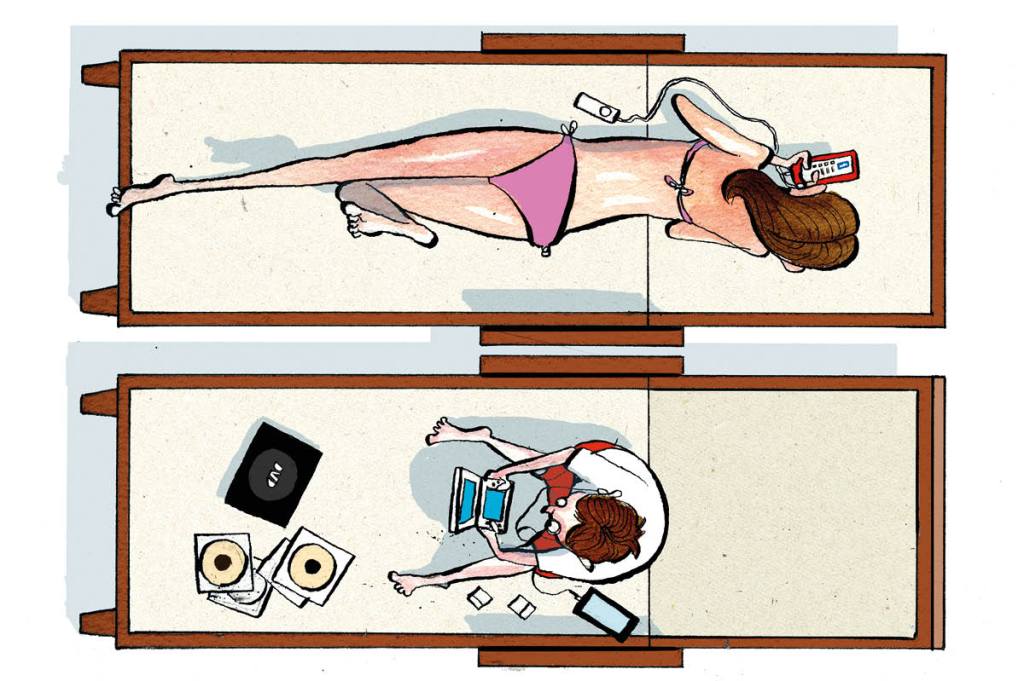

The more hours a day a teen spends on social media, the more likely it is that he or she is depressed. Some of the best data on that comes from a cohort study in the UK, says Twenge.

The generational psychologists of the past have assumed that it’s major events that create the character and attitudes of different generations. Twenge mentions Strauss and Howe, who think that generations cycle through four different types: idealist, reactive, civic and adaptive.

But Twenge believes it’s technology that forms us. “I think the long-term impact of these major events is fairly limited in terms of how it influences values and day-to-day life, but when you think about technology, especially with the downstream effects on individualism and life strategy, it has a much more wide-ranging impact,” she says. “It really is technology that makes living now different from what it was like to live 150 years ago or fifty years ago or even twenty years ago, rather than a big event.”

What is it about the tech that makes the young so sad, then? Wasn’t the internet supposed to bring us all together? I have a vertiginous flashback to 2007 or so when, full of excitement about the internet era, we had breakfast meetings at The Spectator to talk about the “digital future.” For a few years, if you thought up a snappy one-word title for your book, you could make a buck predicting the techno-utopia to come. I remember a man called Charlie telling me that if I wasn’t sharing constantly online, I would soon be irrelevant.

“I am sure there are collectivist ways to use the internet but a society that was already very individualistic is less likely to find those,” says Twenge. “Western society came into internet access with rising individualism already as a very strong trend. Individualism, like any cultural system, has its upsides and downsides — so the upside is more freedom, more opportunity for people regardless of their demographic make-up, and the downsides are disconnection and sometimes narcissism.”

And, according to Generations, an epidemic of loneliness. “One of the eye-popping facts is that teens are much lonelier now than they were fifteen years ago,” says Twenge. “And that’s true in thirty-six countries around the world when we were able to look at the PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) data.”

How can they be lonely, I ask? They’re always communicating. “There is just a big difference between interacting online and interacting face to face,” says Twenge. “Interacting face to face tends to be more cooperative and more emotionally close. It’s more honest but it’s also more agreeable. People have a very strong tendency online to say cruel things that they would never say to someone’s face.”

It’s somehow infuriating that there’s an epidemic of loneliness in the young. I want to shake Gen Z on behalf of what Twenge calls the Silents, the post-war generation. You have functioning legs and bladders, living friends, I want to tell them: leave loneliness to the old and housebound. But according to Twenge, amazingly, the Silents are the generation who need sympathy least: “They’re the least likely to be anxious and they are the happiest.”

Do her kids have phones? “My daughters are sixteen, thirteen and eleven and even my sixteen-year-old does not have social media,” Twenge says. Does that make her daughter lonely? Does she feel left out? “She has no trouble communicating with her friends.” Do her children see social media as unhealthy, like junk food? “I think that is a decent analogy. My sixteen-year-old and I have had many conversations about this, and she has come to see it as a waste of time and doesn’t seem to need it. She texts with her friends and calls them and that’s how they communicate.” So a phone, but no social media? “Correct.”

Gen Z needs our help — Twenge’s daughters aside. They’re so sad and so convinced the world’s appalling that they don’t even want kids themselves. “They are more likely to report that they don’t think they will have children, and that was particularly interesting,” says Twenge. “The percentage of eighteen-year-olds who say they were likely to have children was high and very stable from about 1976 to 2012 before it started to go down — so it was stable for that many decades and then started to change, which is really striking.”

They’ll say they can’t afford it, I suggest. But as Twenge’s book points out, millennials and zoomers are not materially worse off than previous generations were at the same age. The disadvantage is only in their minds. “Right — and for Gen Z right now we’ve got labor shortages.”

Some of the most astonishing data in Generations also show that Gen Z, in America at least, genuinely think that they live at the most misogynistic, racist time in history. But these things are demonstrably untrue, I say. Why are the kids resistant to facts? “My theory is that it’s related to the increase in depression,” says Twenge. “Depression isn’t just about emotion, it’s about thinking and cognition, it’s about how you see the world, and with more depression you are going to get more pessimism… Look, the negative view of the world of course has some truth to it. Every era has its challenges as well as its advantages. But I think if you take a step back and look at the time we’re living in, the advantages are often not talked about. Sure, there is still racism and sexism, but a lot less than there was fifty years ago.”

So the depression comes first and then the kids start looking for negative facts? “I think that’s the in and out of it. And I think it’s also that online discussions tend to emphasize the negative,” says Twenge. “There are several academic papers showing that negative news stories and negative posts on social media get more traction… it just seems to be the emotion that people respond to online. They are less likely to be interested in positive things and less likely to share them with others.”

Toward the end of our chat, I reveal my deepest worry: that there is now a widening, perhaps unbridgeable, divide between the generations, an idea that reading her book exacerbated. I’ve met three mothers recently who still have their Gen Z twentysomethings living at home, I told Twenge. All three said that in order to co-exist, they’ve had to agree simply not to talk about difficult subjects — ones they disagree on, such as gender or race, or even whether the world is getting better. These are left-leaning parents! The omertà terrifies me. If you can’t debate and discuss, you can’t reconcile. You can’t change and the generational divide can never close.

Twenge says: “There’s a big survey of university students in the US and over the past fifteen years students have become increasingly likely to say we need to prohibit racist or sexist speech and [agree that] colleges should be able to ban extreme speakers.” But who defines racist and sexist speech really? “Of course, right, and that’s why critics of these views have pointed out that such restrictions can be problematic.”

In her introduction to Generations, Twenge writes: “Generational differences also provide a glimpse into the future. Where will we be in ten years? Twenty?” I dread to think.

Are there any signs that younger kids are swinging around and becoming more tolerant, I ask hopefully? Twenge lets me down gently: “I think it’s in the hands of the older generations to turn this around. In the end we need social media companies not to be making billions from designing their algorithms to keep people coming back and on their apps as long as possible. And we need older generations to stand their ground when it comes to free speech.”

It’s a measure of our times, and the need for change, that this in itself is a brave thing for an academic to say.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2023 World edition.