‘To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle,’ George Orwell famously observed. He was talking not about everyday life but about politics, where it is ‘quite easy for the part to be greater than the whole or for two objects to be in the same place simultaneously’. For years before the 2020 election, nearly all American conservatives were in favor of standing up to Big Tech — but most were also against changing the laws and regulations enough to make such a stand effective. And yet the threat from Silicon Valley was literally in front of our noses, day and night: on our cell phones, our tablets and our laptops.

Writing in the London Spectator more than three years ago, I warned of a coming collision between Donald Trump and Silicon Valley. ‘Social media helped Donald Trump take the White House,’ I wrote. ‘Silicon Valley won’t let it happen again.’ The conclusion of my book The Square and the Tower was that the new online network platforms represented a new kind of power that posed a fundamental challenge to the traditional hierarchical power of the state.

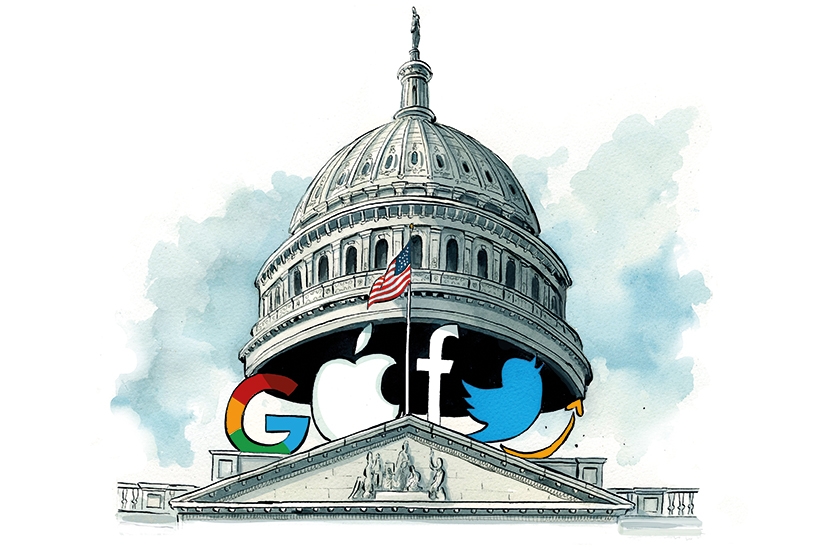

By the network platforms, I mean Facebook, Amazon, Twitter, Google and Apple, or FATGA for short — companies that have established a dominance over the public sphere not seen since the heyday of the pre Reformation Catholic Church. None had malign intent. As recently as 2008, not one of them could be found among the world’s largest companies by market capitalization. Today, they occupy first, third, fourth and fifth places in the market cap rankings, just above their Chinese counterparts, Tencent and Alibaba.

What happened was that the network platforms turned the originally decentralized worldwide web into an oligarchically organized and hierarchical public sphere from which they made money and to which they controlled access. That the original, superficially libertarian inclinations of these companies’ founders would rapidly crumble under political pressure from the left was also perfectly obvious.

Back in 2017, many Republicans still believed the notion that FATGA were champions of the free market that required only the lightest regulation. They know better now. After last year’s election Twitter attached health warnings to Trump’s tweets when he claimed that he had in fact beaten Joe Biden. Then, in the wake of the storming of the Capitol by a mob of Trump supporters, Twitter and Facebook began shutting down multiple accounts — including that of the president himself, now ‘permanently suspended’ from tweeting. When Trump loyalists declared their intention to move their conversations from Twitter to rival Parler — in effect, Twitter with minimal content moderation — Google and Apple deleted Parler from their app stores. Then Amazon kicked Parler off its ‘cloud’ service, effectively deleting it from the internet altogether. It was a stunning demonstration of power.

It is only a slight overstatement to say that, while the mob’s coup against Congress ignominiously failed, Big Tech’s coup against Trump triumphantly succeeded. It is not merely that Trump has been abruptly denied access to the channels he used throughout his presidency to communicate with voters. It is the fact that he is being excluded from a domain the courts have for some time recognized as a public forum.

Various lawsuits over the years have conferred on Big Tech an unusual status: public good, held in private hands. In 2018 the Southern District of New York ruled that the right to reply to Donald Trump’s tweets is protected ‘under the “public forum” doctrines set forth by the Supreme Court’. So it was wrong for the President to ‘block’ people — i.e., stop them reading his tweets — because they were critical of him. Censoring Twitter users ‘because of their expressed political views’ represents ‘viewpoint discrimination [that] violates the First Amendment’.

In Packingham v. North Carolina (2017), Justice Anthony Kennedy likened internet platforms to ‘the modern public square’, arguing that it was therefore unconstitutional to prevent sex offenders from accessing, and expressing opinions on, social network platforms. ‘While in the past there may have been difficulty in identifying the most important places (in a spatial sense) for the exchange of views,’ Justice Kennedy wrote, ‘today the answer is clear. It is cyberspace — the “vast democratic forums of the internet” in general… and social media in particular.’

In other words, as president of the United States, Trump could not block Twitter users from seeing his tweets, but Twitter is apparently within its rights to delete the president’s account altogether. Sex offenders have a right of access to online social networks; but the president does not.

This is not to condone Trump’s increasingly deranged attempts to overturn November’s election result. He not only egged on the mob that attacked the Capitol, he later said he ‘loved’ them despite what they had done. Nor is there any denying that a number of Trump’s most fervent supporters pose a threat of further violence. Considering the bombs and firearms some of them brought to Washington, the marvel is how few people lost their lives during the occupation of the Capitol.

Yet the correct response to that threat is not to delegate to Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, Twitter’s Jack Dorsey and their peers the power to remove from the public square anyone they deem to be sympathetic to insurrection or otherwise suspect. The correct response is for the FBI and the relevant police departments to pursue any would-be Trumpist terrorists, just as they have quite successfully pursued would-be Islamist terrorists over the past two decades.

The key to understanding what has happened lies in the 1996 Telecommunications Act and in particular Section 230, which was written to encourage nascent firms to protect users and prevent illegal activity without incurring massive content management costs. It states:

1. No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider

2. No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be held liable on account of… any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable

In essence, Section 230 gives websites immunity from liability for what their users post if it is in any way harmful, but also entitles websites to take down with equal impunity any content that they don’t like the look of. The surely unintended result of this legislation, drafted for a fledgling internet, is that some of the biggest companies in the world enjoy a protection reminiscent of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. Try to hold them responsible as publishers, and they will say they are platforms. Demand access to their platforms and they will insist that they are publishers.

This might have been a tolerable state of affairs if America’s network platforms had been subject to something like the old Fairness Doctrine, which required the big three terrestrial TV networks to give airtime to opposing views. But that was something the Republican party killed off in the 1980s, seeing the potential of allowing more slanted coverage on cable news. What goes around comes around. The network platforms long ago abandoned any pretense of being neutral. Even before Charlottesville, their senior executives and many of their employees had made it clear that they were appalled by Trump’s election victory (especially as both Facebook and Twitter had facilitated it). Increasingly, they interpreted the words ‘otherwise objectionable’ in Section 230 to mean ‘objectionable to liberals’.

You don’t need to be a Trump supporter to find all this alarming. Conservatives of many different stripes — and indeed some bemused liberals — have experienced the new censorship for themselves, especially as the COVID-19 pandemic has emboldened tech companies to police content more overtly.

You might think that FATGA have finally gone too far with their fatwa against a sitting president of the United States. You might think a red line really has been crossed when both Alexei Navalny and Angela Merkel express disquiet at Big Tech’s overreach. But no. To an extent that is remarkable, American liberals have mostly welcomed (and in some cases encouraged) this surge of censorship. It is tempting to complain that Democrats are hypocrites — that they would be screaming blue murder if the boot were on the other foot and it was Kamala Harris whose Twitter account had been cancelled. But if that were the case, how many Republicans would now be complaining? Not many.

No, the correct conclusion to be drawn is that the Republicans had their chance to address the problem of over-mighty Big Tech and completely flunked it. Only too late did they realize that Section 230 was Silicon Valley’s Achilles heel. Only too late did they begin drafting legislation to repeal or modify it. Only too late did Section 230 start to feature in Trump’s speeches. Even now, very few Republicans really understand that, by itself, repealing 230 would not have sufficed. Without some kind of First Amendment for the internet, repeal would probably just have restricted free speech further.

As Orwell observed, ‘we are all capable of believing things which we know to be untrue, and then, when we are finally proved wrong, impudently twisting the facts so as to show that we were right. Intellectually, it is possible to carry on this process for an indefinite time: the only check on it is that sooner or later a false belief bumps up against solid reality.’ That sums up quite a lot that has gone on inside the Republican party over the past four years. There it was, right in front of their noses: Trump would lead the party to defeat. And he would behave in the most discreditable way when beaten. Those things were predictable. But what was also foreseeable was that FATGA — the ‘new governors’, as a 2018 Harvard Law Review article called them — would be the true victors of the 2020 election.

Niall Ferguson is the Milbank Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2021 US edition.