I was seven months pregnant in March, 2020. I had miscarried before, and it had taken a little while to conceive, so even before the world became anxious about reports of a novel coronavirus, I was a nervous wreck. When the pandemic came in earnest, I was utterly overcome.

I had been working on a live news show. Every day in late February, and even at the very beginning of March, we were telling Americans to wash their hands, but that everything would be okay. Local politicians and medical experts came on the show to tell people it was all going to be fine. This was The Before.

One day, I came into the studio during a commercial. A doctor who had just finished reassuring the millions of American viewers that everything was fine turned to me after noticing my large and protruding stomach and said: “Go home. Go now. Don’t pass go, don’t collect $200, just go.”

The next day, I told my bosses I would be working remotely. Pre-pandemic, that concept simply didn’t exist in live television. Everyone thought I was hysterical. For the first few days, it was just me. Within two weeks, almost everyone was remote.

I spent the early weeks of the pandemic utterly crazed. I didn’t leave my New York apartment at all for five weeks, except for my OB checkups. When I did, I was the crazy lady that heckled people on the street. If you weren’t wearing your mask, or you were wearing it improperly, I probably yelled at like a deranged bag lady. I am sorry.

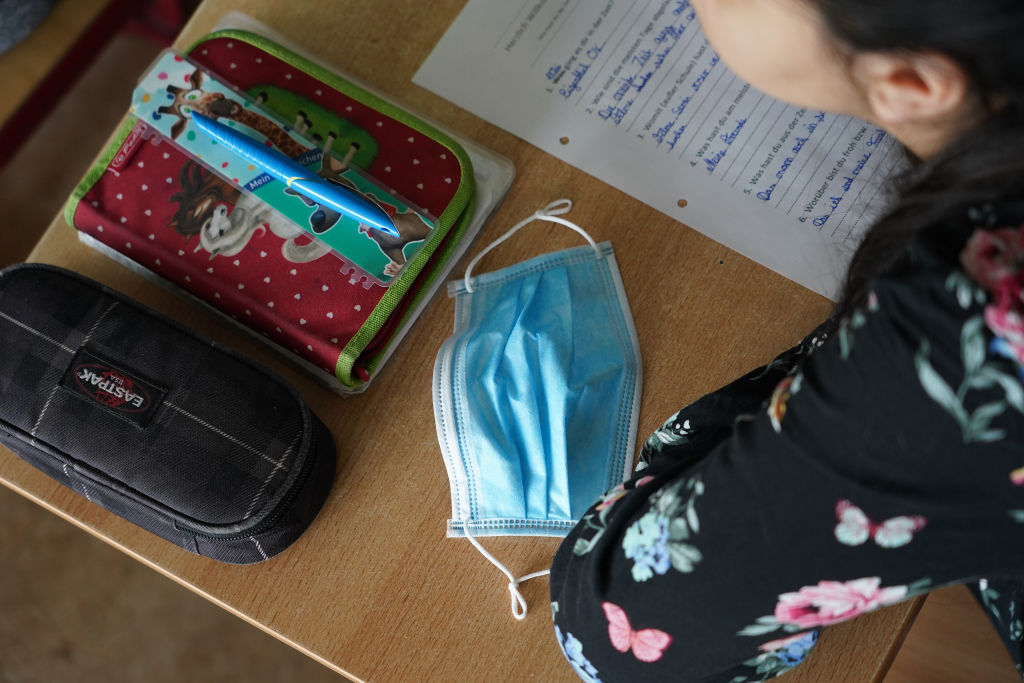

I went to the hospital to give birth utterly terrified that I would get Covid from one of the doctors or nurses. It was the first time in months we were around so many people. For twenty hours of unmedicated labor I kept my KN95 mask on, only taking it off around hour seventeen when they switched me to an oxygen mask.

Bringing my newborn home was no easier. The world was on fire and I was a postpartum mother terrified of not keeping her newborn safe. We saw no one in those early weeks except my parents, who had quarantined, tested, and still — as per my insistence — came wearing KN95 masks.

Over the next eighteen months, I was always two or three steps behind my friends. I continued to wipe down my groceries long after everyone had stopped. I got vaccinated as soon as it was available to me but didn’t adjust my behavior at all.

Then, one day, my daughter started talking. Suddenly, that same urgency I felt to protect her metamorphosed into something else. I began worrying that masks would hold back her development. These are incredibly formative years, and I didn’t want my nervousness to hurt her. And so, I began to change. I put her in every class available. I asked anyone around her to take off their masks so she could see their smiles and the way their mouths moved when they formed words.

Through normalizing her life, I began to normalize my own. Last November, I ate in a restaurant for the first time in almost two years. Last month, I was radicalized. My ninety-five-year-old grandmother showed up at the hospital feverish and out of it on a Saturday night. Thanks to the pandemic, the hospital’s policy is that adults cannot have people accompany them. For four hours, despite having arrived with an aide whose services she needs, she was alone, afraid, and confused in a crowded ER. I was outraged, but powerless to do anything.

The most frustrating part was that every single doctor and nurse we spoke to agreed on the futility of the rules and the unfairness of applying them to an elderly woman. But they weren’t in control: bureaucrats were. I finally understood the intensity with which people have been rebelling against Covid restrictions.

There is a technique sometimes employed in cognitive behavioral therapy called “flooding.” It is a straightforward method for curing a severe phobia: you take a person’s worst fear, and instead of exposing them slowly and gently to acclimate them to the situation, you engender a situation in which the most extreme version of the phobia is acted out. If you sought therapy for a fear of dogs, flooding might consist of locking you inside a room with thirteen pitbulls. It sounds traumatic and cruel, but scientists think it can be more effective than the traditional gradual approach.

The reason is simple enough: the human body simply cannot sustain the physical reactions that come with extreme fear forever. When the physical manifestations finally stop, your body and your mind learn that the thing which you feared is not so scary after all. Two years in, I am finally flooded from Covid. I can no longer sustain being a crazy Covid lady. And if, in my own myopic concern for myself and my family, I didn’t realize you were flooded too, I yelled at you for living your life and not wearing a mask, I’m sorry.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2022 World edition.