The new comedy Splitsville amusingly diagnoses several urgent social ills. The film mocks those who treat marriage not as an expression of solemn vows but as a ticket to unfettered happiness to be discarded at the first sign of discontent; it also excoriates those who view the institution as so meaningless – just a piece of paper – as to persist in the midst of openly acknowledged affairs, romances and one-night stands.

In its own coarse, fumbling way, Splitsville has an instinctive sense of how human beings long for monogamy and order even while they court freedom and licentiousness.

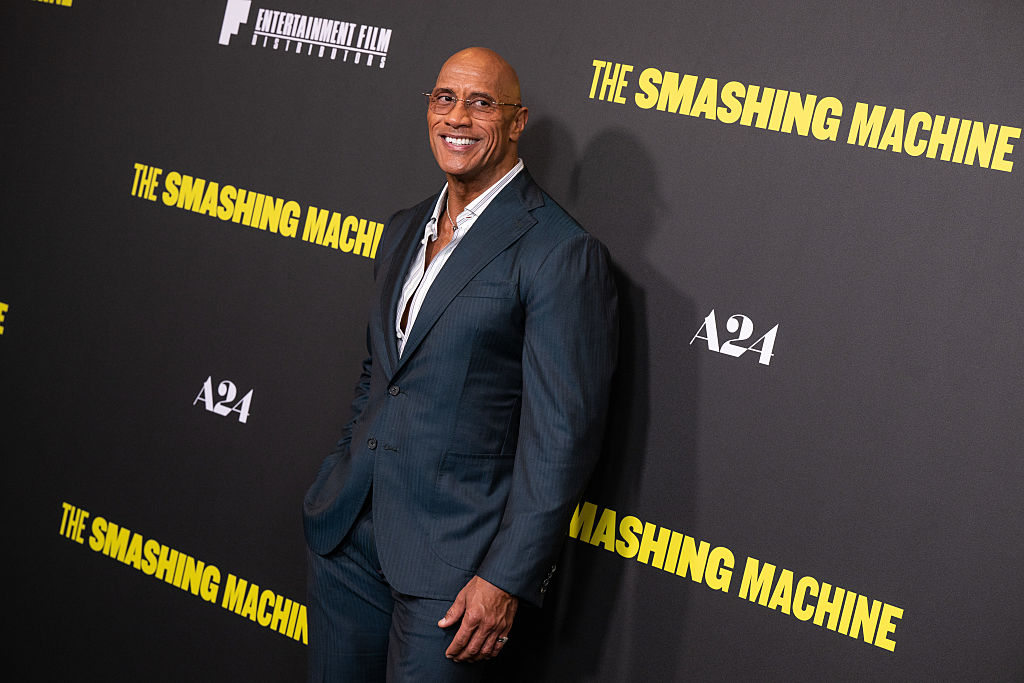

Splitsville stars Kyle Marvin and Adria Arjona as Carey and Ashley, a young couple who, 14 months after getting hitched, find themselves with different notions about the success of their union. Carey, a go-along-to-get-along pushover, yearns for fatherhood, while Ashley, a life coach bent on her own ever-changing self-actualization, finds herself restive. After Ashley hastily announces her intention to separate while on a road trip, Carey – whose androgynous-sounding name suggests something of his lack of moxie – abandons their car and, in comic fashion, treks through a series of geographically questionable dirt roads, byways, marshes and lakes toward his destination, the paradisal home of his seemingly well-off best friends, marrieds Paul (played by director and co-writer Michael Angelo Covino) and Julie (Dakota Johnson).

Paul and Julie are presented as the picture of wedded contentment, but when pressed as to the secret of their success, they insist it is because they maintain an “open marriage” – in other words, theirs is a judgment-free zone in which each is free to gallivant with others. “Do you know why people break up? Guilt,” Julie asks, setting up one of the most pitiful philosophies for life imaginable: “But if you make the bad thing OK, then there’s no guilt.” In his vulnerable position, and as a full-fledged member of the fallen human race, Carey quickly takes advantage of this laissez-faire environment of permissiveness by initiating a liaison with Julie. After Carey glibly confesses this rendezvous to Paul, however, the two men find themselves mugged by reality, so to speak: there is no chance a husband would not be jealous of an unfaithful spouse and angry toward her lover. The two men then engage in one of the lengthiest and most robust movie fights since the one between Roddy Piper and Keith David in John Carpenter’s They Live (1988). A table is smashed; a child’s fish tank is drained of its contents. The scene is not only a comic tour de force but also an expression of the total unworkability of an “open marriage.”

Carey is soon to find this out for himself when, exiled from his friends’ home, he returns to the residence he once shared with Ashley, who is living with a man named Jackson (Charlie Gillespie). Unlike Paul, Carey keeps a lid on his temper, but his façade of nonchalance is just that: a façade. At one point, Carey badly paraphrases a line from Vanilla Sky – something Cameron Diaz said about when you sleep with someone, your body makes a commitment. Although the moment is played for laughs (he quotes the line without attribution at first), the movie underscores its wisdom. Carey feigns friendliness with Ashley’s lovers, but only so as to annoy his spouse. For his part, Paul is revealed to have been less than fully committed to his own “open marriage” program: Late in the picture, he reveals that he proposed such an arrangement because he was not confident that his wife would stay with him and therefore wanted to bake infidelity into the marital cake. It is hard to imagine a more confused coterie of characters.

Splitsville presents a grim, almost apocalyptic vision of modern people trying and failing to free themselves from society’s strictures. This inclination for rebellion has even spread to Paul and Julie’s son, Russ (Simon Webster), who, when attempting to explain away his participation in a fight at school, says, “The school system is broken” – as though a sociological cliché would excuse his bad behavior.

The film’s characters change partners with great ease, yet it will be obvious to any student of screwball that Splitsville is hurtling toward a familiar finish. Ashley sees the error of her ways and reunites with Paul, while Julie reaches some sort of détente with Paul that is short of a full-scale reunion – she seems to permit him to hang around their house in perpetual pursuit of her.

Like No Hard Feelings, the Jennifer Lawrence vehicle from 2023, Splitsville is part of an earnest effort to revive R-rated, non-woke comedies. Its humor is crude; its pieties are few. This is relatively refreshing, but by my lights, it elicited far fewer laughs than The Phoenician Scheme or the Naked Gun reboot, the funniest films of the summer. Instead of laughing, I found myself grimacing in a shock of recognition at our depraved manners and mores. Yet Covino deserves credit for not reveling in but exposing his characters’ faults and for acknowledging that what ails these couples can only be resolved by the restoration of their vows.

Leave a Reply