This article is in

The Spectator’s inaugural US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.

You have no phone service, no television, no GPS for the car and no road atlas because you threw it out in 2009. Planes aren’t flying, and that spinning sound you can’t hear is the sound of space hardware floating out of our control. So dependent have we become on satellites for everything from communications to traffic control that a day without them would mean catastrophe.

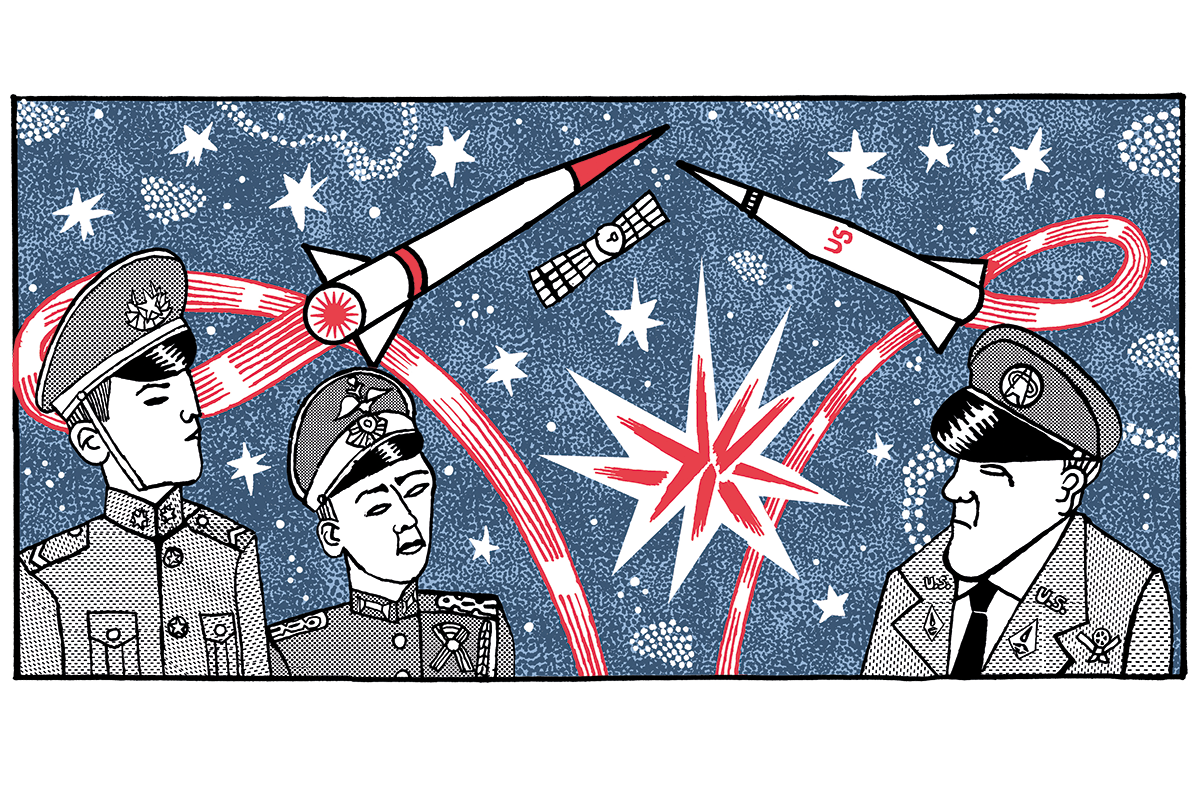

In the new space race, victory won’t mean landing on the moon or sending a rocket to Mars, but developing a new arsenal to wage and win war in space. On this new frontier of warfare, the critical advantage will belong to the combatant who renders the enemy deaf, dumb and blind in the first stages of a conflict.

War in space has been a beloved and popular idea for novelists and filmmakers, though the plot lines changed slowly. Secretly, however, it’s been a different story for the big three space powers, the US, Russia and China. Foreign hackers have broken some of the codes that are integral to controlling the movement and effectiveness of satellites, a scenario resembling War Games (1983), in which teenage gamers play their way to the edge of thermonuclear destruction.

In 2018, President Trump recognized the reality of ‘Star Wars’ — the Reagan policy, not the movie — and announced the formation of Space Force, the first new branch of the military in more than 70 years. In August, Trump authorized the launch of the US Space Command into what he called ’the next war fighting domain’.

Space Force will protect American space assets and, in the first stages of a new war, destroy enemy satellites. The US Air Force has already started teaching space strategy and tactics to a new generation of officers. Space Force will become a reality next year. By then, the US hopes to have developed weapons and defenses for war in space.

These moves reflect growing concern in the Pentagon and the intelligence community that the US is vulnerable to attacks in space from a wide range of bad actors. All US military communications are dependent on satellites, as are 90 percent of communications intercepts and other forms of intelligence gathering. If American satellites were knocked out, it would be almost impossible for the Pentagon to wage war.

The militarization of space is governed, in theory, by the Outer Space Treaty, created in 1967 by the United States, Russia and Britain, and signed subsequently by another 106 countries. Fifty years on, the treaty is hopelessly outdated. It governs the peaceful exploration of space and bans the placing of nuclear weapons there. But it didn’t ban the placement of conventional weapons in orbit, and it could not foresee all of the technological changes that, by altering the balance of power in space, threaten to alter the geopolitical balance on earth.

One major challenge in planning for war in space is that Anti-Satellite (ASAT) weapons come in many different forms. One approach, obviously, would be to launch a missile from the ground. Another would be to blind or destroy a satellite’s sensors by using a space-based laser. A third might be to create a collision in space between two satellites.

A second challenge is that targets are hard to identify. Much of what happens in space is secretive. There are hundreds of objects up there. Some may be perfectly innocent, some might have dual-use capabilities, and some might be killer weapons. Since 2013, Russia has launched three satellites that US intelligence believes may carry ASAT weapons.

The Russians claim they are using these satellites to inspect and perhaps repair their existing satellites. Yet these three satellites have also approached other countries’ satellites. They’ve been turned on and off, and are currently dormant. To a professional observer, these actions are all suggestive of a space-based weapons system.

The militarization of space has been surprisingly slow. During the Cold War, the US and Russia had extensive ASAT programs. But Russia shut down its program in 1990 after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and America’s efforts went largely dormant too. Today, Russia’s revived ASAT program is working flat-out to secure space dominance, and the US and China are equally determined. Sources tell me that the US intelligence community is certain that Russia, China and India already have ASAT capabilities, and that North Korea and Iran have programs in development.

In what may be ranging shots for a future satellite war, both China and Russia are thought to have experimented with hacking and jamming American satellite signals. This may prove a more attractive tactic than simply destroying American satellites; cyber attacks and jamming signals are difficult to locate, let alone to pin on a particular government. North Korea has bought jamming systems from Russia.

Insurgents in Iraq have also used Russian jammers to intercept American signals, while Afghans prefer commercially available models.

The most promising weapons in this new form of warfare are high-powered lasers, accurately fired from ground stations at targets in space. China has fired lasers at American reconnaissance satellites flying over its territory, and the US believes that by next year it may have ground-based lasers capable of destroying a satellite’s optical sensors. For its part, the US Air Force has already successfully fired a laser from an aircraft against a satellite in low Earth orbit.

The United Nations and various scientific groups are trying to update and expand the Outer Space Treaty. Their work has largely gone nowhere. Space war is already an emerging reality, and no treaty can prevent major powers from trying to ‘shape the battlefield’ in advance.

Down here on the ground, it’s a good idea to buy a wind-up radio and keep that landline phone connection. And get a road atlas, just in case.

This article is in The Spectator’s inaugural US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.