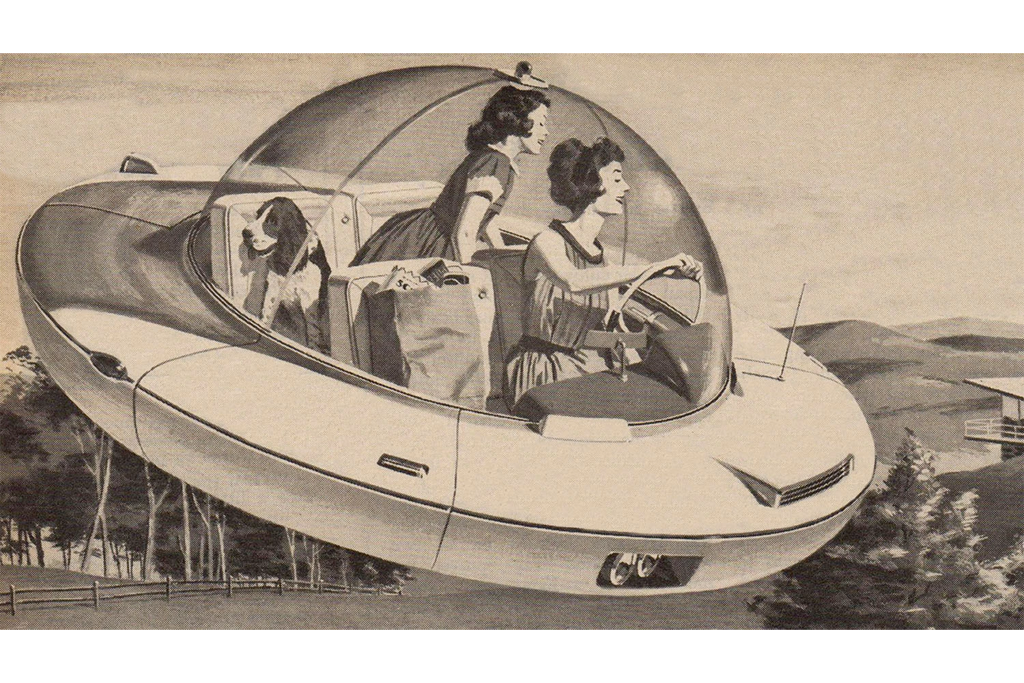

Sometime in 1953, Dorothy Martin was contacted by aliens. They had bad news and they had good news. The bad: Earth was about to be swallowed up by floodwaters. The good: as the leader of a chosen few, Martin would be saved by flying saucers. Mankind had brought this calamity on itself by following Lucifer’s agents – scientists – and abandoning Christ. Over the next year or so, Martin assembled a little flock of disciples who believed their salvation, and the world’s end, would come on December 21, 1954.

A team of psychologists caught wind of Martin’s prediction. Leon Festinger, Henry Riecken and Stanley Schachter saw in Martin an opportunity to test a hypothesis: when people with strong convictions are faced with incontrovertible evidence that their beliefs are wrong, those believers will increase their proselytizing efforts rather than admit they’re wrong. Festinger and his little flock of scientists covertly infiltrated the religion and had their hypothesis confirmed when neither the flood nor the saucers materialized: faced with dissonance between faith and reality, Martin and her closest followers doubled down on the former. Festinger and his co-authors wrote up the nutty experience in When Prophecy Fails (1956), which became the basis of the theory of cognitive dissonance and scripture in the field of psychology.

One nitpick: they lied. As the political scientist Thomas Kelly recently discovered, Festinger’s researchers distorted key findings, misrepresented their actions and betrayed basic scientific standards.

Kelly first read When Prophecy Fails a couple of years ago. The whole thing seemed too neat. He noticed strange inconsistencies. Festinger, for example, claimed that Martin had only around eight true-believing disciples – and even among those eight there were wafflers. A year later, in his seminal A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance he claimed there were “25 to 30 persons” who “believed completely in the validity” of Martin’s messages. So Kelly went looking for the psychologists’ notes. The firsthand accounts of the researchers’ time among Martin’s followers are held at the University of Michigan’s Bentley Historical Library. Festinger’s family donated the box but ordered that it be sealed for 70 years. That decree expired this year. And Kelly has cracked the box open.

In poring over hundreds of pages of notes, Kelly noticed the researchers had left key observations out of the book. For example, they knew that Martin had engaged in serious evangelizing for months – writing to magazines, teaching neighbors and children – prior to the failure of her prophecies. But they leave nearly all of this out of the book to make their hypothesis appear stronger. Toward the end, the authors write that the core of the group emerged from their reality check with “faith, firm, unshaken, and lasting.” There is simply no evidence of this. In fact, Martin spoke to the UFO magazine Saucerian in 1955 – a year before When Prophecy Fails was published – recanting her belief in the UFO rescues. Kelly calls this fact check “trivial” – yet no one had performed it, apparently. “Maybe snobbery,” he says, explains why no other academic has bothered to look this stuff up.

But these slip-ups look minor compared to the other offenses Kelly uncovered. Any high schooler can tell you that a scientist isn’t supposed to influence his subject’s thinking. The authors of When Prophecy Fails’s acknowledge that their presence in the group may have had some influence, but they insist that it was passive and minimal – they were little more than flies on the wall.

It would be a problem then if, say, one of the lead researchers somehow became a de facto leader within the religion. But, whoopsie, that’s exactly what co-author Henry Riecken did. As “the favorite son” of those higher beings, Riecken earned the special title Brother Henry and was called upon to aid the faithful in moments of spiritual crisis. After one of Martin’s key prophecies failed, Brother Henry issued cryptic words to the group that reinvigorated their faith and, as he put it in his notes, “precipitated” their renewed evangelism.

But that was not even the researchers’ most disturbing act. Just before the world was set to end, a social worker appeared at the household of the Laugheads, some of Martin’s most dedicated followers. Charles Laughead’s sister had called the worker to check on her nieces and nephews, whom she feared were being neglected by the UFO-obsessed parents. A research assistant answered the door and saw the threat this intruder posed to the study’s continuation; she rebuffed the worker and then urged her higher-ups to delay the case. In a particularly twisted note, the researcher claims she’d also done this because she’d grown affectionate toward the Laugheads’ youngest child and wanted to “protect” her.

Look through these files – which Kelly has put online as open-source – and one thing you’ll notice is the contempt in which the researchers hold their subjects. Martin’s followers are called “idiots” and “pigs.” These are not the words of neutral observers.

The irony in all this would be funny, if it weren’t so sad. For decades, When Prophecy Fails has been used to bludgeon religion. In New Testament studies, for example, many academics take it for granted that Christ’s resurrection did not occur, and they’ve used the book’s analysis to explain why evangelism took off even after this anticlimax. These scholars have showered condescension on those they believe hold unexamined – which is to say, non-atheistic – convictions. Never mind that these same intellectuals have fallen victim to the false prophets Festinger, Riecken and Schachter for the past 70 years, or that When Prophecy Fails is just one of a spate of major social-science studies to be debunked in recent years. The prophets of this reigning pseudo-religion – psychology – seem to be failing. Will their followers see the light? Or double down on their delusions?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply