Something extraordinary has happened. It wasn’t just the docking of a SpaceX capsule at the International Space Station, some 250 miles above the Earth, on a mission to rescue stranded astronauts. It was the sight of Americans and Russians embracing. As the new arrivals — Nick Hague and Aleksandr Gorbunov — appeared through the hatch, it was hugs all round. There are now four Russians and seven Americans manning the ISS.

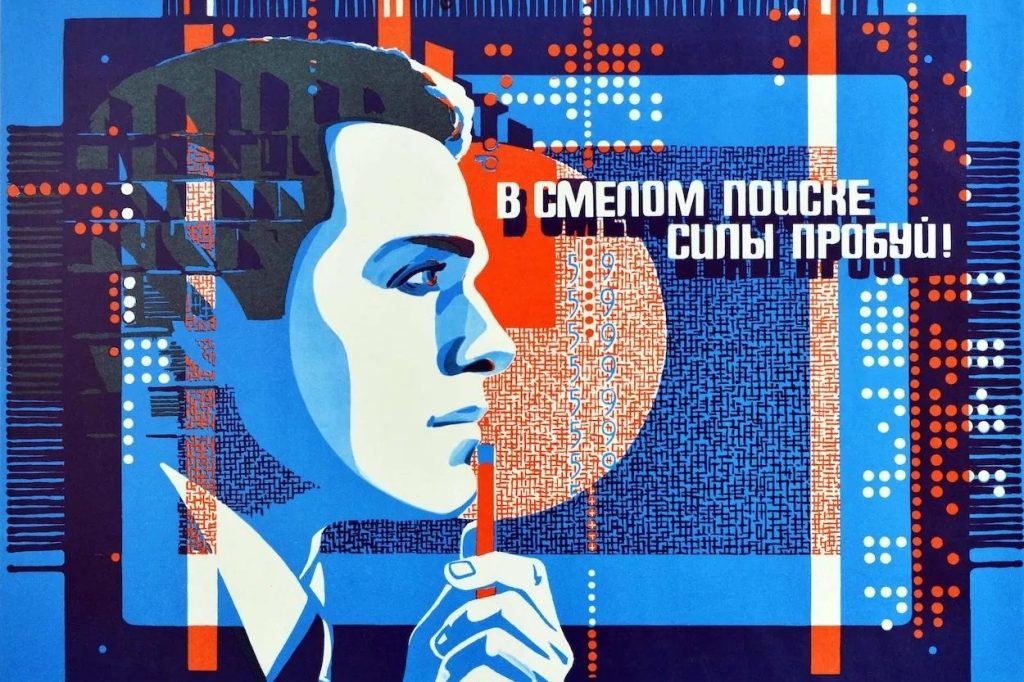

Since the outbreak of the war, collaborations with Russian scientists — measured by the co-authors named on papers — have dwindled across the West

Then consider that this happened just a few days after the International Chess Federation voted to extend its ban on Russian grandmasters competing internationally. That’s got to hurt. Chess means more to Russia than it does to any other nation. Ever since the time of Lenin, who was crazy about the game, the country’s skill at chess has been a source of pride. From 1927 to 1990, all but two world championships were won by Soviet players.

Which leaves us with a puzzling question: why should we work with Russians in space but not compete with them over the chessboard? As the director of a research center with many Russian researchers, I’ve thought about this. The cynical argument is that, in both cases, it is self-interest. With Russians out of the running, we’re more likely to win a game of chess. As for the ISS, which costs $3 billion a year, there’s too much money involved to close it down.

There is another argument, of course, which is that it depends on the value of the activity in question. Like other sports, chess can inspire as an analogue of the human pursuit of excellence. Science, though, is also the pursuit of knowledge, which is more than just an analogue. It has an intrinsic value that transcends politics.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the London Institute for Mathematical Sciences, where I work, chose not to close down collaborations with Russian scientists. On the contrary, we moved fast to create new positions for researchers affected by the war. As well as Ukrainians, these include Russians who no longer wish to work in their native land.

This is simultaneously in our interests, because we get to work with the smartest people, and because it is the right thing to do. Many Russian scientists find themselves in occupational limbo, unwilling to return home but denied visas to work elsewhere. Yet Britain’s Global Talent visa smooths the way for the best scientists to join workplaces like mine from other countries, including Russia.

Since the outbreak of the war, collaborations with Russian scientists — measured by the co-authors named on papers — have dwindled across the West. The German government took the draconian step of banning joint papers altogether. The particle physics lab at Cern has just announced it will expel hundreds of Russian scientists by December. Over the last two years, China has overtaken America and Germany as Russia’s biggest scientific collaborator.

At the London Institute, we’re proud to fly in the face of this trend. In fact, today we’re announcing a new program of postdocs for Russians. The Khodorkovsky Postdocs, which are funded by the Khodorkovsky Foundation, will allow young Russian physicists and mathematicians to join us for two years in our rooms in the Royal Institution in Mayfair.

We do this with the support of Sir Richard Catlow, chairman of the Royal Institution’s board, and a former foreign secretary of the Royal Society. As he likes to point out, the Royal Society had a foreign secretary before the British government did. The implication is that internationalism in science takes precedence over internationalism in politics.

Chess, a game of abstract patterns, has always been an international pursuit. It was invented in India around 600 AD. The phrase “checkmate” comes from “shah mat,” which is Persian for “the king is helpless.” According to one story, the game was first brought to Britain by the Danish king Canute, after he picked it up during a pilgrimage to Rome.

Our work at the London Institute is done in mathematics, which is the universal language of patterns. In the footsteps of physicists from Faraday to Landau, we aim to uncover the laws of the universe so we can better understand our place within it. Like chess, that’s an international game, and we’ll play it with anyone willing to sit down at the board.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.