The Special Air Service (SAS) is worried. Members of Britain’s most elite military unit have come face to face with the IRA, the Taliban and ISIS. But the enemy that really concerns them doesn’t carry a gun or wear a suicide belt. It’s the phalanx of lawyers they think are coming for them, armed with a deadly weapon: the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Many SAS soldiers now believe that if they pull the trigger during an operation and kill a terrorist, they’ll spend decades being hounded through the courts. They don’t trust the chain of command to look after them. They accuse politicians of a “betrayal.” That’s hurting morale and may eventually hit recruitment. Britain may all end up being less safe because of it.

This picture of discontent inside the SAS comes from George Simm, a former Regimental Sergeant Major, who wore the winged dagger for twenty-three years. I could not speak to serving soldiers or officers: the SAS observes a strict omertà. Simm was one of those who drew up the current contract forbidding “disclosure” that everyone joining has to sign. He commands immense respect within Britain’s Special Forces and was once described as an SAS “centurion.” He was at the regiment’s base near Hereford recently for a funeral and heard widespread complaints. He says: “The mood in the camp is dark. They know that service with the regiment is maybe ten or fifteen years — and the rest of your life is being chased by lawyers.”

Simm tells me about someone he still calls “one of my young lads,” who served thirty-four years in the SAS, but who has been mired in a legal process for more than twenty. “Soldier M” was part of an SAS squad that killed four members of the IRA’s East Tyrone “brigade” in 1992. The IRA men had just attacked Coalisland police station with a heavy machine gun mounted on the back of a truck. They drove to the car park of a nearby church to change vehicles and dismantle the machine gun, but the SAS was waiting there for them. Soldier M and his comrades are being asked, once again, to account for their actions on that dark February night thirty-two years ago. This time, it’s an inquest, heard before a High Court judge and convened under the ECHR’s Article 2, which protects “everyone’s right to life.”

To Irish Republicans, the four IRA men are martyrs, set up to be assassinated by the SAS, victims of a British government “shoot to kill” policy in Northern Ireland. Simm says the SAS had to catch members of the IRA “armed, hooded and intent on killing,” otherwise they would just have to let them go. He dismisses the IRA as good at murder but not at fighting: “gangsters” or “keen amateurs.”

That fits with reports of the attack in Coalisland. The IRA “active service unit” stopped during their getaway to fire into the air, wave an Irish tricolor from the back of the truck and sing “Up the Ra.” But the weapon on the IRA truck was a Russian “Dushka,” an anti-aircraft gun firing .50 calibre bullets that can take someone’s head off two miles away. The four IRA men also had Kalashnikovs. They were “considered a threat” when they were killed.

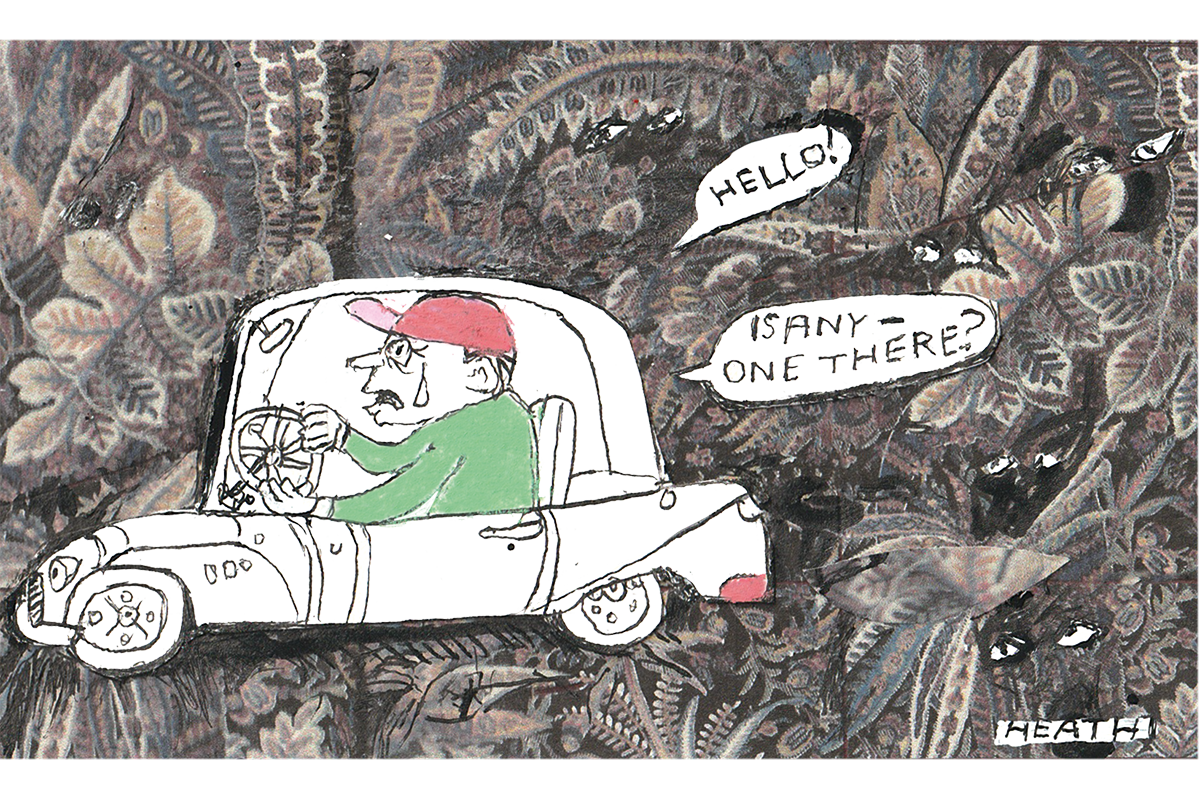

Many soldiers believe that if they kill a terrorist, they’ll spend decades being hounded through the courts

Soldier M tells me he has had to give a statement about that night “four or five times,” starting with the original police inquiry in 1992. Back then, it was “just another operation” to him, but he has been haunted by it because of what has happened since. He and his squad have been in legal “limbo” for two decades, often kept in the dark by the Britain’s Ministry of Defense about the status of the various investigations. He says: “We are being scapegoated… and are subject to the whims of successive governments.” This, and years of being deployed on high-stress operations, has led to depression. He tried to commit suicide once and contemplated it again in the summer. He wrote to his lawyers: “When this latest inquiry began, I found myself spiraling downward.”

Simm believes successive governments have abused the loyalty of these men. He says the duty of care, “that wraparound provided by the system,” has been exposed as a “sham.” He also points to the fact that the ECHR affects only soldiers, as agents of the state, but has nothing to say about the actions of any terrorist group. Soldiers take an oath to defend the Crown — “the living manifestation of the good of the British people” — but now effectively work under the auspices of foreign lawyers. “It’s a breach of contract.” Simm asks if the SAS leadership is supposed to debate “every tenet and variation” of Article 2 amid chaos and the smell of cordite, when a nanosecond’s hesitation could mean getting shot or blown up. He says the lawyers have “legalized our work to death:” the absurd, but logical, outcome will be SAS soldiers lawyering up to vet their orders before accepting a mission.

Simm broke cover last month, writing a letter to the Times of London, along with two former SAS officers. One was Jamie Lowther — Pinkerton, who left the SAS to become private secretary to William, Kate and Harry. He tells me the pursuit of some veterans is the military equivalent of the Post Office scandal, with Simm cast in the role of Alan Bates. Stories of SAS soldiers being “dragged back to be screamed at in interview rooms” are “flying around the canteens now.” He hears from soldiers who feel like “the good guys have become the bad guys — and the bad guys are now the good guys.” Lowther-Pinkerton says the effect on recruiting could be dire. The SAS see what happened to the Met’s armed police unit, SO19, which used to get thousands of applications to join. There were apparently just six after a police sergeant was prosecuted for shooting the London gangster Chris Kaba.

There’s little chance of limiting the ECHR’s reach with this government of the lawyers, by the lawyers

Lowther-Pinkerton is angry and a little ashamed that people high up the chain of command, who once dished out “slaps on the back,” will not step from the shadows to defend the “poor buggers” who were the tip of the spear. Colonel Richard Williams, who commanded the regiment on operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, is speaking up. He says people should be “fighting very, very hard” against the “utterly ridiculous” idea that putting an SAS team on the ground in some failed state automatically extends British jurisdiction and the reach of the ECHR — with legal action under Article 2 possible many years later. The politicians should not put the SAS in a position “where the risk to my life is matched by the risk to my liberty.”

Colonel Williams says SAS squads are not “mad dog” assassins. “Special Forces are not above the law. Full stop.” But he says they need to “have the freedoms to execute important actions on behalf of the state.” After 9/11, the regiment was sent to dangerous places to capture terrorist suspects who might know about the next attack, along the way losing “a lot of people wounded, a lot of people killed, relative to our small size.” Soldiers will be prepared to do that, he says, only when they think their actions — “if they’re good actions” — are protected under the law. The alternative is bombing from the air, which — as Williams points out — obliterates the intelligence and risks killing civilians.

This is what’s happening, but it has more to do with another effect of the ECHR: it can make arresting terrorist suspects next to impossible. In December 2022, the British government learned about an Islamic State biological weapons engineer, a Yemeni, based in a village in northern Syria. His phone and computer may well have had the names of others in his network, or plans for an attack. But if troops had been used to seize this digital record, they would not have been able to detain the man himself. They would have had to let him go even if he’d surrendered. The ECHR makes it illegal to hand over terrorist suspects to Syria, because of the risk of torture, and illegal to take them to Britain because there’s no extradition treaty. So an RAF Reaper drone sent two hellfire missiles down to kill the man.

Ben Wallace ordered many such strikes in his time as defense secretary. This was a “frustrating” outcome. In many cases, he would have liked a trial in the UK “rather than making those who seek to do us harm into martyrs.” Wallace says his options were often narrowed to a drone strike when the Ministry of Defence’s lawyers said a terrorist suspect could not be “rendered” across an international border, or handed to the government of somewhere like Syria: “We simply could not put British personnel into that position on the ground. The only option therefore to stop the threat was often a kinetic strike.”

Wallace says that the “aggressive” nature of the European Court of Human Rights is starting to retrospectively turn military operations into police operations. This creates an opening for lawyers such as the notorious Phil Shiner, convicted of fraud over claims against British soldiers in Iraq. In fact, he says the ECHR creates contradictory obligations because it asserts primacy over the Geneva Conventions, the historic rules of war. It is “vital” for parliament to reverse this “if we are to ensure we can deal with the emerging threats to this country.” The European Court “has no business unilaterally asserting itself over UN deployments or deployments outside of Europe.”

There’s little chance of anything limiting the ECHR’s reach with this government of the lawyers, by the lawyers, and for the lawyers. And the timing is terrible for a campaign by SAS veterans. The Haddon-Cave Inquiry is hearing claims that SAS soldiers in Afghanistan carried out extra-judicial killings. Lawyers for the Afghans argue that the inquiry would never have happened without Article 2 of the ECHR. The SAS veterans say they don’t necessarily want Britain to leave the ECHR, but they would like the government of the day to use powers in the convention to suspend Article 2 — the right to life — during war or national emergency.

Simm repeats a saying variously attributed to Orwell, Churchill or Kipling: “We sleep soundly in our beds because rough men stand ready in the night to visit violence on those who would do us harm.” One day, those men may not be there when we turn to them for help.

Paul joins The Spectator’s Edition podcast to discuss further alongside Colonel Richard Williams, a former SAS commanding officer in Iraq and Afghanistan