For the second time since fighting began on September 27, a humanitarian ceasefire was agreed between the warring countries of Azerbaijan and Armenia — and, for the second time, it was quickly broken.

Momentum is now firmly in Azerbaijan’s favor, with Azeri forces capturing a number of towns and settlements in the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh. These could subsequently be used to launch an assault on the capital, Stepanakert, which has already come under multiple bouts of artillery fire. Armenia has retaliated with long-range bombardments of its own against Azerbaijan’s second city of Ganja, an act that has caused outrage in Baku as the city is comfortably outside the disputed territory.

An attack on Stepanakert (a densely-populated city of 55,000 people) would be a bloody business for both the attackers and defenders, but it appears that it can now only be prevented by an internationally-arbitrated peace settlement — and nothing so far has suggested one will be accepted, let alone enforced.

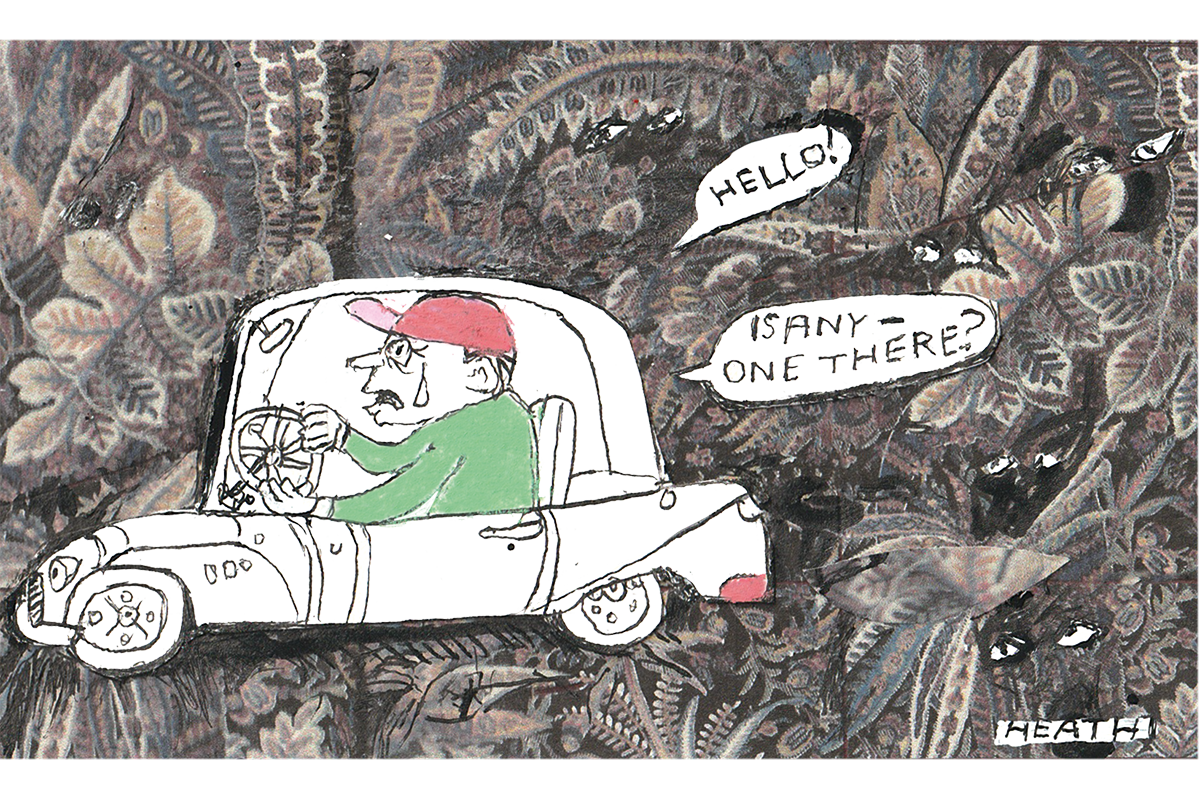

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s Minsk Group — created in 1992 to try and peacefully end the first war over Nagorno-Karabakh — has utterly failed to bring Yerevan and Baku to terms. Of the principal members, only France and Russia have made any strident attempts to end the violence. But Azerbaijan has bluntly stated that the positions of both Moscow and Paris are too favorable towards its Armenian enemies. Indeed, Russia and Armenia have been close political partners since the collapse of the Soviet Union, while President Macron seemed to suggest that this latest conflict had been started by Baku. The US, meanwhile, remains embroiled in its myriad of domestic issues, not least the presidential election, and has done little beyond calling for a ceasefire.

Azerbaijan has every reason to feel confident. Along with a threefold advantage in manpower, its economic muscle is far greater than Armenia’s, largely as a result of Baku being home to oil and gas pipelines originating in the Caspian Sea. This has allowed it to modernize its military, with purchases of extensive quantities of equipment and weapons from foreign suppliers. Israel has been chief amongst these, supplying Azerbaijan with drones that its forces have used to devastating effect in the ongoing war. Armenia, using mainly Soviet-era weaponry, has struggled to counter its enemy’s use of UAV reconnaissance and guided artillery strikes.

It is not only in equipment that Azerbaijan has an advantage since its forces have benefited from foreign training. The US has provided approximately $20 million in training packages for Azerbaijani forces, largely due to America’s interest in Baku’s pipelines, as these are the only natural resources from the Caspian not under either Russian or Iranian control. (Neighboring Georgia, which is home to the middle section of the pipelines, has also benefited from substantial US military aid, but this is also due to Georgia’s commitment to Nato operations in Afghanistan). Armenia, meanwhile, has received little in comparison, as it remains in Russia’s sphere of influence.

Yet Azerbaijan’s greatest asset is perhaps the unequivocal support of Turkey. Coupled with the fact that the UN recognizes Nagorno-Karabakh as belonging to Azerbaijan, as well as the inability to substantially refute Baku’s claim that Armenia fired first, Azeri President Ilham Aliyev is — for now — in a relatively strong position. Even if his forces suffer a catastrophic military reversal (which appears unlikely), Azerbaijan can almost certainly count on Turkish military support if needed.

Other countries have expressed ‘concern’ and called for a return to the negotiating table (a diplomatic gambit as common as it is ineffective), but it is the man in the Kremlin who will be feeling the most pressure.

The longer the conflict drags on, the more complicated Russia’s position becomes. Although President Putin is no great fan of the incumbent government in Armenia (which deposed the Kremlin-aligned Sargsyan administration in a 2018 revolution), for the sake of Russia’s strategic interests in the South Caucasus, he cannot be seen to abandon Armenia completely. Azerbaijan, while on relatively good terms with Moscow, puts both Turkey and the West higher on its international friend list. Meanwhile, Georgia — a staunch ally of the US and Europe — is hostile towards Russia.

Currently, Russia’s line is that it will not interfere unless the violence extends into Armenia proper, which would force Moscow to honor its mutual defense pact with Yerevan. Yet the Kremlin will also have its eyes on domestic matters: along with losing its foothold in the South Caucasus, refusing to send substantial aid could cause discontent among the sizable Armenian community in Russia. Putin does not want to give any of his citizens greater reason to think that Alexei Navalny’s growing opposition movement may be a viable alternative to his government. Meanwhile, failure to act risks upsetting Russian hawks — those who have traditionally lent their support to Putin in return for perceived Russian strength on the world stage.

Abandoning the Armenian cause also runs the risk of triggering a shift in Yerevan’s foreign policy. Moscow might have originally hoped that Prime Minister Pashinyan’s government would collapse in the wake of a short, sharp and disastrous war. But the longer the fighting drags on, the more likely it is that a lack of Russian aid — and not the Pashinyan administration — would be blamed for an Armenian defeat. Already Pashinyan expressed overtures for closer relations with Europe (which have incurred angry murmurs from Moscow), but a perceived betrayal could push Yerevan into the arms of Brussels and Washington. Armenians may even look to their northern border, and notice that Georgia — with its billions in foreign investment, visa-free travel to the EU, and increasingly ‘first world’ cities — has fared rather well in its Western alignment. Moscow cannot afford to risk Armenia going the way of Georgia.

Direct military support would cause a major rift between Russia and Turkey — perhaps even leading to clashes — but the practical aspects would also make any Russian senior officer grimace at the prospect. Georgia stands between Russia and Armenia, and although a fast, aggressive strike through Georgia and into Armenia might be possible in theory, it could easily become a drawn-out and highly bloody affair. Moving troops and equipment by air or the Caspian Sea (and presumably via Iran controlled waters) would come with their own lengthy complications.

[special_offer]

Of course, this would constitute an extreme turn of events — if Russia is considering a military confrontation with Turkey then even COVID-19 might be pushed off the front pages. But if Azerbaijan wins and takes Nagorno-Karabakh, the humanitarian repercussions could be severe.

Although Baku has promised the current ethnic Armenian residents of the region full Azerbaijani citizenship and protection under its constitution, it would be an act of utopian naivety to imagine that Azerbaijanis returning to the area — who themselves were the victims of forced expulsions in the 1990s — will live peacefully with their new Armenian neighbors. For their part, the Armenian authorities are drawing comparisons with the Ottoman Empire’s genocide of the Armenian people in the early 20th century: with reports of Armenian prisoners of war being executed and accusations of Baku employing Islamist mercenaries, the echoes of the Armenian people’s past are becoming increasingly loud.

With the rest of the world oblivious, apathetic, or ineffectual, Russia faces some difficult choices with few attractive consequences. The best that Moscow (and Yerevan) can hope for is a rapidly negotiated peace. But while Azerbaijan is winning and Turkey offers unconditional support, expectations of a lasting end to the hostilities are as likely as a post-war harmonious coexistence.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.