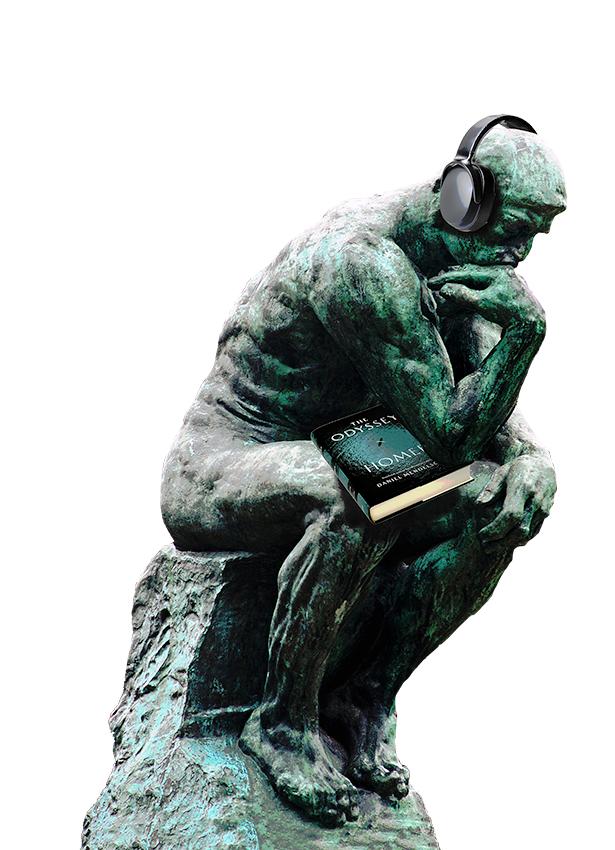

Homer goes right at it: “Sing Goddess, the Rage of Achilles.” Adapted to our times: “Sing, Bragg, your rage against the Trumpies.”

Alvin Bragg, who grew up in a section of Harlem aptly named Striver’s Row, is by most accounts one angry man. Since he was elected New York County’s district attorney in 2021, he has set himself to punishing the city for what he takes to be generations of wrongful prosecution of black offenders — and incidentally most other lawbreakers. His policy writ large has been to treat all felonies as misdemeanors, which are promptly dismissed.

He occasionally compromises in favor of prosecution but only if the crime has aroused a special level of public outrage. Bragg’s tenderheartedness towards criminals, however, has limits. When it comes to Donald J. Trump, Bragg appears ready to emulate famed Texas lawman Judge Roy Bean, who handed out verdicts with a rope. Alas, in this case, Bragg hasn’t been able to find a justiciable case. The roistering Trump once paid the gamesome Stormy Daniels to play mum about their frolics (which he says never happened). Only by building a bridge of conjecture, hypothesis and ad hominem does Bragg attempt to find something to indict.

But the real story here is not the maybe-maybe-not case; it is the tune the Goddess is still singing. The anti-Trumpians cannot exorcize the anger that possesses them, which I take to be only the perfected form of the psychological fragility that is now endemic in America. Indignation: we can’t get enough of it. I know I can’t. Mine is reserved for vaccine makers, public health officials, perpetrators of climate change hysteria, 1619 propagandists and egg prices. But I will put these deeply felt grievances aside for now and turn to the vexations spray-painted more widely on the American soul.

On these, I am not a lone voice crying in the wilderness. Weeping along beside me, for example, is the New York Times‘s Ross Douthat: “American Teens Are Really Miserable. Why?” Douthat cites a CDC report that teenage girls especially feel beset by “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness.” This has happened, says Douthat, because the socially isolating smartphone has swung “like an ax” against the “hollowed-out tree” of “familial and romantic and even sexual connection.” If I follow his metaphor correctly, it is “social liberalism” (aka woke extremism) swinging the ax.

Douthat’s fellow Timesman, David Brooks, takes a similar view in a column: “The Self-Destructive Effects of Progressive Sadness.” Brooks builds his article on a study in a medical health journal about how depression differs among adolescents depending on their political beliefs. Turns out progressivism comes with a large hidden fee, and for woke girls it is even higher. “Maladaptive sadness,” says Brooks, spreads like spring pollen among those who think “The American dream is a sham, climate change is so unstoppable, systemic racism is eternal.”

Douthat and Brooks both have an eye on Jonathan Haidt, who builds on some of the same data in his Substack essay “Why the Mental Health of Liberal Girls Sank First and Fastest.” For Haidt, it is “phone-based childhood” all the way down: “Gen Z has become more external in its locus of control, and Gen Z liberals (of both sexes) have become more self-derogating.”

Matthew Yglesias, cited by Brooks, is right in there with another CDC-inspired take on “Why Are Young Liberals So Depressed?” But Yglesias bends away from smartphones and broken families to emphasize a different factor: the influence of “adult progressives, many of whom now valorize depressive affect as a sign of political commitment.” This isn’t exactly a brand new thought. To be taken seriously, generations of leftists have paraded themselves in somber hues and drawn long faces about the sorry fate of the world. They were then and are still now worth a good laugh.

Let me pile it on a little deeper. Mary Gaitskill, well-known novelist, short-story writer and visiting professor whose bleak stories have some roots in her life in the 1960s as a teenage run-away and prostitute, published a long article in the Chronicle of Higher Education alternately titled “Fear, Rage, and Anguish on America’s Happiest Campus” and “The Trials of the Young: The Kids Are Not All Right.”

Gaitskill has no statistics about who is unhappy and why, but she has a lot of experience in classes of college students who are struggling to find fictional voices for their pervasive misery. She quickly shows her Chronicle readers that she is on the right side of history. By 2021, she says, “The unhappiness was continuing its upward creep, for obvious reasons: the pandemic, the exponentially growing climate crisis, political madness culminating in the attack on the U.S. Capitol, the ever louder voice of white nationalism, the murder of George Floyd, the vicious street attacks on Asian people which seemed to loom larger and more horrible in contrast with the extra anti-racist vigilance on campus.”

But she is sufficiently adroit also to observe: “the tireless efforts by hyperconscious campus administrations to create classrooms where everyone feels safe and as few people as possible will be made ‘uncomfortable,’ let alone unhappy.” The idea that these bubblewrap approaches may themselves have something to do with students’ inability to cope never crosses her mind. No, the dangers are real, and the problem with the campus “corrective apparatus” is that it is “ineffectual and confusing.” Students learn to fling around terms such as “toxic masculinity” with no relevance to the matters at hand.

Much of Gaitskill’s essay deals with an eight-member fiction-writing class she just did on sexual assault. Out here in the off-campus world, I have to wonder whether this was the wisest thing to teach to our ax-inclined young sufferers. Her college administrators warn her that campus mental-health issues are “through the roof.” Four of her eight students wrote about suicide, two of them about their own previous attempts.

Gaitskill makes way for all this because “Fascination with murder and despair is also an essential human feature, and the young have been ever-famous for their raving misery.” She finds their “fear, anguish, and rage” appropriate to the times, especially because they “have been encouraged to believe that happiness is an expected norm,” and telling horrific stories is some form of taking control.

I happen to be among those who think that fostering expression of fantasies about rape, murder and suicide may not be the best way to educate young people, and particularly those whose mental health is a bit wobbly. But there is no doubt that Gaitskill’s essay shines a light into crevices not illuminated by the CDC, Douthat, Brooks, Haidt and Yglesias, among others.

These themes of fragility are reverberating in other interesting ways.

Suzy Welch, an NYU management professor, tells us that “Generation Z Longs for Stability.” Welch reports on a post-Covid survey of college graduates in which 85 percent said what they wanted most in employment is “stability.” The word gains its power from what it is not. Not opportunity. Not success. Not wealth. Not even happiness. I take some encouragement from that survey. In an era when many people are parading their inability to cope as badge of honor, these graduates hope to find a baseline of normality.

Wall Street Journal reporter Emily Bobrow likewise asks, “Do Trigger Warnings Help or Hurt Students?” That is, “do they actually help people emotionally prepare for challenging material?” Bobrow turns to an Australian researcher who concludes that they neither help nor harm. Basically, “they don’t seem to do anything.” But a 2020 Harvard study suggested that “trigger warnings made people feel more anxious about the material in question by encouraging them to see their trauma as more central to their life narrative.” In other words, bubblewrap.

The great dispenser of bubblewrap, of course, is the university that creates the “corrective apparatus” to spare all tuition-paying students discomfort. The Lumina Foundation has just published another study to the effect that many students choose not go to college because of “emotional stress” and that many other students “stop out” also because of emotional stress. I assume the message is aimed at college administrators who will find that relieving “stress” sounds like something they can get their arms around, as opposed to undoing demography or persuading the American middle class that overpriced degrees in useless subjects are a good “family investment.”

But plainly “emotional stress” is more a product of a culture, not a phenomenon of individual discomfort. It is what teaches children to escalate minor aggravations into crises that require therapeutic intervention, just as an excess of therapeutic intervention teaches children to be fragile. We have a perfect circle here of denouncing injustice, seeking discomfort, celebrating misery, complaining about anguish, and imposing still more injustice.

The whole tenor of our society has changed in recent years — which is the subject of my 2021 book, Wrath: America Enraged. And I find it strangely calming how the tempest-tossed waves keep crashing. We’ve adapted our system of education at every level to emphasize fear and fragility. Children are taught to believe without question that our country is racist; our institutions are rotten and always have been; other forms of oppression are rampant, including sexism, homophobia and anti-transgenderism; that the capitalist economic system is ruinous; and that environmental catastrophe and global warming will lead shortly to an apocalypse.

And we are re-staging our national political battles like a never-ending Punch-and-Judy Show. We now know that our political rumbles are mostly theater — and instructive theater at that. Sing Goddess, Bragg on. We are teaching a new generation that anger, distress and rage define the meaning of life.

“Emotional stress” is not a side-product of this ideology. It is the main product. Persuading children not to try, not to set goals and aim towards high achievement, but instead to whimper in defeat and despair is exactly the cultural message that is foremost on the educational agenda. Are we really to be surprised that among the kids who reach college age a large percentage say, “not for me,” and another large percentage say, “too hard?”