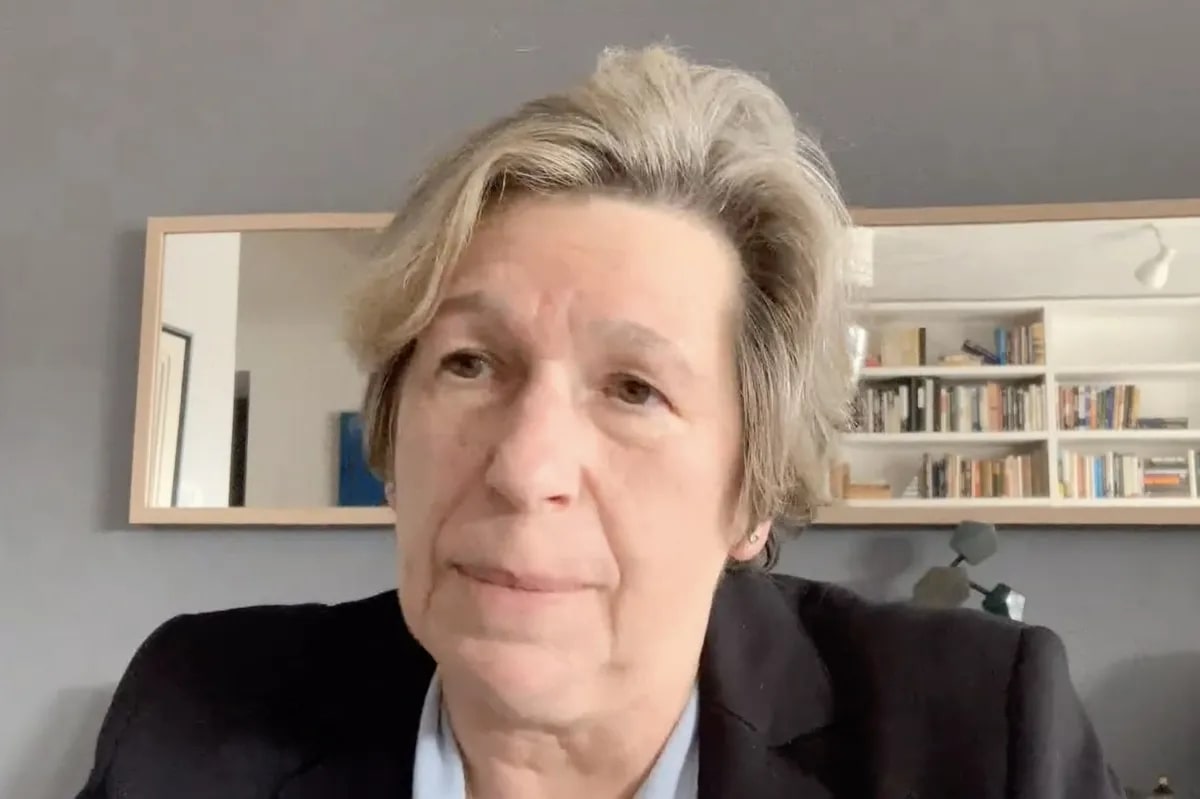

It was eerily warm in New York the day before the midterm elections, and the president of the American Federation of Teachers, Randi Weingarten — one of America’s most powerful union leaders and arguably the Democratic Party’s most influential non-elected power broker — was bracing for a confrontation that threatened to push the atmosphere past boiling point.

We were standing in front of Public School 169, in Bay Terrace, a majority-white, upper-middle-class neighborhood in Queens, where Weingarten was attending a rally for three Democratic candidates for the House of Representatives.

“You probably heard that the anti-vaxxers are going to show up,” she told me with a hint of exaggerated amusement. I hadn’t, and expressed my sympathy, since I could imagine the ugliness that might ensue. “Welcome to my world,” said Weingarten, and she hustled across the street toward the waiting politicians — and the looming trouble.

Earlier that day I had met with Weingarten in Manhattan, under less trying circumstances. But she had plenty to worry about. Accused by Republicans of having promoted Covid-19 school closures at the expense of children — a position they say was taken in the narrower health interests of her 1.7 million members — she had a lot to lose from the much-promoted “Red Wave” should it come on Election Day. If the Democrats were “the party of lockdown,” then Weingarten, as the party’s most visible public-service personality, would lose a lot of prestige, given that the AFT had contributed at least $3.24 million to Democratic candidates in the 2022 election cycle and roughly $15 million to Democrat-sympathizing super-PACs and the like. Indeed, when I first interviewed her in the relative calm of the Upper West Side, she seemed to be preparing for defeat in her deep-blue fiefdom of New York State (she is the former president of the AFT’s largest local, the United Federation of Teachers).

Outside the entrance to the subway station at 72nd and Broadway stood Democratic gubernatorial incumbent Kathy Hochul — governor only because of Andrew Cuomo’s resignation, and by all reports sinking in the polls. She was generating little enthusiasm among passersby, despite the smattering of teachers’ union members wearing blue-and-white T-shirts that proclaimed “AFT votes.”

I didn’t get an exact count, but the turnout of interested citizens wasn’t visibly greater than the number of TV cameramen and soundmen crowding around Hochul, who, after a good deal of smiling and waving for the scrumming media, quipped, “Unless you’re all voting for me you have to get away.”

But there weren’t many ordinary voters to meet, and after posing for pictures with the governor — Hochul smartly dressed in a tan pantsuit and Weingarten clad in black pants and a black jacket over the union T-shirt — the labor leader found herself with more time to talk with me than she probably wanted. When I asked her what it would mean if the Deocrats, against most predictions, held on to their slim majority in the House, she seemed to contemplate what appeared at that moment to be the more plausible scenario: a Republican takeover of both the House and Senate, and a come-from-behind victory for Republican Lee Zeldin over Hochul. By some measures a Zeldin win would be the most embarrassing result for the Democrats, since the congressman for deep-red eastern Long Island had thrown in with Trump and voted against certification of the last presidential election.

“Look,” said an unusually muted Weingarten, “clearly I’ve been a Democrat my whole life. But I’ve also supported Republicans like [Senator] Jake Javits, [Governor] George Pataki, others, and I think it’s really important to have two parties who actually believe in democracy, who fight out the issues… I think that if the Democrats, by chance, hold the House, it will be because of the [Republican] extremism, and while people normally vote their pocketbooks, you don’t actually have a good economy that you can rely on for working folks if you don’t have a viable democracy… But people feel terrible, and I think that we, only in a few years, will find out the true effects of Covid… the mental-health effects. The being alone, the being dislocated, the disaffection. I think that that frankly is the long-term effect of Covid, the anxiety, the anger and, frankly, the exploitation of that anger… We’re living in a post-truth society, and so the number of clicks on Twitter or the number of clicks that people get in terms of eyeballs on things, conspiracy theories, it’s very dangerous.”

I found it interesting, even seductive, that a labor leader would be so psychological in her political analysis — an analysis with which I partially agreed. But what I really admired was her tactical skill: she was moving me away from the touchy subject of her successful lobbying, in February 2021, of Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, not to reduce recommended social distancing between students from six feet to three feet, which Walensky privately favored. The result of Weingarten’s pressure was to make it harder for schools to reopen, increasing isolation and alienation not only for the young but also for those AFT members who wanted to keep teaching in person. Weingarten acknowledged that inflation and crime were also big issues, but the party line appeared to be Covid alienation and Republican “extremism” — and she stuck to it throughout our interview.

The Upper West Side of Manhattan was a good place to talk quietly because one doesn’t often run into anti-vaxxers or Trump supporters. Weingarten made a game attempt to hand a Hochul campaign flyer to a Covid-masked man with gray hair, a T-shirt and blue jeans, who looked at it indifferently and kept his hands in his pockets. “You know New Yorkers,” she said, and then she left for a Democratic phone-bank event in suburban Suffolk County, Long Island, deep in Zeldin territory.

That afternoon, in usually Democratic Queens, however, Weingarten seemed to be in a safer place and a more hopeful mood. PS 169 is a unionized elementary school with about 350 students, but it also houses a special Bell Academy Middle School, where the class sizes are smaller than average and the students wear uniforms.

If standing just outside a school, among AFT officials, was Weingarten’s safe space, the narrow strip across 212th Street with the blue AFT backdrop was not. As a handful of sign-brandishing anti-vaxxers approached the T-shirted AFT group on a sliver of grass, Weingarten forthrightly moved to engage them, which seemed unwise when the demonstrators shouted, among other things, “They will kill your children by forcing a Covid-19 vax,” “Healthy boys are dropping dead,” and “Vote red if you want to bring down pharma.”

There was no spokesperson, but Rita Palma, who told me she was from “out east” in Suffolk County, seemed to be a leader of sorts, and she wasn’t having any of Weingarten’s diplomacy. “You’re on the wrong side of history, Weingarten,” she bellowed. “I’d get it over with and do your fake rally, and tomorrow’s coming and you’ll see.” Presumably that meant a red wave, since Palma was carrying a Zeldin sign that she turned to brandish at passing motorists. Meanwhile, a woman wearing a “No” T-shirt, who claimed she’d lost her teaching job because of vaccine mandates, came face-to-face with Weingarten: “You defend child molesters, you defend bank robbers, you defend racists, but you didn’t defend teachers with religious beliefs. Shame on you.”

In fact, Weingarten had recently appeared on an online video program with the radically anti-vax Michael Kane to reiterate her position that the AFT had always tried to “follow the science,” not force vaccine mandates, while at the same time respecting individual exceptions so that any vaccination programs during the pandemic would encourage voluntary participation by teachers.

I couldn’t hear Weingarten’s direct responses to Palma and the “No” woman because the anti-vaxxers were so much louder than she was. But when the rally got underway, the more recognizable Randi Weingarten came to the fore. Such is her political weight that Representative Hakeem Jeffries of Brooklyn, presumptive successor to Nancy Pelosi as Democratic leader in the House, had come, along with Representative Grace Meng, the 6th district congresswoman, and Robert Zimmerman, the Democratic candidate in the 3rd district. Quite a bit of firepower for only twenty or so friendlies and maybe ten hostiles. In the hierarchy of clout, though, it was hard to tell who was more important: a senior elected Democrat like Jeffries or the president of the AFT.

When the three politicians had finished speaking, Weingarten took the microphone and Jeffries led a chant: “Randi, Randi, Randi!” The anti-vaxxers almost drowned her out with jeers, but Randi shouted into the mic loud enough to be heard: “This is what democracy looks like: but the difference is this… The Democrats say let me help you and instead of doing that, you are screaming at the people who deliver!”

By now two New York City police officers had arrived, while two other tough-looking men — I presumed they were AFT security or plainclothes cops assigned to protect Jeffries and Meng — looked ready to move. The driver of a passing cement mixer, intrigued by the increasingly volatile scene, slowed down and started repeatedly honking his horn. As if Zeldin had willed it, Weingarten’s microphone suddenly went dead. Despite the chaos and the screeching of the counter-demonstrators, she handed the mike to an aide and started speaking, without amplification, directly over the taunts that included a man who declared, “God is watching!” Unfazed, Weingarten replied at the top of her voice: “One of the reasons we have this controversy right now is because we did everything we could to reopen schools for kids… At the same time, we wanted to make sure that everybody was safe!”

The statement was certainly debatable, but the anti-vaxxers weren’t interested in civil discussion. At least one of them wasn’t interested in biology, either. I had noticed a tall man on the street holding up a handmade placard stating, “Viruses Don’t Exist” and wearing a T-shirt that displayed a cartoon sheep receiving an injection. I had heard him earlier declaiming about dead children. This was too much, even for the anti-vax Palma, who at least was professional enough to carry a printed Zeldin sign. When I asked her if she knew the no-virus demonstrator, she shook her head with concern: “He’s a little off-topic.”

To paraphrase Randi Weingarten, this is what political rage looks like, though the party of the enraged didn’t wind up winning, quite. The next day, the Democrats held the Senate, barely, and Zeldin fell short of beating Hochul by about six percentage points. But by coming as close as he did, Zeldin seemed to have coattails, since four Democratic congressional seats in New York, including the defeated Zimmerman’s district, flipped to Republican, securing the new GOP majority in the House. I’m pretty sure that nobody I observed on November 7 was ready to give up fighting. Not Randi Weingarten, of course. And especially not Rita Palma, who gave me her phone number and suggested I call her out east for more information.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2023 World edition.