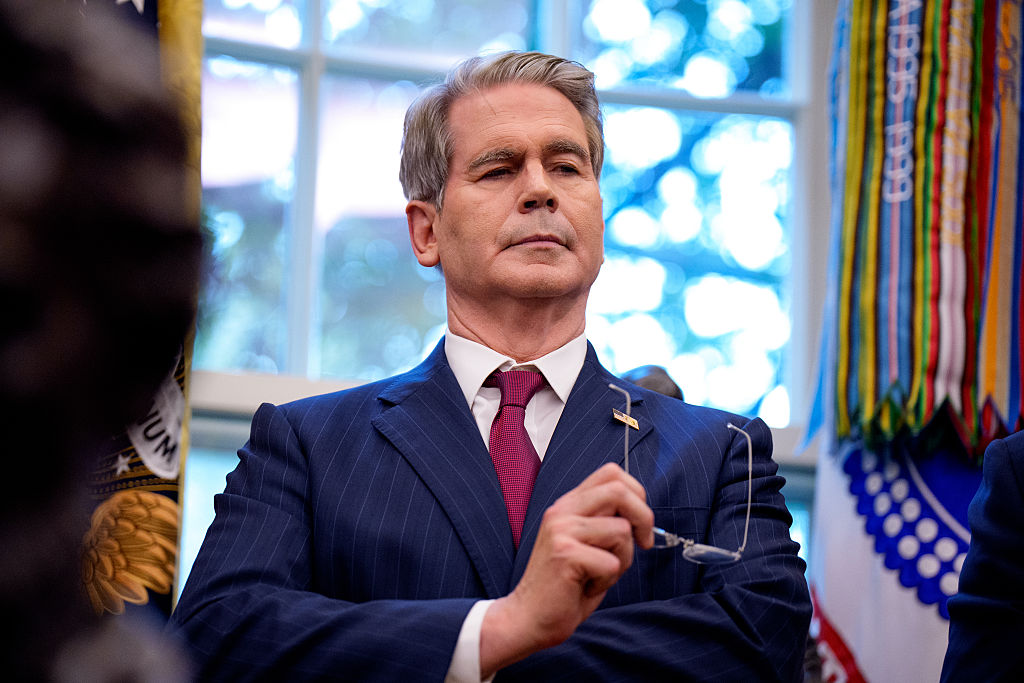

A glimpse into the mindset of Javier Milei was given by his decision this week to retweet a picture on social media depicting himself, prophet-like, gazing down from the clouds. As his flight to Italy for the G7 summit took off he would have been feeling rather smug — he had finally secured a long-awaited win back home in Argentina.

Given the protests on the streets, it is maybe surprising that Milei’s approval ratings remain so high.

His monumental “Bases Law” — which has been the subject of months of fevered debate and frantic toing and froing — has been passed “in general,” a major step towards its safe passage into the statutes’ book. It will give him wide powers to implement the “shock therapy” he promised to administer during his bombastic presidential campaign. No president in the post-dictatorship history of South America’s second-largest economy has gone longer without passing a law — and supporters had feared that failure to secure this bill’s passing could have signaled the death-knell for his government.

As lawmakers debated the bill on Wednesday in Buenos Aires, a peaceful protest turned violent as darkness fell outside the parliament. Cars were set ablaze, Molotov cocktails were thrown and battalions of riot police peppered tear gas and rubber bullets to suppress the unrest. Five opposition members of congress and nine police officers were reportedly hospitalized amid the chaos. Such passionate opposition is a reminder that, for all the western rhetoric that Milei is successfully turning the oil tanker around, life for ordinary Argentines has become harder.

True, monthly inflation has fallen to 4.2 per cent, its lowest level for two years. True, the country ran a budget surplus for a whole quarter for the first time in more than a decade. But the Milei administration’s severe austerity measures have pushed annual inflation to nearly 300 percent. Unemployment has soared as tens of thousands of government workers have been laid off. More than half of the country —!some 55 percent — are now living in poverty, a sharp increase, and the number of people living in “destitution” is now at nearly one in five. The evidence for these changing circumstances can be seen in the growing number of rough sleepers in the capital.

Given this reality on the streets, and the so-far glacial pace of his legislative agenda, it is perhaps surprising that Milei’s approval ratings remain so high. One poll last month suggested that 54 percent of Argentines approve of his government, meaning his level of support has remained steady since his election victory last November. This can largely be put down to the frustration many everyday Argentines feel regarding the way the country’s economy has been steered into an iceberg. The ship Milei inherited was already sinking and his countrymen’s shock decision to elect a chainsaw-wielding maverick with no political experience was interpreted as the last throw of the dice of a population desperate for change. This strong position means his supporters are willing to give him some slack.

Similarly, Milei has been brutally honest with the country about the situation it is in. At his inauguration speech in September he warned that things would get worse before they get better — and so the current crisis has perhaps already been priced in by the public. “No hay plata” (there is no money) has become the rallying cry of his supporters. The passing, at long last, of his Bases Law gives Milei a much-needed boost, and will convince his supporters, who may have been wavering in the face of economic reality, that his project is working.

The bill faced strong opposition throughout its several iterations, and even the version which has been narrowly passed is stripped of some of its proposals. The lowering of income tax thresholds to boost the tax take was scrapped for example, as was legislation to allow for the privatization of most state companies like the national airline Aerolineas Argentinas. Tax incentives for foreign companies made the cut, something seen as vital by Milei’s supporters to taking advantage of Argentina’s rich and abundant natural resources. Critics fear that opening the doors to foreign investment will lead to a steady flow of wealth overseas. Worryingly for some employees — although perhaps less so for business owners — some of the country’s incredibly strong employment laws will also be rolled back, which people fear could lead to an increase in the numbers of those out of work.

Whatever happens, Milei is likely to face strong opposition going forward. The unions, backed by the all-powerful Peronist political machine, are strong, and adept at mobilizing workers into the streets. Protests and strikes have been common since Milei’s election last year.

Beyond the economy, many Argentines have legitimate concerns about Milei’s social policies. He has called abortion “aggravated murder,” causing women’s rights campaigners to fear that the hard-won right to a termination, granted less than four years ago, could be rolled back. Some in his party, notably his vice-president Victoria Villarruel, have been criticized for seeming to downplay the atrocities carried out by the country’s 1976-83 dictatorship — a big worry in a country where many have relatives who were “disappeared.”

Despite these concerns, the passing of the law has bought Milei more time and, if the economy rebounds, these issues may fall by the wayside as Argentines see their living standards improve. One protester quoted by AFP on Wednesday, a lawyer, told the reporter that Milei’s reforms would “set [the country] back 100 years.” Given that, in the early 1900s, Argentina was one of the richest countries on the planet, that might just be the point.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply