“We can be quite sentimental about some of our so-called treasured assets,” said Lord Johnson, a UK business minister, last week. “The reality is that media and information has moved on. Clearly, most of us today don’t buy a physical newspaper or necessarily go to a traditional news source.” His implication was that it doesn’t really matter what happens to The Spectator and the Daily Telegraph, both of which were up for sale from June until this week, and that it is old-fashioned to be concerned about the state of press freedom in general. We beg to differ.

John Howard, the former prime minister of Australia, put it well when he observed recently that law, parliament and the free press are the three main components of a functioning democracy. To Thomas Jefferson, the free press was the most important factor. “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government,” he said, “I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

It is not “sentimental” to worry about Britain’s oldest weekly magazine being snapped up by the UAE

But newspapers have long been hemorrhaging readers, money and influence as people move online and get bite-sized news summaries for free. The BBC has exploited its license fee-funded status to launch free websites and become the biggest single force in the written word, as well as the spoken word. This hasn’t done much for media diversity. Newcomers such as BuzzFeed, VICE and the Huffington Post have all made valiant but ultimately unsuccessful attempts at news and agenda-setting investigations. When it comes to scrutinizing the powerful, there is no real substitute for the “traditional” media.

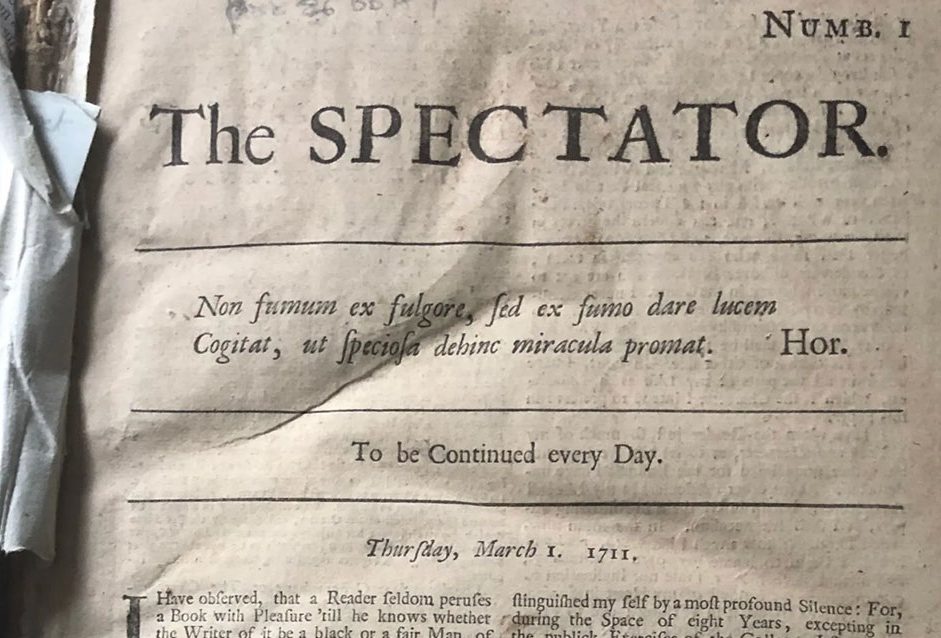

As the world’s oldest weekly, The Spectator has a longer tradition than any other magazine. We now offer daily online analysis and podcasts as well as television programs. All this has brought in new subscribers and the publication is now worth several times what it was fifteen years ago. So the magazine gathered a lot of interest when it was put up for auction by Lloyds Bank earlier this year, attracting a long list of hopeful bidders. One such was RedBird IMI, a US-based investment fund largely financed by the government of the United Arab Emirates.

It is not “sentimental” to be uncomfortable at the prospect of Britain’s leading quality newspaper and oldest weekly magazine being snapped up by the Emirates. Many have raised important questions about how editorial independence could be protected under such a move. There would need to be cast-iron assurances on this front. If no credible plan is put forward, the deal should not be approved.

It may grate with British ministers to protect the Daily Telegraph, which has specialized in revealing what they would prefer to be kept secret. From the exposé on the expenses of Members of Parliament to the “Lockdown Files” investigation into health secretary Matt Hancock’s WhatsApp messages, the newspaper’s forensic reporting has provided a great public service. It has been more prepared than other titles to confront those in power. It is vital for the health of our democracy that Britain’s most popular quality newspaper continues this important work.

There has been a trend in the last few years for politicians to pay lip service to a free press while voting for reforms that undermine it. The UK’s recently passed Online Safety Act encourages censorship on social media, which is now the main way that people read news. Ministers ought to consider the extent to which the news which Britain reads is decided by algorithms coded in California. Does that sort of foreign control matter? If they decide it does, then such companies should be obliged to disclose which articles are being targeted by their censorship bots. Transparency is urgently needed.

Then we have the Labour Party’s threat to bring in state regulation of the press. Their leader, Keir Starmer, has refused to rule this out and many in his party are actively campaigning for it. If this happens, then Britain’s 300-year-old tradition of press freedom will be replaced by a domestic censorship regime that would send a chill through all newspapers, regardless of owner. We do not hear many politicians on either bench making this point.

Changes in ownership are far from the greatest threat to journalism. A loss of confidence among the press matters too. In recent years, we have seen the bizarre phenomenon of publishers taking fright at Twitter storms and bowing to online mobs. Advertisers are sometimes persuaded to join the protest. The Spectator’s approach has been to ban any advertiser who tries to influence what we write. Our duty is to our readers.

The Spectator is in the fortunate position where revenue from readers is easily enough to cover the costs of producing our magazine. We were the first company in Britain to return the furlough payments to the taxpayer when it became clear that our readership was growing quickly enough to allow us to do so. We have no need of anyone else’s money, not even that of a new owner.

But nothing can be taken for granted, which is why any change in ownership, any tightening of regulation and any move to intensify online censorship deserves robust scrutiny. At present, no laws interfere with Britain’s free press, but no laws protect it either. More farsighted ministers will recognize that defending this freedom — whether from intrusive regulation or any other threat — is not to be sentimental but is vital to the health of British society and democracy.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply