, we hardly knew ye. And we might add that what we did know did not leave us pining for more. Swalwell, a fourth-term congressman from California, became the first candidate to drop out of the Democratic primary last month, citing his poll numbers, which were hovering around zero percent. He’ll be remembered mostly for the armory of rakes that he upended into his own face, from his Twitter push poll on banning ‘assault weapons’ that’s still recording a sizable pro-gun majority to the awkward silence that greeted his ‘I’ll be bold without the bull!’ campaign motto to his informing CNN that they might have to leave Georgia over the state’s new abortion law.

The Swalwell ‘in memoriam’ reel will be short: four seconds, maybe, of video montage while ‘Hallelujah’ by Jeff Buckley plays in the background. Yet a fundamental question still hangs in the air: why did Swalwell, doomed from the start, ever run for president in the first place? And a corollary: why do more than half of these people — even without Swalwell, the Democratic field is still some 24 strong, as Tom Steyer has jumped in since — think they belong on a presidential debate stage? Certainly some of them have claims to competence, or at least evoke curiosity. Joe Biden is a former vice president and before that had served in the Senate for decades. Elizabeth Warren has some genuinely interesting ideas, even if her adventures in Native American genetics are the sort of thing that inspire PTSD in the culture war. Tulsi Gabbard is brilliant on foreign policy. Andrew Yang gets us thinking about the perils of automation.

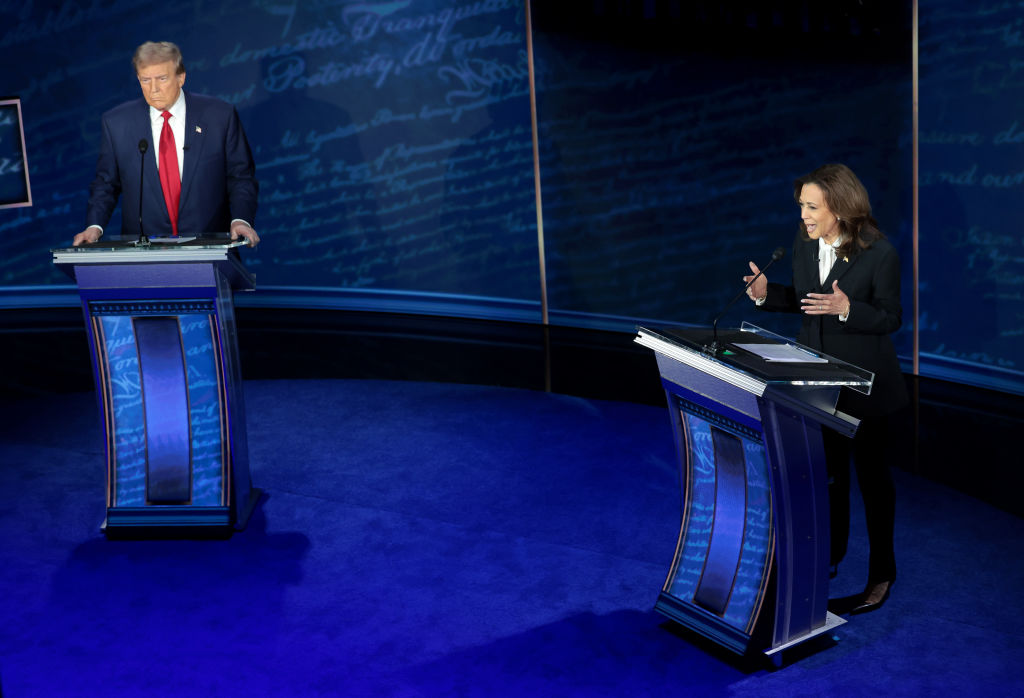

But what of the others? Marianne Williamson might have a weirdly aphoristic Twitter account, but her background is in self-help spirituality, not governance. Kamala Harris is a first-term senator adept at the ‘clap-back,’ not an especially coveted skill when it comes to commanding a military, and beyond that is known for little except the vast numbers of people she’s thrown in prison. Beto O’Rourke lost a Senate race to a Ferengi. Yes, we were all told in kindergarten that in America anyone can be president, but surely that was before Wayne Messam made his presence known. Anyway, on the masochism scale, running for president falls somewhere between hopping over hot coals and self-inflicted Persian Scaphism, given the scrutiny and reanimation of closet skeletons involved. So why are so many getting in line?

The answer, I think, has to do with the nature of the modern presidency and the contradictory way that we’ve come both to revere it and devalue it. On one hand, we venerate our presidents, elevating them into, as Gene Healy has written, ‘America’s shrink, a social worker, our very own national talk show host…the Supreme Warlord of the Earth.’ The occupant of the White House becomes a national avatar, imbued with the shamanistic power to heal all that ails. On the other hand, we’ve also drained the presidency of most of its mystique. Today’s presidents, we insist, must be just like us, fans of cheeseburgers and sharers of memes, with whatever sense of distance there might have been between us and them erased to nothing. ‘F—ck Trump,’ our daringly original late-night comedians sing in unison, and it hardly seems like a sacrilege anymore, if even a discourtesy.

There was, before the instantly polarizing Trump at least, almost a vestigial sacrifice quality to it all. New presidents were welcomed in, dressed up, showered with adulation — and then slaughtered like Iphigenia the second something called ‘voter fatigue’ set in. But however you chronologize it, there’s a common denominator beneath both this veneration and debasement of the presidency: enormous fame. The president is one of the most known personalities in America today, subjected to fierce and constant exposure well beyond the dry newspaper copy and fireside chats of yore. And if Americans have pioneered one thing in the 21st century, it’s how to monetize fame — and not just fame, but attention, with every second of our day competed for viciously by data-crunching online advertisers. The president, because we’ve made him omnipresent, thus has tremendous money-making potential. That’s why even the obsessively anti-Trump CNN can’t seem to take its eyes off of The Donald: he moves product, just as Obama did for Fox News.

We’ve turned the presidency into a business, and it makes sense that it isn’t just the middlemen who want to cash in. Anyone who stands on a presidential debate stage is instantly going to see a surge in name recognition, and therefore a boost in Google searches, hash tags, TV appearances, book deals, all the foolproof metrics we’ve come up with to measure a man’s worth. The campaign trail has become Presidency Inc., an opportunity for shrewd self-entrepreneurship. Hence the Swalwell. Yes, he’s an asterisk to a footnote, but we’re still sitting here talking about him, aren’t we? He’s a quantity now; he has lots of Twitter followers, which is how you get into heaven. And many of the others will be quantities, too, after the 12 scheduled Democratic primary debates<, the trade shows of Presidency Inc. Problem is, in such a crowded market, you need to stand out, and that means pandering to your customer base, in this case far-left progressives. Thus someone named Jay Inslee is already threatening to nominate woke soccer star Megan Rapinoe to be his secretary of state. And it’s only August.

The irony here is that Democrats are succumbing to a problem that they’ve diagnosed accurately. Money really does play too big a role in politics today, as anyone who’s ever seen a congressman frantically dialing for dollars while pulling into his child’s daycare center well knows. This isn’t necessarily a problem of capitalism. To argue that free markets must lead to the total corporatization of politics is to accept so much determinism as to sound silly. The heart of the matter seems paradoxically narrower and broader: commodification, the slapping of a price tag on everything, the inability to cordon off an area of our lives where commerce can’t intrude. And since elections have become commerce, that also means being unable to escape federal politics, the very antithesis of what the American experiment was established to achieve.

It isn’t a sign of national health when you have this many pygmies clamoring for its highest office, no matter how much our egalitarianism tempts us to think otherwise. If politics and profitable celebrity drift together, and the former is subordinated to the latter, then the presidency becomes a mere stepping stone to fame. And that right there is the end of the republic. What to do? The ideal solution would be to elect a president with fanatical, almost committable levels of self-loathing. This person would be so terrified over the very idea of developing a personal brand that he would immediately delegate most of his authority down to the state and local levels and go into hiding. A neurotic and less radio-savvy Calvin Coolidge — that’ll deglamorize the office. At least then the White House would stop doing so much of what it usually does, like meddling with school lunches until croutons are being rationed.

Alas such a person is entirely notional. And while some new campaign finance laws and internal party reforms might do the trick, I think ultimately we’re working on tougher terrain here: that of the national heart. It’s no coincidence that Presidency Inc. has risen in conjunction with the democratization of our politics, as both insist on vast exposure to the masses. If we want this to stop, then we need to decide that governance should be something apart from the Snapchat glare, something more serious, even boring, something we’re not afraid both to respect and to ignore. In the meantime, we’re stuck in a world where we know who Eric Swalwell is and must somehow learn to carry on. Bonam fortunam.