Paul Ryan is only the fourth Republican to serve as speaker of the House of Representatives since 1956. When Ryan took up the gavel, what precedent was there for a successful Republican speakership in modern times? Absolutely none. And at the end of Ryan’s brief tenure—barely beyond three years, Oct. 2015 to Jan. 2019, if he stays the course—there still won’t be one.

The congressional GOP is somehow both wild and passive: ideologically rigid yet utterly incapable of achieving the results that conservatives want. Ryan’s predecessor, John Boehner, resigned once he realised this. In retirement, he’s taken up a cause that’s far more interesting that any policy he pursued as speaker: he’s joined the board of a company that invests in “the cannabis industry” (as its website puts it) and supports the drug’s effective decriminalisation. If social conservatives are disappointed, they can at least be grateful that Boehner’s political afterlife is more wholesome than Denny Hastert’s. This one doesn’t involve revelations of sexually abusing underage boys and a felony conviction for buying a victim’s silence.

Sleaze and hypocrisy were important in bringing down Hastert’s speakership, as they had been in bringing down Newt Gingrich’s eight years earlier. But policy, including foreign policy, was the larger part of Hastert’s undoing. His Republican Congress expanded entitlements and put the lie to the party’s claims to stand for limited government and fiscal discipline. His Republicans turned budget surpluses into deficits and backed to the hilt the democratic imperialism of George W. Bush. The voters rendered their verdict in November 2006.

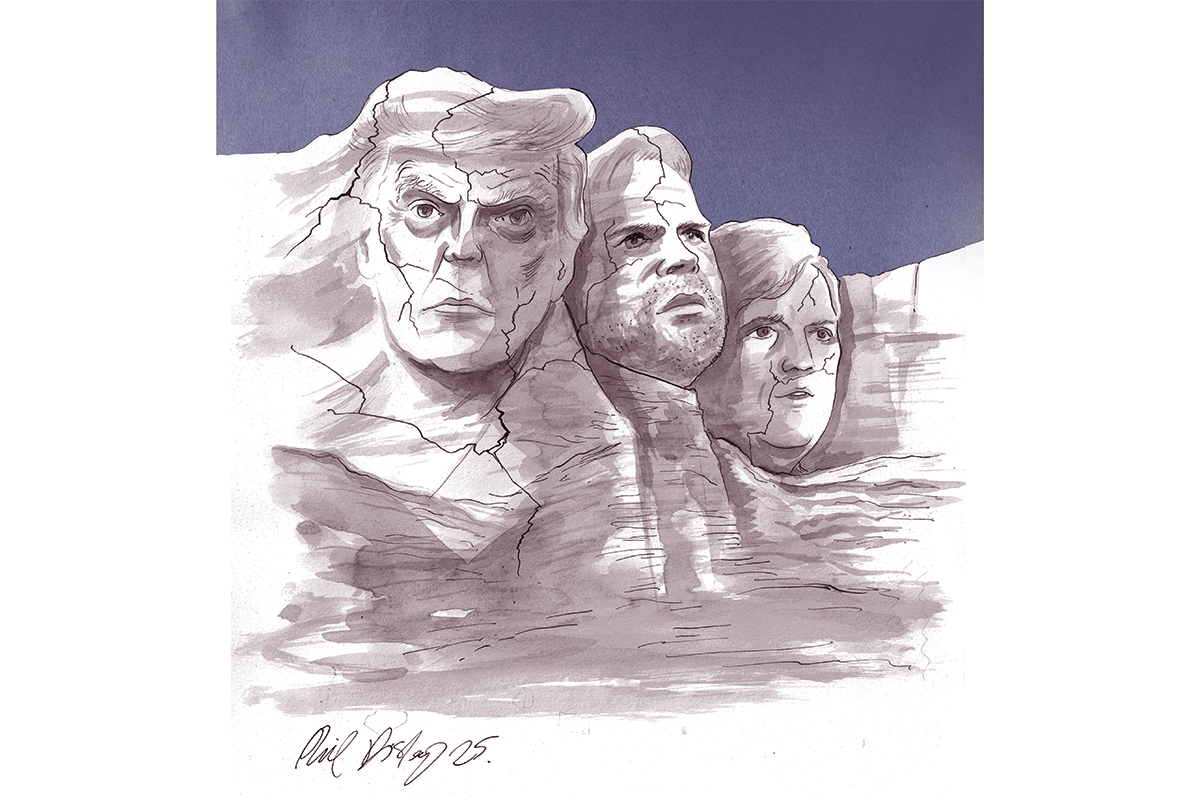

Paul Ryan entered Congress the year Hastert became speaker—1999. He was a Bush-Hastert-era Republican, but once that vintage was discredited, he became the Messiah of Republican “reform.” In practice, reform looked a lot like repackaging. Ryan was notable not for any particular idea but for being a straight-down-the-line reliable orthodox conservative Republican, which is to say, a Bush-Hastert Republican without the sex scandals and over-investment in foreign policy. Ryan represented no change at all. The GOP had learned nothing from its drubbings in 2006 and 2008. Mitt Romney’s nomination in 2012 confirmed that, and it was only fitting that Paul Ryan should Romney’s running mate.

What was remarkable about Republican reform was how unreformed it was. But grassroots Republicans demanded something more than the recycling of conservative platitudes. They despised Boehner as a sellout. And they came to despise Paul Ryan as a fake. He was the anti-Trump, a politician who apparently checked all of the correct policy boxes for conservatives, yet never gave the right the impression that he was on its side. Trump could be heterodox in a thousand different ways, but he connected with the hearts of voters who wanted a Republican who would break with the legacies of the Bushes and Clintons, not merely administer the welfare-warfare state in a more business-friendly manner.

Paul Ryan’s speakership would have been endangered in the long run by the same forces—and by the same libertarian-minded Freedom Caucus—that cowed Boehner into retirement. But Donald Trump arrived seemingly out of nowhere and smashed the “reformed” Bush-Hastert party from another direction. Ryan could hold on to his speakership last year, but the dream of returning to the halcyon days of 2002, with a supposedly normal Republican president and a Republican Congress whose failures did not lead to grassroots revolt, was dead. And the prospect of the GOP losing its majority come November loomed all too clear. Why fight for the privilege of leading the House minority, especially if it’s a fight you would lose?

So Paul Ryan is out, and a new congressional Republican Party is waiting to be born. It will need a new sort of speaker if it ever acquires a majority— a leader who can undo the structural damage wrought by Gingrich when he altered the traditional operations of Congress’s committees, and one who can reconcile elite policy with the demands of the base. It might be a long time coming.