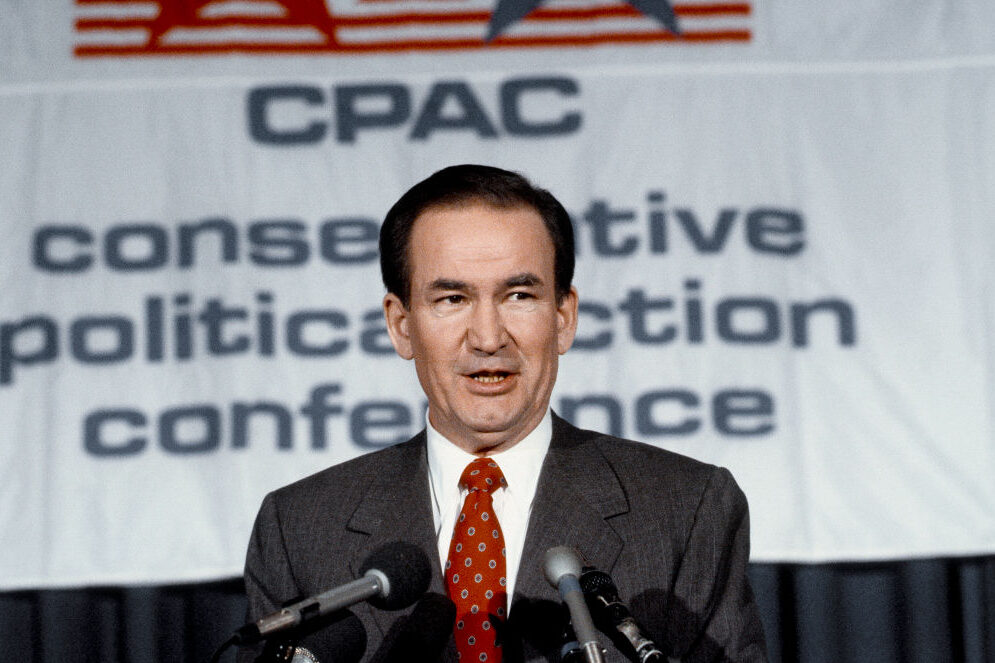

Pat Buchanan recently ended his syndicated column, essentially completing his retirement from public life. Yet it’s hard to think of any writer in his or her prime today whose ideas enjoy the currency that Buchanan’s now do. From trade and foreign policy to immigration and the “culture war” — a term that Buchanan introduced into popular politics — views that once set Buchanan apart from his fellow conservatives are now redefining the right.

Buchanan was not the only conservative skeptic of free trade or foreign interventionism in the 1990s, but he was the only one that most newspaper-reading or cable news-watching voters knew about. At the zenith of American power and economic globalization, Buchanan defined the opposition to the spirit of the age. This made him a curiosity and something of a pariah in the more respectable precincts of the center-right.

Before he came out against the Persian Gulf War in 1990 and challenged President George H.W. Bush for the Republican nomination in 1992, Buchanan was perhaps the single biggest name in conservative media. He was the closest thing to a new William F. Buckley Jr. Like Buckley, Buchanan seemed equally potent as a writer — of books as well as columns — and a television personality. He was one of the original hosts of Crossfire, a ratings smash for the fledgling CNN.

Add Buchanan’s political experience in the Nixon and Reagan administrations, and he seemed a perfect role model for conservatives who wished to combine power and ideas through the arts of language. His blend of intelligence, experience and popular appeal could easily have made him the prime ideological spokesman for conservatism in the 1990s.

But only if he’d been willing to say what the institutional gatekeepers of conservative orthodoxy wanted him to say. Instead, Buchanan defied them on trade and immigration, calling for the protection of blue-collar jobs and stricter control of the border. And he took a firm stand against the foreign policy of the George H.W. Bush administration and the rising influence of neoconservative thought within the GOP.

Buchanan was in touch with the Republican base on cultural issues and crime. And while he made permanent enemies by challenging Bush in 1992, Buchanan’s “culture war” speech at the Republican convention was a hit with the delegates.

Liberal pundits predictably hated it — and they wrote the first drafts of history. Once Molly Ivins and other progressives had set out a storyline that said Buchanan’s rhetoric was damaging to the Republican Party, Buchanan’s rivals within the conservative movement were happy to amplify the message. Neoconservatives who wanted the Republican Party to pursue a hawkish foreign policy recognized Buchanan as their most dangerous public enemy. He had a real chance of winning the Republican presidential nomination in 1996. Even after he lost that contest to Senator Bob Dole, Buchanan and Buchananism haunted the nightmares of the neoconservatives and those who wanted a more liberal, but imperial, American right.

The economy of the late 1990s was booming. Globalization’s promise seemed to be coming true. And while Buchanan remained opposed to war, mass immigration and free trade, few conservative institutions would even give a platform to his views. His 1998 book on trade policy, The Great Betrayal, voiced heresy worthy of excommunication in the judgment of free-market fundamentalists, while his subsequent volume on foreign policy, A Republic, Not an Empire, was the occasion for the most determined effort yet to cancel Buchanan, this time because he questioned the necessity of British and US involvement in World War Two.

He was never a stranger to controversy; his ideas were shocking enough to the establishment in both parties in the 1990s. His language, honed as an editorialist for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat at the beginning of his career and as an aide to Richard Nixon, could be even more jolting. The words that made him compulsively readable and watchable, that won him millions of voters as well as millions of viewers, also limited the likelihood that he could foster a movement, let alone win the Oval Office.

But sixteen years after Buchanan’s last campaign (when he ran as the Reform Party’s nominee for president) an even more rhetorically polarizing media figure would win the Republican nomination and the White House with a campaign featuring distinctly Buchananite themes on trade, immigration and foreign policy. Donald Trump did not get his ideas from Buchanan. When Americans looked to understand those ideas, however, Buchanan was the writer to whom they turned.

Trump staffers read Buchanan. Conservatives questioning their old convictions read Buchanan. And Americans of all stripes who wanted to understand why politics as they had known it was suddenly shattered turned to Buchanan.

The pity is that Buchanan’s warnings were not heeded twenty-five years earlier, however harsh they may have sounded. China’s rise would have been slower, America would have held onto more manufacturing jobs and the country would not have embarked on a series of futile wars in the Islamic world. A more restrained or “isolationist” America would have forced Europe to take its own security more seriously in the 1990s, before the rise of Vladimir Putin. Whether that would have averted the war now raging in Ukraine is open to question — but we know exactly where the path we did take has wound up.

The opposite of Buchanan’s politics has led to endless war, a stronger China and an increasingly divided and demoralized America. Yet all this would be still worse if Pat Buchanan had not been around to give authoritative expression to the alternative. His time has come.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.