Forget all the nuclear threats or pumped-up rhetoric, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un might just be the most boring of world leaders for one reason: he consistently tells us what he is going to do then tries to do it.

Case in point. For the last few years, Kim has been very clear about setting his agenda for the coming year in the most public of ways, letting the world know his plans. In a now annualized New Year’s Day Address, Kim in 2017 told the world he would test ICBMs — weapons that can, at least in theory, hit the US homeland. Last year, he signaled he was ready for a better relationship with South Korea and participate in the Olympics, which ended up being the foundation of the détente we see today between Pyongyang, Seoul and Washington.

But this year’s speech was a little different. Kim clearly wants to make North Korea great again, as large tracts of his remarks — delivered while dressed in a western-style suit while sitting in a comfy looking leather chair — were focused on making the economy better, just as in past years.

But no Korea watcher ditches their New Year’s Eve plans to hear the North Korean dictator talk GDP growth numbers. They want to know where nuclear talks between the Washington and Pyongyang will head next.

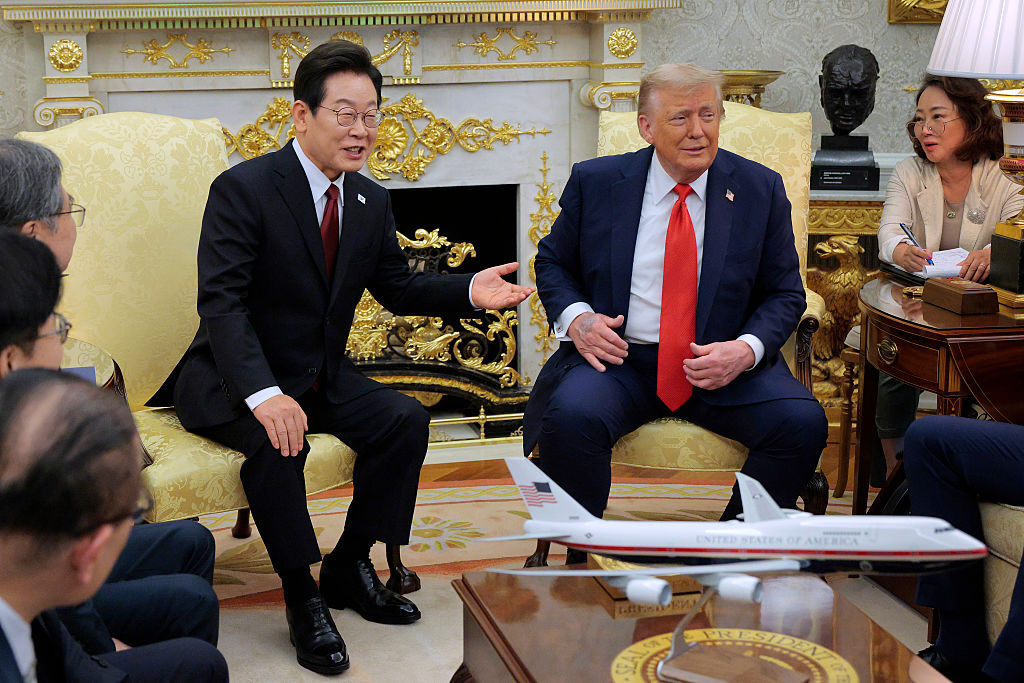

And for better or worse, Kim made himself clear once more. The North Korean leader explained he was open to another summit with US President Donald Trump, but also noted that he would not be forced unilaterally into giving up his nuclear weapons, stating once again he was looking for, as the north had referred to at least on several occasions now, ‘corresponding measures’, or some sort of benefits for giving up those nukes in an action-for-action sequence.

Kim also previewed what would happen if Washington stuck with its unrealistic negotiating position, that there would be no rewards for denuclearization until Kim’s nuclear program was eliminated. The chairman noted that he might need to peruse a ‘new way’ if Team Trump continued to pursue ‘one sided demands’. No one should be shocked that Kim has no intention of getting on all fours and surrendering his only bargaining chip with a superpower — states with ICBMs and hydrogen bombs don’t make such mistakes.

Globally media will now fixate on the meaning of ‘new way’ — likely thinking that means more missile and nuclear tests. I read that a little differently. Put yourself in Kim’s shoes: he knows that another series of aggressive long-range missile tests are optics Trump won’t be able to digest and could very well order a ‘bloody-nose strike’ to halt them. The North Korean leader wants to rule his so-called hermit kingdom for many decades but needs the economic resources and development dollars to modernize his nation.

Enter China. Kim could go to leader Xi Jinping, as he seems to already have been doing over several summits, and make the pitch that Beijing should loosen sanctions or completely drop them as Washington is being unreasonable.

Here is where Trump’s trade war could come back to haunt him. Considering that over 90 percent of North Korean exports flow through China in one way or another, Beijing has been the one to enforce Washington’s so-called maximum pressure policy, a fatal flaw that Xi will exploit if current trade negotiations look to be headed in the wrong direction. Why enforce sanctions on North Korea when America will make no concessions on tariffs, intellectual property or anything else?

If Washington was smart, it would craft a deal with the north that slowly builds a new relationship where both sides make concessions on an action-for-action basis. For example, if Kim makes small steps towards denuclearization, Pyongyang gets small amounts of sanctions relief. That seems like the best path forward. Otherwise, the Trump administration will get its worst nightmare: a nuclear armed North Korea will a growing arsenal of nuclear-tipped ICBMS and an angry China that is ready willing and able to use Pyongyang as the ultimate bargaining chip. And that would be a terrible mistake.

Harry J. Kazianis serves as Director of Defense Studies at the National Interest.