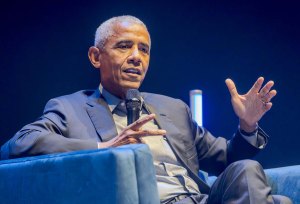

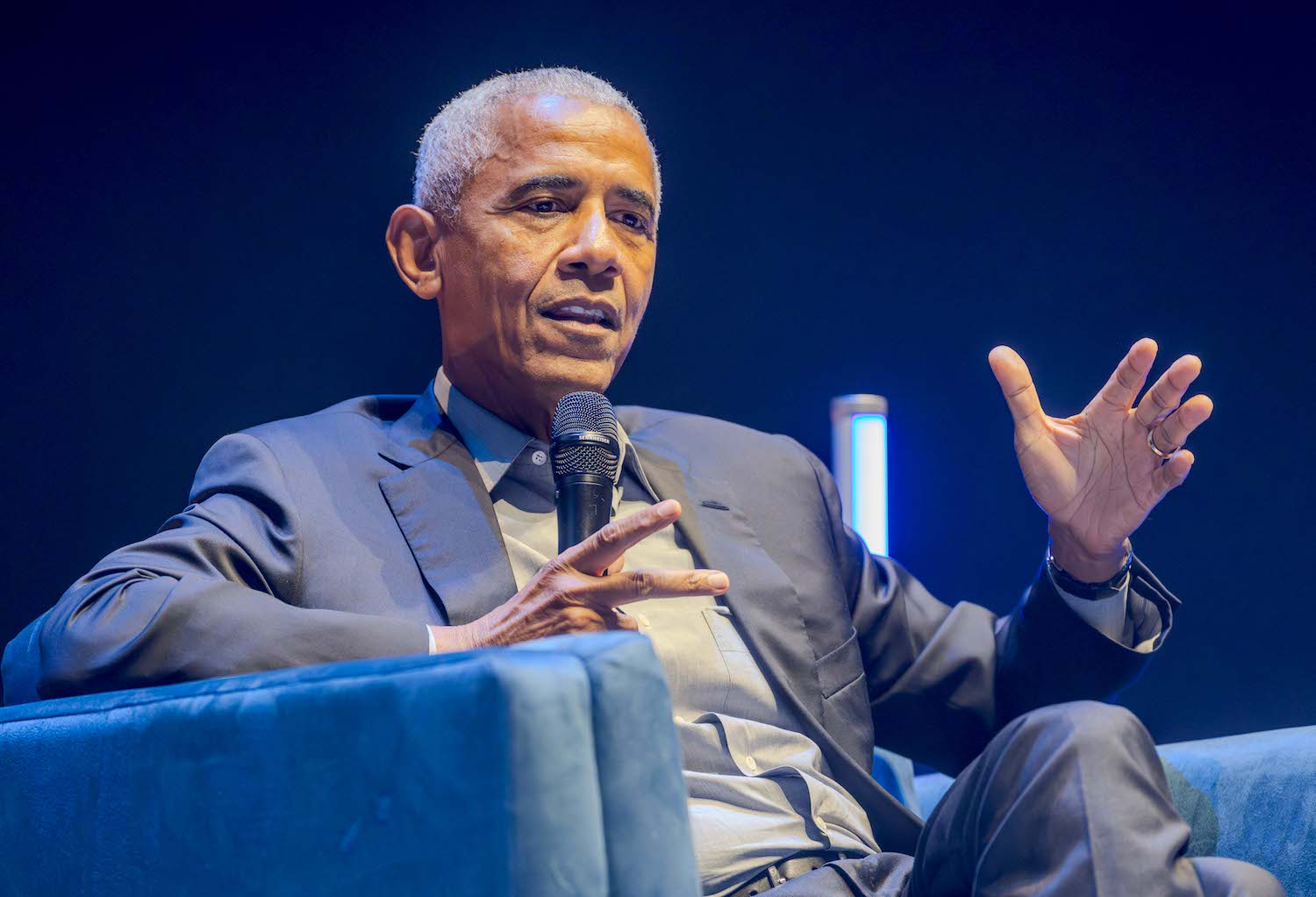

What do the likes of Warren Buffett, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Oprah Winfrey and Russell Brand have in common? They are all fans of neuro-linguistic programming (NLP), a pseudoscientific hodgepodge of strange hacks and corny aphorisms supposed to change an individual’s thoughts and behaviors. NLP practitioners claim to have the power to help clients achieve desired outcomes. Comedian Jimmy Carr, currently touring the US, recently spoke about the power of NLP during an interview with podcaster Chris Williamson. Carr has also spoken about the power of NLP on other hugely popular podcasts.

Like Buffett, Clinton, Obama and Brand, Carr has achieved unimaginable levels of success. But the idea that NLP can help you reach some higher plane of awakening is not rooted in solid science. In fact, it’s not rooted in any science at all.

Many readers, I’m sure, have never heard of NLP. But it has been around for the best part of fifty years. In 1975, Richard Bandler, a self-help guru, and John Grinder, a well-known linguist, wrote The Structure of Magic, a book heavily influenced by Noam Chomsky’s theory of grammar. Although the book comes with some insightful tips, many of the authors’ claims are, at best, laughable. Not only can NLP treat various phobias, readers are told, it can also cure allergies, learning disorders and even the common cold, in just a couple of sessions. Moreover, Chomsky’s theory of language, the very theory that helped inspire NLP, is built on a foundation of sand. From the very beginning, this form of programming was flawed. Today, thanks to the rise of questionable life coaches and even more questionable leadership training programs, it carries very little, if any credibility at all.

Rob Yeung, a chartered psychologist who has discussed the problems with NLP in great detail, tells me that one of the biggest flaws of the practice “is that there is almost no scientific evidence to support its claims. There have been more than ninety separate studies conducted worldwide looking at NLP by reputable academics and psychologists and not one of these investigations has found evidence that NLP works as it is supposed to.”

“Of course,” he adds, “practitioners of NLP believe that they have witnessed meaningful change in themselves and their clients. But for me, that’s like someone saying that their grandfather smoked twenty cigarettes a day and lived till he was ninety years of age despite the vast majority of scientific evidence suggesting that cigarette smoking is incredibly harmful to health.”

He’s right. Anecdotal observations that something works (or doesn’t work) should never be confused with legitimate, scientific evidence.

Yeung advises people to steer clear of NLP, an unregulated practice that often fashions itself as a form of psychotherapy. Instead, he says, focus on “interventions that are supported by scientific evidence such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) or even counseling.”

Wise words. Sadly, though, NLP, which offers a host of quick fixes to complex problems, continues to grow in popularity. This is especially true in the US.

In one study, which Yeung previously referred to, a team of researchers interviewed more than 100 mental health professionals, asking them to rate the credibility of various therapies on a scale of 1 (for “unimpeachable”) to 5 (for “appalling”). The worst rated was angel therapy, a form of spiritual healing that involves soliciting the services of your guardian angel. Not surprisingly, this kooky form of therapy was rated 4.98 out of 5. Another nonsensical form of “therapy” known as past lives therapy was rated at 4.92. NLP, rated at 3.87, didn’t fare too well either. According to the researchers, NLP ranked lower than other questionable therapies used to treat Freud’s concept of penis envy, in which young females experience anxiety when they look down and realize that are not in possession of a penis. Other folks have compared NLP to a pyramid scheme, with current members tasked with bringing in new clients. With its wild claims and die-hard disciples, NLP has a Scientology vibe to it. One group of experts have even compared NLP to a cult.

Edzard Ernst, a retired medical doctor and professional skeptic, has exposed the failings of NLP on more than one occasion. Dr. Ernst tells me that, although NLP practitioners claim to offer a sort of “user-manual for the brain,” the scientific literature analyzing its claims paints a very different picture. Moreover, he adds, “the evidence to suggest that NLP might be effective in treating illness is equally weak. If NLP is used as an alternative to effective therapies, it can do considerable harm.”

Jonathan Passmore, another expert who has done a great deal to shine light on this cult-like practice, agrees with the criticisms of Yeung and Ernst. Like Yeung, Passmore is also a chartered psychologist. And, like Yeung, he also thinks NLP poses far more problems than solutions. As he tells me, too many have bought into and continue to “buy into it like a Madoff scheme.” Passmore is particularly concerned by the fact that NLP has, in his own words, “stolen” a number of practices from more credible practices, like CBT and gestalt therapy, and presented them as its own.

Passmore’s concerns are warranted. That’s because many proponents of NLP are liars. Literally. They regularly claim that they can spot a liar from a mile away. They can’t.

For years, NLP leaders have suggested, rather ludicrously, that it’s incredibly easy to sport a liar. In short, a person who is fibbing will glance up and to the right when you look at them, whereas a truthful person will look up and, to quote Beyonce, to the left. For NLPers, the relationship between eye movement and internal thought is an intimate one. However, as the psychologist Richard Wiseman has shown, when it comes to lie detection, the eyes tell us very little.

In one study carried out by Wiseman and his colleagues, “the eye movements of participants who were lying or telling the truth were coded, but did not match the NLP patterning.” In another study, also carried out by Wiseman and his colleagues, one group of participants learned about the NLP eye-movement hypothesis, and another group (control group) did not. Shortly after, both groups undertook a lie detection test. As Wiseman and the other psychologists noted, no significant differences between the two groups were detected. “Taken together,” they concluded, the results of the studies “fail to support the claims of NLP.” Shocking, right?

Absolutely not. NLP, as mentioned at the very beginning of this piece, emerged from flawed science. In the years since, via a snowball effect, it has accumulated other science-free claims and practices — like manifestation, for example.

NLP is closely associated with the child-like idea of manifestation, a preposterous technique that mixes delusion with entitlement. For the uninitiated, manifestation involves putting a wish out into the universe, and waiting patiently for the universe to respond. In other words, if you want something bad enough, simply think it into existence. I am currently awaiting the delivery of a new Maserati.

NLP, like so many other quasi-religious practices, appears to be filling the void once occupied by genuine religious belief. Hacks, gurus and con artists identified this void many moons ago, and found inventive ways to exploit it. Empty aphorisms and positive self-talk doesn’t come free, with certification courses costing thousands of dollars. Not only do NLPers provide questionable advice, they also train others in the dark art of sharing this questionable advice with other poor suckers. Five decades on from its inception, the cycle remains unbroken.

Of course, it’s possible that NLP has worked wonders for the likes of Warren Buffett, Oprah, Obama and Jimmy Carr. It’s far more likely, though, that these super successful, ridiculously wealthy people discovered NLP when they were already on their respective paths to success. In other words, it’s highly unlikely that NLP was the key ingredient in helping Obama become the forty-fourth president of the US, or helping Oprah become America’s most famous talk show host in history. Did NLP help make Jimmy Carr a funnier comedian? Probably not. Did it help Buffett make better investment decisions? Again, probably not.

That’s because NLP is not rooted in science; it’s rooted in exploitative opportunism. It feeds on the gullibilities of naïve individuals in the US and beyond, many of whom possess myriad, complex problems and are in search of a silver bullet.

It’s easy to see why NLP, rich in clichés, pseudoscientific claims and full blown dishonesty, is so attractive to so many. But take a step back, remove the tinfoil hat and actually acknowledge its failings — and it’s easy to see why NLP is, at best, a load of glorified nonsense.

Leave a Reply