Sandy Hook was supposed to be the tipping point in our national conversation about mass shootings. This wasn’t a shopping mall or movie theater. It wasn’t a high school. We could imagine this happening at a high school. We had seen that before. But we could not imagine anyone shooting six-year-olds. It was so monstrous that it seemed beyond the realm of possibility.

Since that day, 13 years ago, the killings have continued and their settings have shifted. Earlier this month, a gunman opened fire at a Turning Point USA event, fatally shooting conservative commentator Charlie Kirk. In the past year or so, 15-year-old Natalie Rupnow killed a teacher and a fellow student in Madison, Wisconsin, before taking her own life. Solomon Henderson opened fire in a Nashville school cafeteria. Luigi Mangione allegedly murdered healthcare executive Brian Thompson. Aaron Bushnell set himself on fire outside the Israeli Embassy in Washington, DC.

These episodes are not identical. What unites them is an atmosphere: not tidy ideology but an appetite for meaning where meaning has been hollowed out.

Two specters haunt our culture, and both conclude that life should be extinguished. The first says life is meaningless. The second says life is suffering. They arrive at the same destination from different directions. The nihilists believe in the void. For them, all human values are illusions, all meaning is projection, all morality is “cope.” Violence becomes their demonstration: proof that nothing matters.

The Columbine killers left behind hours of video explaining this worldview. James Holmes, the Aurora theater shooter, documented his sense of meaninglessness. William Atchison posted for years about nihilism before killing two students in 2017. Their massacres were philosophical proof that caring about anything was absurd.

Before the internet, killing manifestos would have stayed in evidence lockers. Now they circulate endlessly online

The other philosophy comes from pain, not emptiness. Life is not meaningless but unbearable. Adam Lanza, who committed the Sandy Hook massacre argued that culture itself was a disease and schools were its transmission belt. Killing children, in his philosophy, was a mercy: putting an end to life before it could propagate suffering. He spent years developing an anti-natalist framework explaining why human consciousness itself was the error. This is not nihilism but something else entirely: the conviction that existence is fundamentally malignant. Today’s killers inherit one or both philosophies.

Mangione appears to have absorbed years of discourse about the moral emergency of medical bankruptcy and denial of coverage until the healthcare system seemed so cruel that killing an executive felt like justice. Bushnell consumed footage of the destruction in Gaza until self-immolation seemed the only proportionate response to unbearable reality. It now seems plausible that Tyler Robinson watched political polarization escalate until violence appeared to be a logical act of justice against a hateful world. To these young assassins, the system is torture and spectacular action is the only authentic response. Rupnow and Henderson found their way to “764,” a decentralized online network that grooms young people into self-harm and violence. Such networks are like pneumonia attacking someone who already has HIV. They don’t create nihilistic children; they find the ones who are already hollowed out by the media environment, already convinced they have no future – that the world has no future – already oscillating between numbness and panic. The groups are symptoms more than the disease. They could not recruit effectively in a culture that gave young people genuine hope.

Journalists and politicians still default to familiar explanations – guns, video games, mental illness – because those frames are simple and politically serviceable. The left calls for stricter gun control; the right leans on mental-health narratives. But both of those responses miss the crucial layer: the cultural conditions that make both philosophies persuasive.

Earlier mass killers had comprehensible motives: postal workers had grievances, political assassins had targets, even serial killers had pathologies and fixations. But Columbine, in 1999, introduced killing as philosophy. Before the internet, the manifestos that accompany such actions would have stayed in evidence lockers. Now they circulate endlessly online, providing vocabulary for those who already sense the void or the pain, but lack words for it. Each new shooter studies the last, refining the argument.

The internet doesn’t create these philosophies but accelerates their transmission. This is why policy responses that focus only on guns or only on therapy or only on “rooting out” political extremism will fall short; they are necessary but not sufficient. Shutting down grooming networks treats the pneumonia, not the HIV. We must address the underlying condition: the media environment that oscillates between numbness and panic, the economic system that tells the young they have no future, the culture that produces people primed for violence.

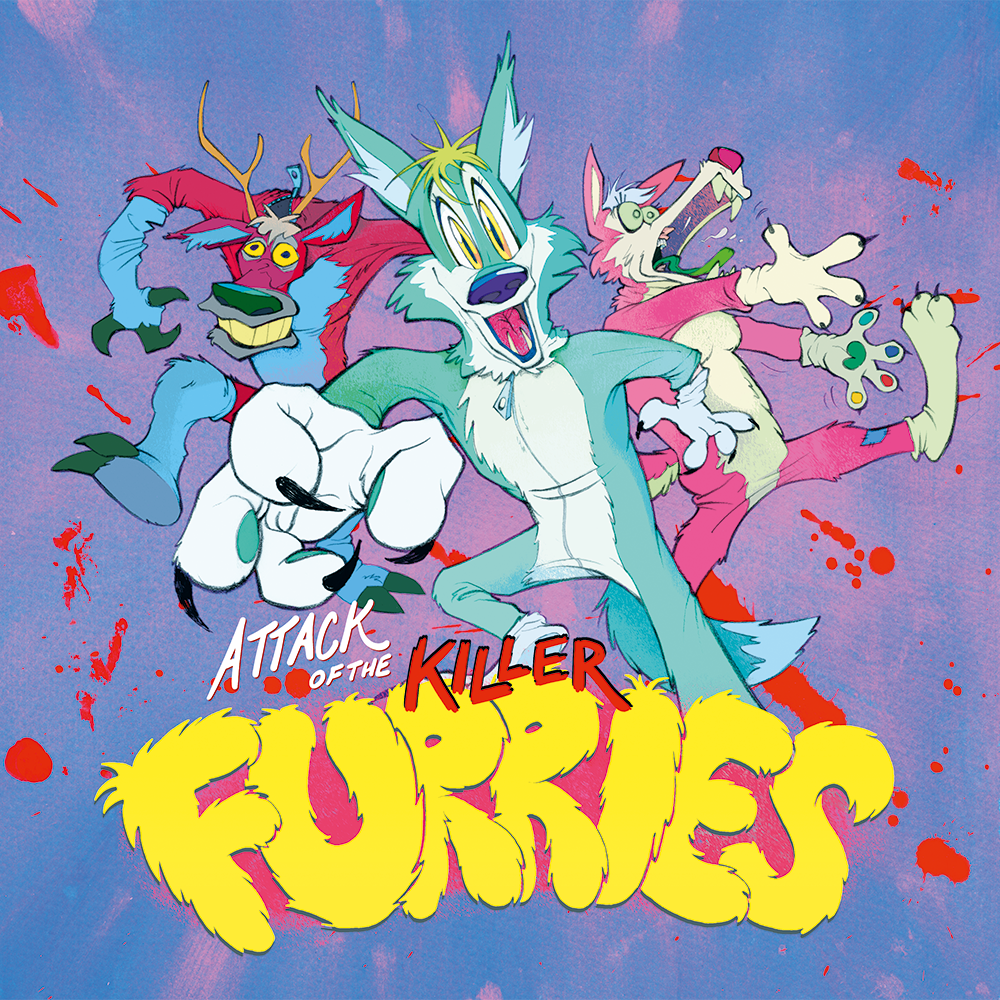

About a year ago, I interviewed a young man who had fallen into one of the darkest corners of the internet via the “furry community.” Furries are people who role-play as, draw fan art of and, famously, wear fursuits of anthropomorphic animals. They’re more important to the history of the internet than they’re often given credit for. They were experimenting with identity in online environments long before most people first logged on to social media. The culture of pseudonymous performance, fan-driven art economies and elaborate online communities – now standard features of the internet – were partially pioneered in furry spaces. Most furries are, at worst, eccentrics immersed in a fandom that doesn’t always feel accessible to normal people.

That being said, there is a fringe dark side to the furry subculture and this boy’s involvement led eventually to him watching violent, animal-torture pornography. There aren’t many practical case studies of what falling down an internet rabbit hole looks like, so his experience and the conversation we had matters. It shows how these online communities can potentially mutate and hurt people, and how some of those offshoots can draw people toward obsession, alienation and harm.

It should be a warning to all parents everywhere that this boy wasn’t a troubled or traumatized kid. His parents were inattentive, not criminally neglectful. “My home life was pretty calm,” he told me. “My parents worked a lot. They’d usually be home at maybe five or six. And from there they wouldn’t really, like, interact with me much. I would just be in my room and I would say I was doing homework when really I wouldn’t even start doing homework until ten.”

In seventh grade the boy got a smartphone and at that point, he says, his internet usage got out of control. He’d be online until two or three o’clock in the morning. His parents did notice his internet addiction but they were out of their depth. “They tried to push me to go to club meetings or they’d set up screen-time passwords,” the boy told me, but younger generations are at home online in a way their parents are not. He says he felt like he was always a step ahead of them. They never saw the extreme, violent pornography that the boy ended up addicted to. “If they did discover anything there, they never said anything, which frankly, if that was the case, I don’t think I could forgive them.”

The furry community can be and often is benign, but as the boy says, it can also be a portal to an actual hell. “It was very easy to find people who are into normal furry stuff, and then find people who are specifically into furry drawings of like realistic genitals, and then hyper realistic stuff. And from that point, it’s very easy to find just straight up zoophilia. I feel molested by the internet – that’s how I’d describe it,” he says. “I feel like it touched me someplace, very deeply, like part of my soul was trapped in cyberspace and I’ve been kind of clawing to get it back.”

Violence has become imaginable to people who before might have found solace in work, family or civic life

I do not want to blame the internet. But the internet is like a sort of fairyland – as full of danger as it is enchantment. What we face in such a moment is less a conventional political battle than a spiritual one. This boy’s experience is a perfect case in point. The choice is not between conservative or progressive policies but between frameworks that affirm life and those that render it either meaningless or unbearable. America’s epidemics of despair have combined with technological access to make violence imaginable to people who, in another era, might have found solace in work, family or steady civic life.

If we are to respond honestly, we must recover the vocabulary of meaning-making: institutions which offer identity beyond consumption and outrage; communities that restore durable ties; media that privileges context over immediacy; and education that teaches people how to live, not just how to perform. This will not be quick. It will not be purely legislative. But until we address what makes both “life is meaningless” and “life is unbearable” persuasive philosophies that demand violent manifestation, we will keep mistaking symptoms for causes.

Until we confront that – until we admit that even ordinary-seeming people can be recruited into these philosophies – we will continue to misdiagnose what happened in these classrooms, cafeterias and political spaces. The specters are everywhere now: in the manifesto and in the feed, in the philosophy seminar and in the TikTok video.

These are not anomalies. They are signals that America’s crisis is not only political or technical but spiritual: the routinization of despair, the auditioning for obliteration.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 29, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply