London

For the past year or so, I’ve been involved in selling The Spectator as well as editing it. A long auction involving moguls, sheikhs and an act of parliament has finally produced a winner. The financier Sir Paul Marshall has become the fourteenth proprietor of this magazine. His faith in our prospects is reflected in the size of the deal: £100 million ($130 million), five times what we were valued at when we split from the Daily Telegraph in 2005. We had twenty-two interested parties, some of the greatest names in British and European publishing, all bidding each other up. The result stands as a spectacular vindication of what my colleagues have achieved. I think it’s safe to say that the death of political and cultural magazines has been somewhat exaggerated.

After the deal was announced, I spent the day speaking to broadcasters who wanted to know if Sir Paul is doing this not because he wants to buy a growing magazine but because he wants an incredibly expensive means of influencing Britain’s Tory leadership contest. Set aside the fact that we don’t endorse candidates. We cover politics well — better than anyone — but to see The Spectator as a political project fundamentally misunderstands its purpose. The latest issue of our UK magazine contains sixty articles, of which only a few are about Westminster politics. Spectator readers expect to be taken “to all parts of the human experience,” as one of my predecessors put it, and “believe that the Bible and Homer are far more interesting and important, sub specie aeternitatis, than the price of oil or Tory prospects.”

I once bought at auction a letter written by the then retired Harold Macmillan turning down the chance to buy The Spectator. It had become too political even for him. It was then owned by a Tory Member of Parliament and had recently been edited by another. The combination was deadly and sales were in freefall. We had almost gone bust when Sir Henry Keswick, a financier, bought us for £100,000. He hired Alexander Chancellor as editor to restore the magazine’s original virtues: independence of opinion, originality of thought and elegance of expression. And robust editorial independence.

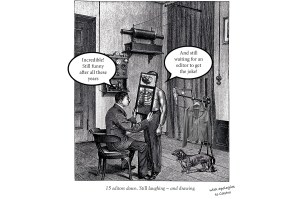

Algy Cluff paid £160,000 for The Spectator in 1980 and wrote to Chancellor with his thoughts on how to improve (more coverage of Asia, etc). “This he printed as a letter, as if it were from a reader!” Cluff recalled. Charles Moore did the same with Conrad Black’s advice. The Barclay family gave me not a single editorial hint or suggestion, let alone instruction, in fifteen years. Andrew Neil, who has just stood down as chairman after twenty years, dealt with them, seeing it as his job to protect our freedom. We used that freedom to quintuple our value. Editorial independence isn’t an optional extra. It’s what makes The Spectator: decades of experience, good and bad, testify to that. As Sir Paul has made clear, it’s a formula he seeks to protect and invest in.

At a live recording of our Coffee House Shots podcast last week, a gloomy reader asked what, if anything, was good or unusual about Britain. The great Alan Clark, when he was asked that same question by a schoolboy, said: “It produces people like you who ask questions like that.” He meant it as a rebuke, but I’m not so sure. Great nations are always self-critical. My immigrant wife puts it well. She says she has moved to the best country on Earth, but one that is weirdly determined never to admit to that. Kemi Badenoch also has what might be called this immigrant patriotism. When she worked at The Spectator as our digital chief, she would berate me for running so many negative articles. In my view we’re effervescent about Britain — and the world, compared with most other publications, but clearly not enough for her. Growing up in Nigeria, she saw Britain as an ideal as well as a nation: a point that would, of course, be lost on natives. I ended up answering the podcast guest by quoting Burns: “O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us / To see oursels as ithers see us!”

Last week, I was delighted to find a note asking me to call Sir Henry (now eighty-five). I wanted to tell him how much the magazine he saved is now going for. “I know,” he replied. “And if the new proprietor asks, I’ll recommend that he fires you.” Crestfallen, I asked why. He said we refused to review a book by Tessa, his late wife, about her time in China. I told him that my colleague Cindy Yu loved the book and had at the time of its publication recorded an interview with Tessa for her podcast Chinese Whispers — a permanent record of the wit and warmth of this wonderful woman. Sir Henry hadn’t been aware. We’re on good terms now. I’m delighted — without him, our magazine’s story would have ended fifty years ago. As things stand, its best chapter may very well be about to begin.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply