One of the first pieces exhibited in Superfine: Tailoring Black Style – The Met’s annual spring Costume Institute exhibition – is a small and faded tan wool livery coat, most likely created by Brooks Brothers, the oldest apparel brand in continuous operation in the States.

On its website the New York-based Brooks Brothers proudly claims that since it was founded in 1818 it has dressed no less than “39 presidents, along with industry leaders and cultural innovators.” What it doesn’t say it that it also dressed southern slaves.

The mid-19th century tan coat was worn by a black enslaved child, just before the Civil War, at a time when household servants reflected their owner’s status. While it is more subdued than some of the other outlandish outfits slaves were dressed in displayed here (sometimes matched with ornate turbans, a nod to their “exoticism”), the coat does feature prominent large metal buttons. The buttons are stamped with falcons, an emblem of plantation operator Dr William Newton Mercer, whose crest was as a symbol of ownership.

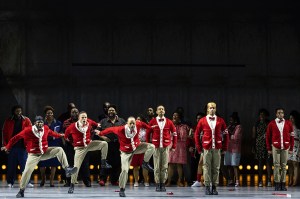

Superfine, curated by Monica L. Miller, a professor of Africana Studies at Barnard, alongside the Costume Institute’s Andrew Bolton, is as much a thesis as a clothes exhibition, and as such is imbued with a depth not usually found in such exhibitions. Featuring three centuries of garments, but also paintings, cartoons, photographs and documents, it is inspired by Miller’s book Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diaspora Identity.

Miller posits that dandyism – dressing in a foppish, overtly modish manner – was imposed on enslaved black men in the 18th century by their owners, who treated them as a “luxury” item to show off their wealth. When able to reclaim their liberty, black men used dandyism as a political and sartorial tool to project their own identities and personalities on the world. Clothes were more than fashion: they were about urgent agency and autonomy.

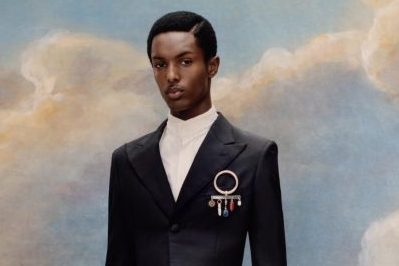

As in all the Met’s Costume Institute exhibitions, there are dozens of showstopping pieces here, this time by black designers, from Pharrell Williams to Virgil Abloh. But the devil is in the details. Superfine is at its most impactful not for its razzle dazzle but for the smaller items on display and for the text that accompanies them: there is a wealth of historical information here, in equal measure horrifying and inspiring.

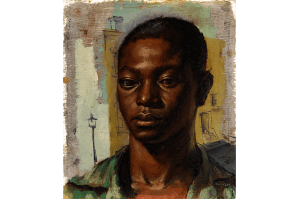

The horrifying includes French 17th-century fashion plates that pictured women dressed in the latest styles alongside black servants in whimsical livery. The idea was not only that the men were an extension of a lady’s fashion, but that their dark skin made her fair skin look better. “Beauties whose only intention/ Is that everywhere you are adored/ To raise the radiance of the complexion/ Like me, Use a Moor,” reads a ditty below one plate.

Superfine soon moves to reclamation and defiance. The exhibit takes its name from a 1789 autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. Equiano, who was kidnapped as a child and sold into slavery before purchasing his own freedom and becoming a vocal abolitionist in London, used his good sense of dress as a weapon to project his innate worth. Equiano understood that clothes communicate power, status, hierarchy (or lack thereof). As he recalls: “I laid out above eight pounds of my money for a suit of superfine clothes to dance with at my freedom.”

Moving into the modern day, the designers on show riff on that idea, some with breathtaking success. Take the British Jamaican menswear designer Grace Wales Bonner whose fawn-coloured silk crushed velvet jacket and trousers, tucked away in a corner, literally made me gasp. Embroidered with tiny milk-colored cowrie shells, crystals and glass pearls and paired with a bold gold-plated brass headpiece adorned with glittering Swarovski crystals, the ensemble is both gorgeously tactile and somehow winningly un-presuming.

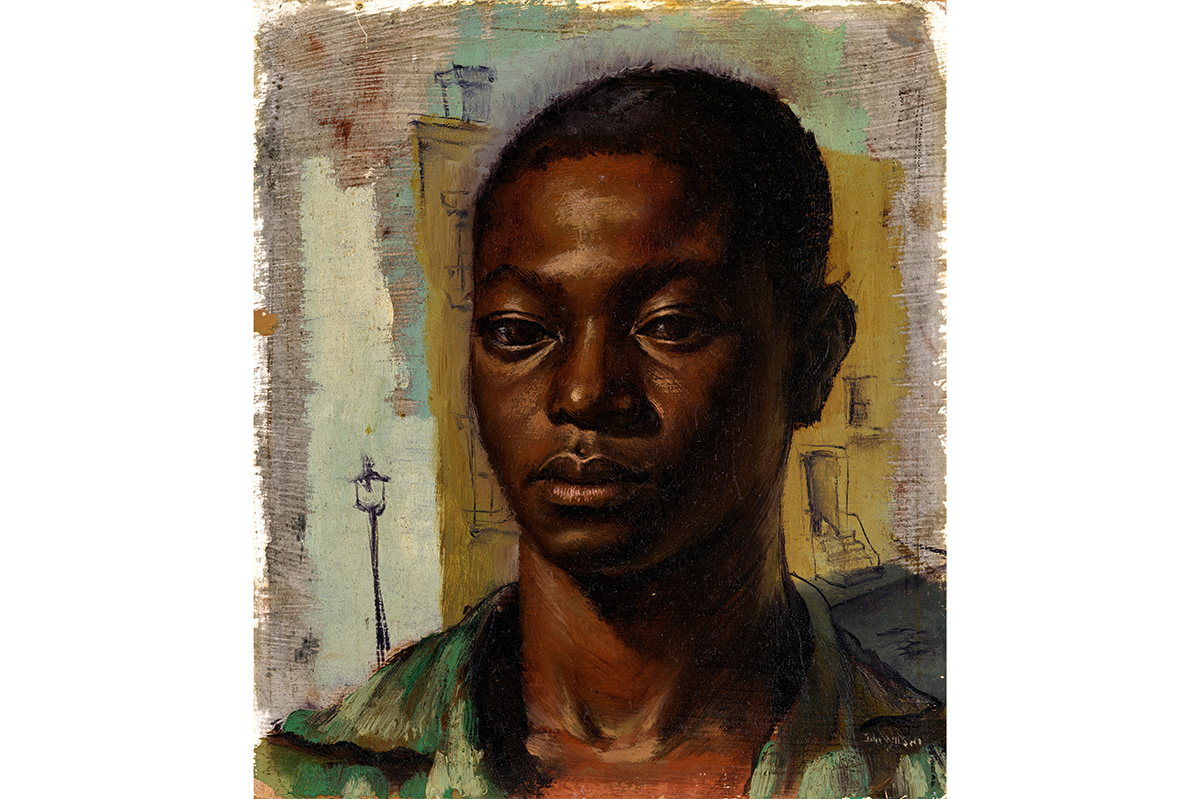

Bonner was inspired by the black men who were exoticized in European portraiture. Yet she simultaneously reclaims a sense of power and self-ownership by including the cowrie shells, used as currency in Africa and the West Indies, which represent a form of indigenous riches and affluence that are independent from the white man.

That Bonner can today be so playful is in no short order due to the pioneers that went before her. And in that comes Superfine’s most powerful message. One of the more moving documents is a small photograph of the sociologist William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, who became the first black man to earn a doctorate from Harvard in 1895.

The 1900 image shows a dapper Du Bois in Paris dressed in a gleaming top hat and a sharply tailored morning suit. His chin is ever so slightly lifted, denoting confidence and a strong sense of his place in the world; his hands are casually thrust into his pockets. He is the definition of a handsome, debonair, well-dressed, well-travelled man, in control and at ease. This was someone who was writing his own narrative, of his dress as well as his life.

In 1925, as the caption tells us, he ordered two extra suits. A small act, of course, that might be missed except for the shift the instruction denoted. They were from Brooks Brothers.

Leave a Reply