This is a short piece on Holocaust Memorial Day, and what it means to be descended from Holocaust survivors. Many, many people could write a story like this, but this one is mine.

All parts of my family lost people in the war. My grandfather, though, lost pretty much his whole family. They were in Krakow, in Poland, and only he and one brother survived. His first wife, his baby daughter, his parents, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews all died.

To understand the immediacy, that’s my mother’s half-sister, grandparents, her whole extended family. All gone before she was even born.

Recently, I’ve been trying to find out about them. It’s really hard. My grandpa died when I was three, and I gather he didn’t like to talk about the past much. So, now, there are only really two sources.

One is a record of births, marriages and deaths from Krakow, but it’s pretty muddy. The other is the testimonies of the dead left to the Holocaust museum at Yad Vashem by my great uncle, my grandpa’s brother, who fled to Brazil after the war.

That’s priceless, but fairly muddy, too. Particularly vexing is the lack of mention of my grandpa’s first wife and daughter, probably because they died at the hands of Russians, not Germans. We’re not even certain of their names. To repeat, that’s my aunt. No names.

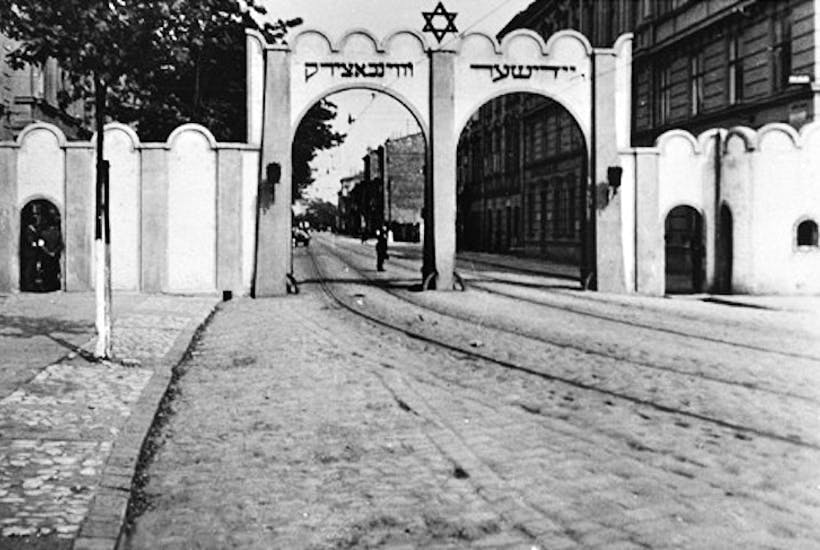

The one I fixate on is Ryszard, the child of my mother’s uncle. He died aged nine. That’s the age of my own eldest kid. The ‘circumstances of death’ box for Ryszard says ‘Actions against children in Podgorze Ghetto’. I think about him a lot. It seems very important to remember him.

I don’t know who his mother was, though. On the testimony form, the name of his mother doesn’t match other records for the uncle’s wife. I don’t know if this is a mistake, or if she had two names, or if he had two wives. I have nobody to ask.

It’s possible his father wasn’t even who I think he was, but another close relative with the same name. I don’t know. Which means nobody knows. Because there is nobody left who might. Nor was there even anybody left who might have told somebody else.

Now, obviously these are the travails of any historian or amateur genealogist. I get that. But this is not ancient history. When these people died, my own, normal, London terraced house had already been standing for 50 years. Many of them would still be alive.

Even if they weren’t alive, they would be remembered, photographed, known about. They aren’t. The point being, it wasn’t a failure, the Holocaust. It wasn’t curtailed. It was a plan, carried out, which worked very well.

These people are gone, eradicated, flushed down the memory hole. Reduced, at best, to scraps and half-remembered fragments. In the space of a lifetime. So, you remember what you can, and as loudly as you can.

Because otherwise, there is nothing left at all.

This article was written for Holocaust Memorial Day on January 27 and was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website. Please consider visiting the Holocaust Educational Trust for more information.