Why does the United States seem to be falling apart? The ideal that used to bring Americans together seems to have failed in some way. “Liberty and justice for all” is the best summary. Sure, it was always a frail creed, and interpretations of it differed, but still. It semi-worked.

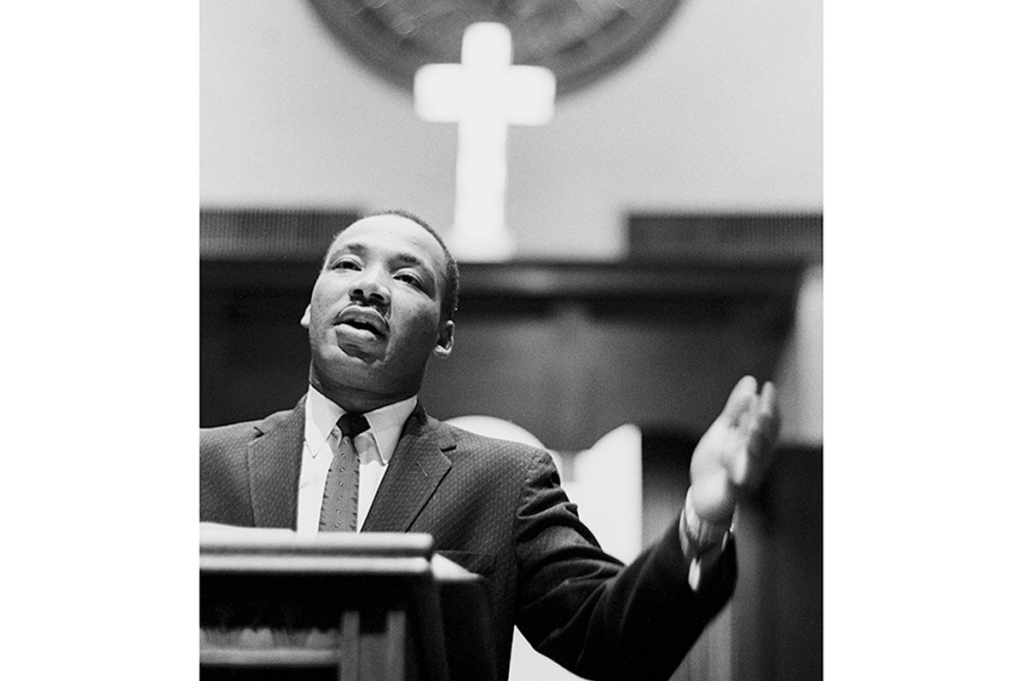

The creed failed in a very paradoxical way. It was voiced too well, too purely. Its greatest articulator was Dr Martin Luther King, who is commemorated with a US national holiday celebrated on Monday. (Ronald Reagan signed Martin Luther King Day into law in 1983, in less sectarian times.)

The problem, of course, was that Dr. King was black. Half of white America found this hard to take: that the incarnation of the national ideal did not look like them. But another aspect of his identity also served to alienate about half of Americans: King was a liberal Protestant Christian. He was — above all else — a clergyman, like his father, grandfather and great-grandfather before him.

“All that I do in civil rights, I do because I consider it part of my ministry,” he said. “I have no other ambitions in life but to achieve excellence in the Christian ministry. I don’t plan to run for any political office. I don’t plan to do anything but remain a preacher.’

To remember King while ignoring his faith is not to remember King at all. Yet today he is often venerated by those who have very little interest in his Protestant Christian message. His repeated emphasis on forgiveness and loving enemies is not the spirit that animates today’s statue-topplers.

Why was King’s liberal Protestantism such a crucial underpinning of the American ideal? Because it was capable, just about, of holding together religious conservatives (those famous tall-hatted Calvinists and their heirs) and the rest. It’s America’s glue. Or was, for it seems to have dried up.

King stumbled into politics during his first real job, as a young Baptist minister in Montgomery, Alabama. When Rosa Parks’s bus boycott took off, it needed an organizer. Emmett Till had been lynched in Mississippi a few months earlier, so violent retaliation seemed on the cards. But King began to see himself as a peacemaker, on a national scale. In 1957 he founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with the slogan “To save the soul of America.” In fact, its target was global, for he linked his work to the decolonization under way in Africa. At Ghana’s independence ceremony he prayed that “it will come in this generation: the day when all men will recognize the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man.”

This fusion of the Bible and humanism was the staple of liberal theological colleges, including Boston University where he had studied. The mood was influenced by exiles from the Nazis such as Paul Tillich, and also by Protestant missionaries who had become passionate advocates of racial equality and were open to ideas from other faiths, including Gandhi’s non-violent protest. More moderate liberal Christians were reassured by the avuncular presence of Reinhold Niebuhr, arch-advocate of Christianity’s compatibility with liberal democracy. In short, liberal Protestantism was in a bold expansive phase.

In the early 1960s, King’s rhetoric became more focused on the spiritual identity of America. In his famous Washington speech, he went straight for the spiritual jugular. “When the architects of our great republic wrote the magnificent words of the constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” And he returned to the theme in the peroration: “I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed. We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal.”

No white person could have revived that founding rhetoric with such force. He understood that such rhetoric belonged more to blacks than to whites in a sense, for whites had lost the right to say it sincerely. This was not a new insight: the black campaigner W.E.B. Du Bois had said decades earlier: “There are today no truer exponents of the pure human spirit of the Declaration of Independence than the American Negroes.” But King did not just grasp the point; he performed it on television.

On one level, that speech was an effective bit of campaigning for further racial equality. On another it was a prophetic sermon, imbued with Christian utopianism. But the religious element refuses to stay in a box: King insists that this outlandish vision is at the heart of the nation’s politics. This is who we are, if “we” is to mean anything. But can a nation cope with such an ethos? Maybe it is too demandingly Christian, or Christian-humanist. Maybe its rejection of tribalism is unrealistic, at odds with human nature.

Similarly, can an oppressed minority cope with the role King announced for it? His policy of non-violence, which he always explained as the Bible’s mission, blurs with a sort of cult of holy suffering. Not many people want to hear that their political duty is to suffer violence and never retaliate. King would quote Abraham Lincoln by asking “Do I not destroy my enemies when I make them my friends?” and tell white racists that “We will match your capacity to inflict suffering with our capacity to endure suffering… send your hooded perpetrators of violence into our community at the midnight hour and beat us and leave us half dead and we will still love you.” The black power backlash was little surprise. Historical struggles for justice had seldom been peaceful – why should this one be expected to be meek and mild?

Because, said King, the only route to true peace is through non-violence, and forgiveness. Loving your enemies, he said, is the hard part of the Bible.

MLK Day is a predictable cause for online spats, with woke and anti-woke factions angrily denouncing the other side for daring to recruit the man. They seem to prefer such denunciation to actually trying to reflect on what he said and did. There isn’t much enemy-loving going on in either side.

We are all separated from King’s vision by an immense gulf. His vision was rooted in a particular religious culture, and it collapsed fairly dramatically in the decades after his death. The “mainline” churches emptied fast. This was partly a matter of whites deciding that Christianity (as King presented it) was just too demanding, and too threatening to their idea of themselves. The liberal vision seemed more persuasive in secular form, shorn of the biblical stuff.

I admit that the demise of liberal Protestant theology sounds like rather a niche concern, but it may well lie at the heart of America’s deepening ideological troubles.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.