It was meant to be a crushing defeat ending twenty-five years of socialist rule, and the presidency of a man many see as largely responsible for Venezuela’s economic woes, a humanitarian crisis and rampant corruption. But for many Venezuelans, the only thing crushed following Sunday’s presidential election was hope.

Many of those who are desperate for change say they’ll take to the streets

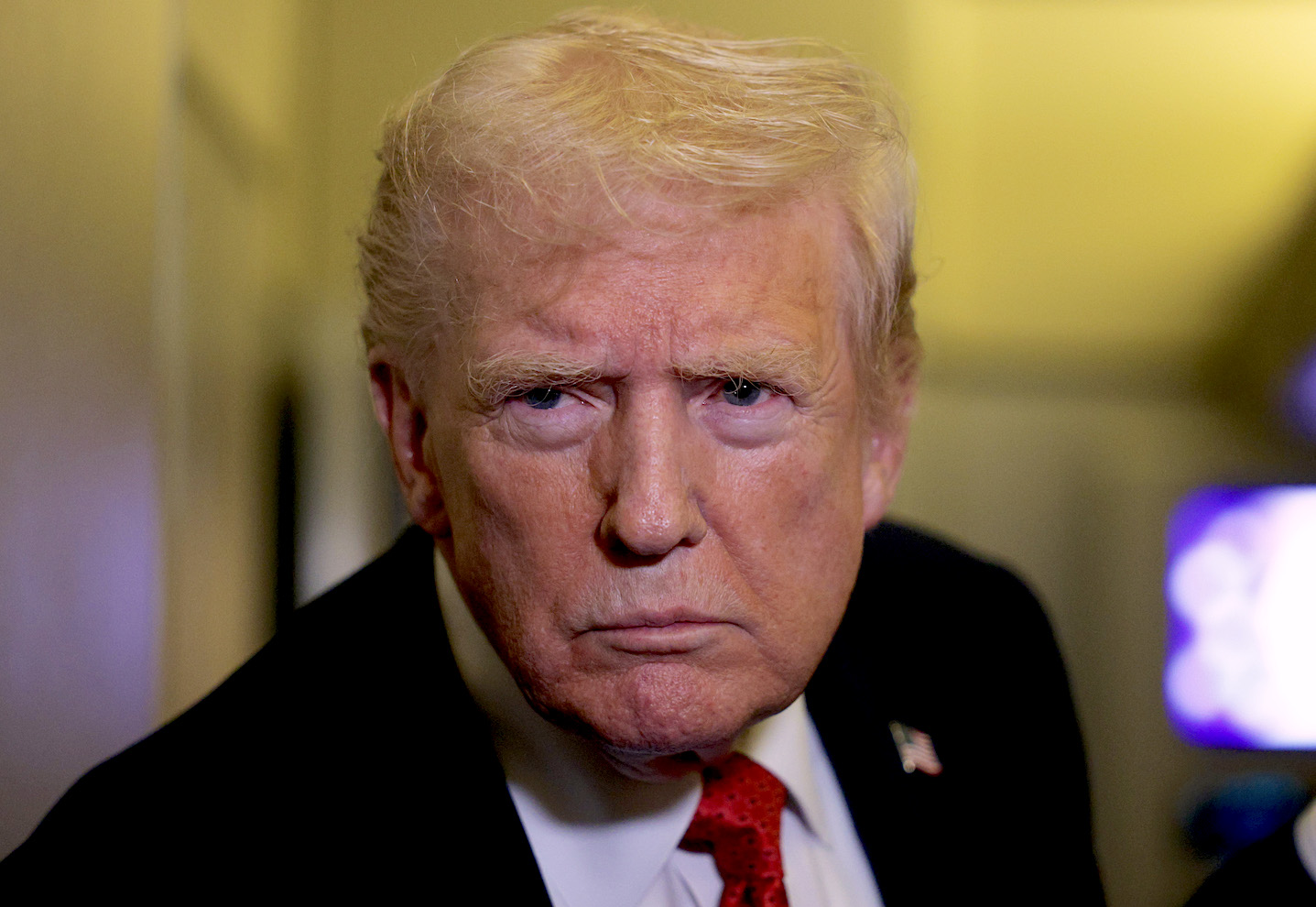

A few hours after polls closed — and amid complaints of some observers monitoring the process being thrown out of polling stations or prevented from entering — the country’s National Electoral Council announced Nicolás Maduro as the winner with 51 percent of the vote; in second place, candidate Edmundo González on 44 percent. “The results are a triumph of peace and stability,” Maduro jubilantly affirmed, teasing the opposition, who he said always cries “fraud.”

And cry fraud, they have. So too have some international leaders, such as those in Argentina and Peru, others expressing “concern” at what appear to be dubious results. Opinion polls in the lead up to the vote showed Maduro trailing lethargically behind González. But the opposition never really expected the government to relinquish power quite so readily anyway. Maduro’s announcement was a surprise to, well, almost no one. The hurdles had been high, and even getting to election day felt an achievement for those calling for a change of government and the chance for a better future.

The leader of the main opposition bloc, María Corina Machado, had been blocked from running — subsequently backing González to stand in her place. Opposition campaigns across the country were marred by roadblocks, detentions of campaign members, including her security chief, and even the closing down of hotels and restaurants who hosted the González-Machado duo.

But high turnout on election day — and a claim by the opposition that González had 70 percent of the vote so far, led to Machado making a bold statement: “Venezuela has a new president-elect and it’s Edmundo González.”

So, on an unusually cloudy and drizzly day in the capital Caracas, Venezuela seems to have two presidents, in sort: one who has the backing of the National Electoral Council, which happens to be headed by a friend of Maduro; and the other arguably having the support of the majority of the population, if figures given by the opposition are to be believed.

Bizarrely, it’s not the first time Venezuela has had two presidents. In 2019, a number of nations, including the US, UK and Brazil, backed the interim presidency of Juan Guaido, leader of the country’s main opposition coalition, in a bid to oust Maduro from power, following what were perceived as fraudulent electrons that much of the opposition boycotted.

It’s also not the first time Maduro has been marred in allegations of foul play. Following the death of his predecessor, Hugo Chavez, in 2013 from cancer, Maduro narrowly clinched victory over presidential candidate Henrique Capriles — an election many claimed was fraudulent. In December, the socialist regime held a referendum on disputed territory in neighboring Guyana. Despite almost empty voting centers, they claimed turnout was ten million. The proof was never released.

The question everyone is scrambling to find an answer to is, “what now?” For Maduro and his allies, it’s likely to be much of the same. During campaign events, where Maduro has sung, danced salsa, and shot basketball hoops, he reiterated countless times that the results would be irreversible.

The government’s tentacles spread widely and deeply into every layer of society, including state institutions and state-owned entities, like the petroleum company PDVSA — and, perhaps most crucially, the armed forces. Dissent, such as anti-government protests in 2014 and 2017, have worrying consequences, including death.

So for the government, and those it controls, the immediate next step will probably be “business as usual.” More strong words against “fascist” and US-backed opposition forces are to be expected, and probably the detention of even more politicians, human rights campaigners and journalists. Perhaps there’ll be a few more of Maduro’s TikTok and Instagram videos too. He’s amassed quite a following in recent months and upped his efforts to appeal to a younger demographic.

As for the opposition, they’re downcast. However, it’s doubtful they’ll walk away so easily. “We won and everyone knows it,” Machado affirmed. “We won’t rest until the will of the people is respected,” González added. Their eyes and hopes will be on support from more of the international community, and perhaps the slim, but still slightly possible, support of the country’s armed forces in backing González as the country’s president-elect .

Machado has been hailed as Venezuela’s’ “last hope” by many of her supporters, a “warrior” who has persevered for years to rid the country of its authoritarian ruler and dismantle the socialist structures in the country first implemented by Chávez, and continued by Maduro.

Machado even has the backing of former chavistas and faithful followers of the Bolivarian revolution, a movement started by Chávez, characterized by a state-led economy and wealth redistribution and patriotic ideals. Many former government supporters have abandoned Maduro, largely blaming him for presiding over a socioeconomic oblivion, caused by mismanagement and corruption, that pushed some to the brink of starvation and a quarter of the population — 7.7 million — people to leave the country. The government blames international sanctions for low salaries, as well as poor public services and infrastructure.

Many of those who are desperate for change say they’ll take to the streets. Machado herself called on people to head to voting centres, a way of demonstrating discontent. But the scars of violent protests in 2014 and 2017 that resulted in a number of deaths, remain etched firmly and painfully into the memories of Venezuelans on all sides. Most citizens say they just want peace.

Others are already planning on migrating if there’s not a change of government, joining family members in other South American countries, or in Spain or the US.

Meanwhile, Maduro supporters are celebrating their supposed victory, satisfied and relieved that for now at least, their revolution — their government and their leader, live on.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply