I’m sitting in a meditation class at a yoga studio in Chicago, neon lights pulsing pink and purple while the instructor talks over a movie soundtrack. I almost can’t believe I’ve paid $30 to be here.

It’s Philip Glass’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, by the way – the score to the 1985 film; it’s become the go-to soundtrack for big feelings and personal epiphanies. The instructor hasn’t stopped talking since we sat down. When she runs out of scripted wisdom about mindfulness and presence, she starts ad-libbing: “and that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t respect yourself…” Her voice layers over Glass’s dramatic strings. I try to tune her out, focus on my breath, but it’s impossible. She demands our attention. I went to six classes before I decided it was a waste of time. Each week, fewer people showed up. By the sixth class, it was just me and this forty-something instructor. Isn’t meditation supposed to train attention through silence and stillness?

This class was a particular failure, but even “successful” meditation has become something perverse in American culture. I believe there are people who have genuinely mastered the practice – or are at least trying in good faith – but for most of us, it’s been transformed into little more than another hobby, another app, another 15 credits spent on ClassPass.

Headspace, Calm, Ten Percent Happier – I download them all, chasing metrics for my mindfulness. But it’s not even about “mindfulness,” per se. It’s about recapturing something that used to happen naturally – the drift before sleep, the empty minutes waiting in line, the quiet moments in the bathroom. All of this has been packaged and sold back to us as a product. We are purchasing temporary relief from a world that never stops asking us something, if not asking something of us.

There’s a scene in The Shining that haunts me. Jack Torrance, trying to write his novel, explodes when his wife interrupts him: “Every time you come in here and interrupt me, you’re breaking my concentration. You’re distracting me. And it will then take me time to get back to where I was.” The scene has become a period piece. Now, we’re never deep enough in thought to be pulled out of it. The “flow state” – that mental zone where hours pass as if they were minutes – has become so rare it requires special workshops.

I grew up rehearsing for this absence of silence. My childhood home, like tens of millions of others, had the television on constantly. Morning shows bleeding into soap operas bleeding into evening news, an endless loop of ambient noise. We complain now about people who watch TikToks without headphones, but we’ve forgotten that some semblance of this was standard practice for decades. The TV was America’s heartbeat, creating a permanent state of half-attention. It trained us never to fully focus on anything.

The absence of silence breeds the absence of thought

In the 1990s and early 2000s, not having a TV became a badge of cultural sophistication. Parents bragged about having children who didn’t even watch PBS, who read books instead. But that distinction was erased overnight with the iPhone’s arrival in 2007. The screen wasn’t confined to the living room – it was in our pockets, our bedrooms, our every waking moment.

My point isn’t about boredom. People are constantly bored. Bored while scrolling Instagram, bored while binge-watching Netflix, bored during conversations. This is about something deeper. The absence of silence breeds the absence of thought. A mind kept in constant stimulation never develops the muscle for thinking. We become capable only of reaction. I like this, I don’t like that. Swipe left, swipe right. But the deeper cognitive work – synthesis, imagination – requires the sustained quiet we’ve all but eliminated from our lives.

Marcus Raichle, a neuroscientist, discovered earlier this century that our brains have a “default mode” that kicks in when we’re not actively focused on tasks. This network, as later research revealed, is where memory is sorted, emotions are processed and our sense of self is constructed. It’s not idle time; it’s maintenance. But we’ve become uncomfortable with our own interiority. In one study, participants chose to give themselves electric shocks rather than sit alone with their thoughts for 15 minutes.

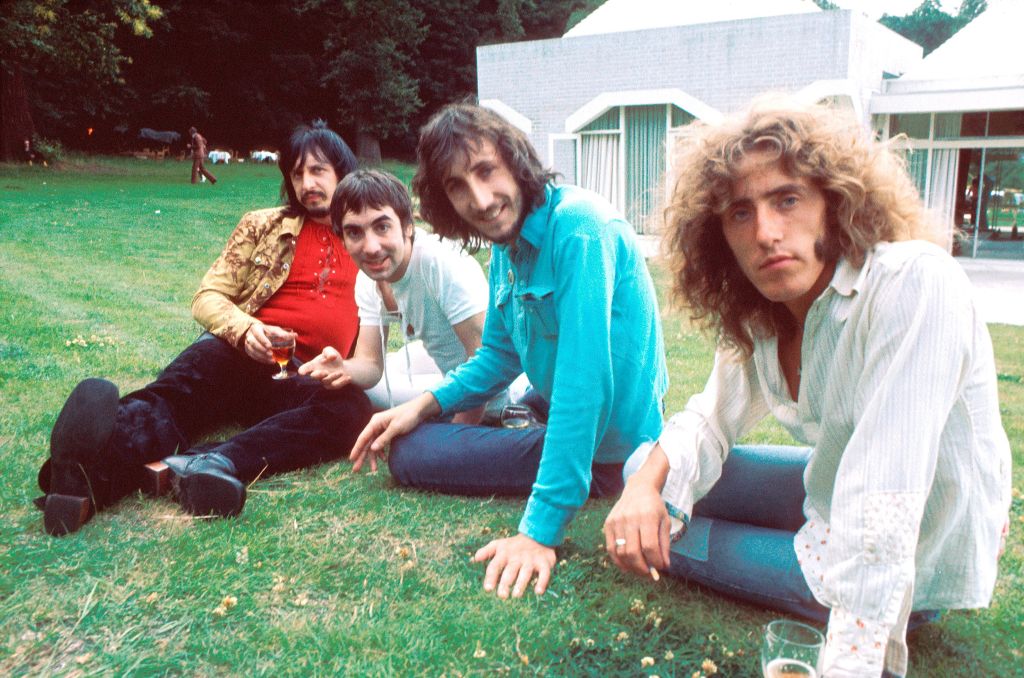

Music has withered in this environment. We’ve gone from sitting and listening to albums – experiencing them as complete artistic statements – to using songs as wallpaper. Walk through Chicago, New York, any American city, and count. Everyone is sealed in their AirPod cocoons, soundtracking their lives. We’ve eliminated not just silence but serendipity: no overheard conversations that change our day, no street musicians that stop us in our tracks, no unexpected connections with strangers.

My ex always maintained a strict no-phones-in-bed policy. When we split, my first act of defiance was allowing my phone into the bedroom. Liberation, I thought. But something was lost. In that darkness before sleep, my mind used to unspool. I’d invent stories, have imaginary conversations, build entire worlds from nothing but silence and time. Now I scroll until exhaustion takes over, falling asleep mid-video.

In silence, we meet ourselves – and we don’t always like what we find. All the questions we’ve been avoiding surface in our consciousness: Am I living the life I want? Am I the person I should be? The silence doesn’t feel empty; it’s too full. So we reach for our phones.

But sometimes you like what you find in quiet. Once you push past the initial discomfort, your mind starts doing things you forgot it could. Strange images drift in – not to-do lists, but actual imagination. A conversation you might have. A scene from nowhere. The kind of weird, associative leaps that used to happen naturally before we filled every pause with content.

Your brain, it turns out, is not such a scary place after all. It just needs space to perform. Without being faced with a constant feed of other people’s thoughts, your own become more vivid, more surprising. You start having ideas: not reactions, but thoughts that emerge from the strange, private cinema in your head.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply