Last summer, US Army soldier Travis King ran across the Korean Demilitarized Zone into the arms of the North Koreans. It wasn’t because of some mental break or as part of a spy operation. North Korean state media claims he was motivated by racism and mistreatment — of course they would. The DPRK’s outlets have previously criticized the US for its treatment of African Americans, around the same time they compared former president Barack Obama to a “wicked black monkey.”

Like the six American servicemen who crossed the DMZ before him, King probably had a mixture of reasons for his flight. Unlike in the previous cases, however, King’s detention was a short one. Those before him spent years or even decades in North Korea with the expectation that they would be permanent prisoners, but King’s usefulness as a propaganda tool — demonstrating the superiority of communist DPRK society over the capitalist evils of America and its western allies — was apparently outweighed by being a troublesome house guest. He was kicked out after just three months, and has returned to the States, where he faces a number of charges for crimes he is alleged to have committed while stationed in South Korea.

Even so, this briefest defector may be the luckiest.

The earliest recorded instance of an American’s willingly defecting to North Korea is Anna Wallis, who later became a Tokyo Rose-like radio propagandist. A Methodist missionary who traveled to Asia, Wallis found herself on the Korean Peninsula when it was still under Japanese colonial control in the 1930s. The Japanese soon cracked down on Christian proselytizing, which led her to relocate to China.

There she met a Korean man named Suh Kyoon-chul; they married in 1939. It was an unusual union — at the time it was highly uncommon for Caucasian women to marry East Asian men — and deeply consequential. US law regarding international marriage meant she lost her American citizenship. Unable to secure an American passport for Suh, the couple found themselves trapped in the chaotic wartime politics of East Asia. Despite being considered a Japanese national (as all Korean citizens were at the time), Wallis was imprisoned with other westerners in a Shanghai civilian internment camp for the duration of World War Two. She resumed teaching following the war’s conclusion but relocated to Seoul with her husband to earn a better living. Suh was an avowed leftist, and Wallis expressed sympathy with his views. As a result, both pledged their loyalty to the North Korean communists after Kim Il-sung’s forces invaded South Korea and temporarily took the capital in 1950.

Now firmly on the side of North Korea, Wallis appeared to be willingly assisting the communists with their radio propaganda. She conducted her broadcasts in a monotone, reporting on captured American POWs or taunting UN soldiers to break their morale. Her listeners dubbed her “Seoul City Sue,” but it’s still unclear whether she was forced to broadcast or was a committed communist. Regardless, these radio programs had little effect on the outcome of the Korean War, which halted when an armistice was signed in 1953.

Following the ceasefire, all prisoners of war on both sides were given the opportunity to choose whether to go home or remain. Only twenty-one Americans and one Briton chose to stay with the communists, while thousands of Chinese and North Korean soldiers decided that life south of the DMZ was preferable. The twenty-two defectors did not actually go to North Korea, however, and instead were given new lives in China. The vast majority ultimately ended up returning home after growing disillusioned with communism, though two, James Veneris and John Dunn, remained in the Eastern Bloc for the rest of their lives.

The next wave of defections to North Korea occurred in the 1960s when the Cold War was in full swing and the ideological lines in the sand were firmly drawn. This era marked a series of heightened tensions and skirmishes along the DMZ between North and South Korea, with thousands of American soldiers stationed as a permanent garrison to defend the south. Unlike the cases of Seoul City Sue and the Korean War POWs, however, the handful of Americans who chose to go to North Korea clearly did not do so for ideological reasons.

On May 28, 1962, nineteen-year-old Private First Class Larry Abshier slipped away from his post and crossed into North Korea. DPRK state media claimed two weeks later that Abshier had made his decision because he could no longer tolerate his “humiliating life” in the US military. The truth was far simpler. According to those who knew him, the private was a regular smoker of marijuana and faced a court-martial for repeated disciplinary problems.

James Joseph Dresnok followed his lead just a few months later, on August 15, running across the border in the middle of the day and ignoring calls to turn back. Like Abshier, Dresnok faced a court-martial for disobeying orders. He regularly forged signatures to leave his station and visit a Korean girlfriend at a nearby village. Jerry Wayne Parrish became the third American soldier defector on December 6, 1963, but his motivations have never been clear. Charles Robert Jenkins, who was older than the other men and a sergeant, defected on January 5, 1965, after abandoning a late-night patrol he oversaw. He would later claim he was making sure he wasn’t sent to Vietnam.

All four men came from extremely poor rural backgrounds; most had had difficult early lives. They seem to have viewed enlistment as the only way to have a better life, rather than subscribing to high-minded, Hollywood-movie patriotism. Similarly, it wasn’t glorious communist ideology that brought them to the “hermit kingdom”; it was legal trouble and cowardice. They probably didn’t know much about their new home, other than it was “the enemy.” None professed any allegiance to communism, and given their lack of formal education, it’s questionable whether they had much political thought anyway.

The North Koreans, however, had a propaganda gold mine on their hands. While it quickly became clear that the four soldiers had little useful intel to divulge, they could still be used to promote the Kim regime’s communist ideology against the American imperialists. DPRK state media attempted to pitch reports of Abshier, Dresnok, Parrish and Jenkins enjoying their new lives in Kim Il-sung’s paradise, having renounced capitalism and the West forever. Even if these statements did little to convince anyone on the outside, four defections in a relatively short amount of time were a profound embarrassment for the US Army.

But life for the four Americans in the DPRK was a different story. In 1966, the group attempted to broker an escape via the Chinese and Soviet embassies in Pyongyang, only to be quickly turned away and apprehended by the authorities. Propaganda appearances immediately ceased and the North Koreans subjected the men to constant study of the country’s ideology, forcing them to phonetically memorize Korean propaganda slogans before they even learned the language. While they had a quality of life far better than the average North Korean, living conditions were even worse than what they had grown up with in poverty-stricken rural America.

The Kim regime chose to award the defectors DPRK citizenship in 1972, believing that their ideological education was complete. In his memoir The Reluctant Communist, Jenkins claimed that none of them ever actually believed in what they were taught. Dresnok displays complete allegiance to his adopted country in the 2006 documentary Crossing the Line, but he was likely reading a prepared statement, as is customary for DPRK media appearances.

The four Americans had limited value for Korean state propaganda. They initially attempted to use the men as English teachers, but their heavy Southern accents and lack of education proved insurmountable barriers. The most notable was their appearance as evil American villains in the 1978 North Korean film series Unsung Heroes, released the same year Kim Il-sung’s son and successor Kim Jong-il abducted South Korean filmmaker Shin Sang-ok and his estranged actress wife Choi Eun-hee in hopes of bringing new life to staid DPRK movies.

The Americans became overnight celebrities in North Korea — with audiences affectionately referring to Dresnok by his character name “Arthur” — and, to cement their place in the DPRK, the men were introduced to foreign women who would become their wives. During the 1970s, Pyongyang was notorious for abducting foreign nationals or tricking them into traveling to the DPRK. Jenkins’s wife Hitomi Soga was one of the dozens abducted along the Japanese coast by North Korean spies. Dresnok married a Romanian woman named Doina Bumbea who had also been kidnapped, while Parrish and Abshier wed Lebanese and Thai abductees, respectively. The hope seems to have been that their children would be racially ambiguous spies, loyal to their country of birth and fully indoctrinated into the system.

Until 2002, the only information about the defectors was Unsung Heroes (which the US government acquired in 1996, as proof they had survived). However, Japanese prime minister Junichiro Koizumi brokered a summit with Kim Jong-il that year in which Kim acknowledged that North Korea had abducted Japanese nationals, allowing five of them including Hitomi Soga to return to Japan. The uproar was immediate, and Tokyo put intense pressure on Pyongyang to reveal more information about who had been abducted, who was dead and who was still alive.

By this point, Abshier and Parrish had both died of natural causes, leaving only Jenkins and Dresnok. The two men had a complicated relationship, friendly some years and hostile others. While Dresnok had spent his whole life hoping to have a stable family and was growing content with life in North Korea, Jenkins and his two daughters were desperate to be back with Soga, who had chosen to stay in Japan.

After a couple of years of negotiations, the family were reunited in Indonesia and later relocated to Soga’s hometown of Sado Island. Jenkins had spent nearly forty years in North Korea and his subsequent court-martial proceedings for desertion attracted intense media coverage. Ultimately, he only served twenty-five days in the brig. Many in America called Jenkins a traitor, but his reception in Japan was more sympathetic, not least because of the valuable information he provided authorities about other Japanese nationals abducted by North Korea.

I met Jenkins on August 28, 2017 while visiting Sado Island. Well accustomed to life in Japan, he was working as an employee of the island’s history museum, posing for pictures with tourists and selling them senbei rice crackers. It is often said that living in North Korea for many years can rapidly age a person due to the stressful conditions and abundance of cigarettes and alcohol to pass the time. While Jenkins looked better than he did upon his repatriation in 2004, his tired expression and many wrinkles were reminders that most of his adult life had been spent in the DPRK.

Though a bit sheepish at first, he slowly opened up as I stuck around to talk with him. His North Carolina drawl was stronger than ever — amusingly, he claimed that he was more comfortable speaking Korean than English. He reaffirmed much of what he had already stated in his book, and it seemed that he still considered the other Americans his friends, even Dresnok, who DPRK state media reports claimed had passed away the previous year. Of them all, Jenkins was the only one to have left North Korea and lived to tell his story to the world.

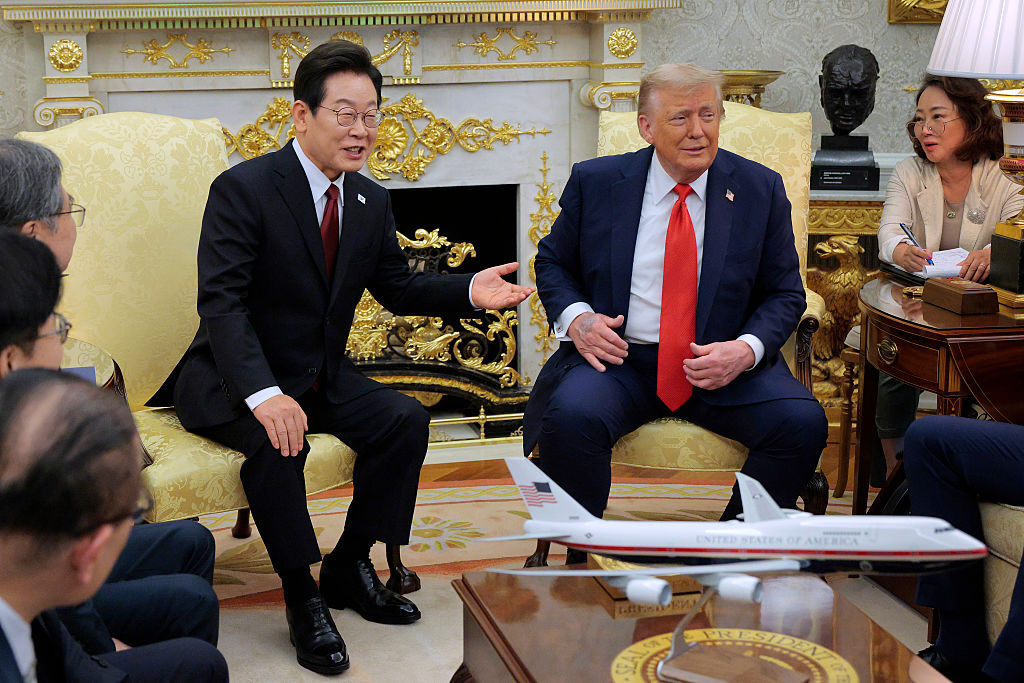

This was at the height of 2017’s volatile “fire and fury” rhetoric when Donald Trump and present DPRK head Kim Jong-un traded insults for much of the year. Jenkins expressed doubts to me that Trump would even finish his first term and believed that direct military confrontation would be the only way for North Korea to change. Less than four months after our meeting, he passed away at seventy-seven due to cardiovascular disease, likely the final result of many years of poor health in North Korea.

As for other US soldiers who went to the DPRK, Roy Chung, a Korean American, defected from West Germany in 1979, while Joseph T. White followed in 1982. Little is known about Chung (not even Jenkins had heard of him when I asked), while White was reportedly kept separate from the other Americans. As usual, Pyongyang claimed that White had defected for ideological reasons, but those who knew him claimed that he had shown no prior interest in communism. His death is also a point of contention. State media later reported that White drowned while swimming in a river, while Jenkins wrote that he suffered from an epileptic seizure. Jenkins also alleges that Seoul City Sue was executed in 1969 on charges of being a double agent for South Korea, but his claims cannot be independently verified.

With the apparently quixotic exception of Travis King last year, defection to North Korea has all but ended. The Cold War ended the viability of communism (and its few US adherents are unlikely to join the military), and the internet has somewhat lifted the veil of ignorance surrounding North Korea. The abduction and death of American student Otto Warmbier in 2017 reminded Americans who might have forgotten just how rigid and implacable the DPRK’s regime can be. Early in 2023, a 2019 YouTube video from travel vlogger Simon Wilson went viral on social media, featuring one of Pyongyang’s water parks and praising its cleanliness and modern features. The people looked healthy and happy, but nobody bought it. For North Korea, the propaganda doesn’t really work anymore.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply