This week Donald Trump declared “Liberation Day,” unveiling a barrage of tariffs that had been trailed as correcting for unfair trade practices overseas. In a theatrical Rose Garden ceremony, he presented a table, detailing a slew of new “reciprocal” tariffs targeting nations right across the globe.

Traditionally, trade reciprocity implies matching another country’s tariffs tit-for-tat. For instance, if the UK imposes a 10 percent tax on US chicken, the US would impose the same import tax on British chicken. Many had anticipated that “Liberation Day” would therefore introduce a complex array of tariffs reflecting the barriers other individual nations place on importing specific American goods.

Trump’s instincts instead took him in a much weirder direction. The President views trade deficits themselves as evidence of other countries exploiting the US, regardless of their actual trade policies. In his eyes, the US importing more than it exports equates to “losing,” which he sees as synonymous with underlying non-tariff barriers to trade or currency manipulation from trade partners, even when they aren’t taxing American imports heavily.

President Trump’s new tariffs therefore focus on penalizing countries based on the trade deficits the US has with them, rather than addressing specific trade policies. The administration calculates its proposed tariffs using a formula: they take the trade surplus the partner country in question runs with the US, divide it by the total imports from America, and then halve the result to determine America’s retaliatory tariff rate. This approach effectively punishes nations if American consumers purchase more of their foreign goods than the foreign country’s consumers buy from the US.

Given its substantial goods surplus with the US, China now faces an additional 34 percent tariff on top of existing duties, for example. But Trump’s approach isn’t limited to targeting geopolitical rivals; allies are in the crosshairs too. Japan is hit with a 24 percent “reciprocal” tariff, India 26 percent, and Vietnam a hefty 46 percent, all due to them importing fewer American goods than they export to the US.

Nor has the UK escaped. Mercifully for Keir Starmer’s government, America’s statistical agencies think the US runs a goods surplus with Britain. Does this not, by Trump’s own logic, mean the US is taking advantage of the UK? Consistent logic would say so, but Trump doesn’t see it that way. Even for countries that America runs a trade in goods surplus with, like Britain, Trump has slapped on a minimum 10 percent tariff for good measure.

This trade deficit-correcting approach leads to bizarre outcomes. Goods from famously protectionist nations like Brazil receive the same 10 percent minimum tariff rate as products from the notably free-trading Singapore, simply because the US runs a trade surplus with both. Even countries that the US has free-trade agreements with, like South Korea and Australia, are hit with the 10 percent rate too, despite those agreements eliminating most tariffs. Meanwhile, Israel, a US ally that dropped all its tariffs on American goods this week, faces a higher reciprocal tariff (17 percent) than Iran, a US adversary.

This approach is deeply confused. Ultimately, it’s based on an intellectual error. There’s no reason to expect balanced trade in goods between every pair of countries. If a country develops a unique product that America cannot produce – or it is not in America’s advantage to produce – consumers in the US will import it. This is good for Americans. It also, in isolation, creates a trade imbalance.

President Trump seems to think this is a problem. But bilateral trade balances in goods are influenced by various factors, including technological advancements and consumer preferences. Some foreigners might not want to buy an equal value of American goods. Instead they want to invest the money into American assets or buy American services (the latter of which Trump kept out of the tariff calculations). Headline “deficits” don’t tell us anything about the existence of unfair trade practices, let alone whether economic harm is involved.

True, old-school mercantilists wrongly believed national wealth came from stockpiling gold and silver, so requiring promotion of export surpluses. Their intellectual heirs today tend to fixate on a country’s overall trade deficit with the rest of the world, usually arguing that a large and persistent deficit can sometimes reflect unhealthy imbalances in global saving and investment flows.

Yet the logic of Trump’s thinking is much less coherent than even these positions. He doesn’t just worry about America’s overall trade deficit; he demands balanced trade with each and every individual country. Worse, his focus on goods trade means he completely ignores America’s large and growing trade surplus in services – giving a highly distorted assessment of America’s overall trade position.

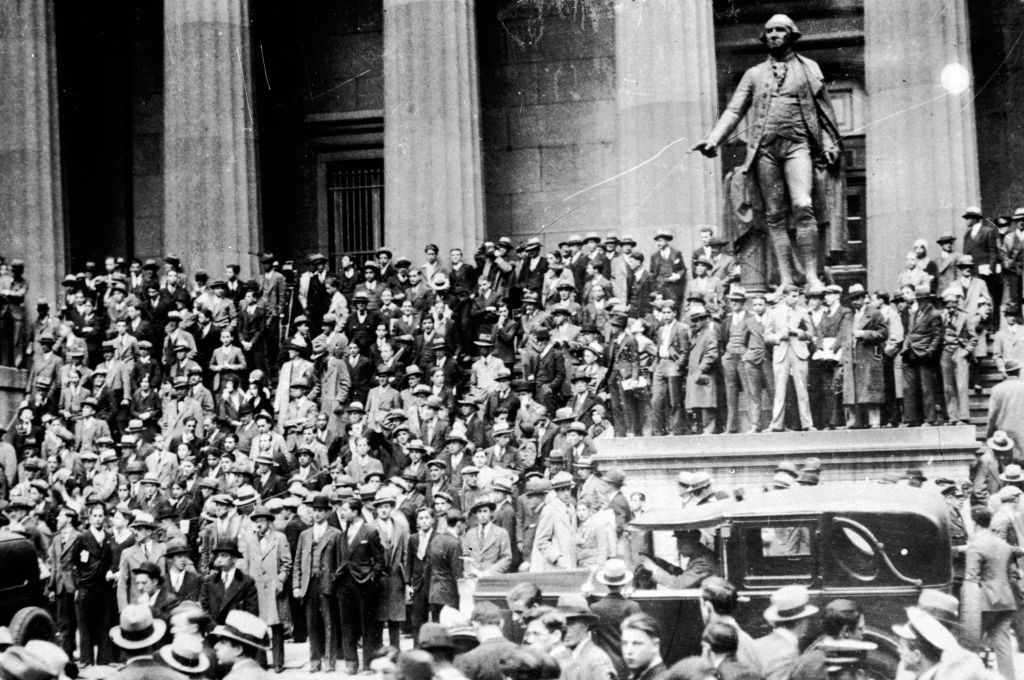

The result, in this case, is a raft of extremely high new tariffs that will hugely disrupt global trade flows, while throwing supply chains and investment decisions into chaos. Sadly, the economic case against this self-harm has fallen on deaf ears, with a President who has been consistently hostile to trade deficits and who now doesn’t have to worry about re-election.

The only remaining ways to avoid wanton economic destruction are Congress reclaiming its authority for trade policy or a sharp market reaction that leads to a change of heart in the White House.

Leave a Reply